Introduction

Liberalism is not one doctrine, but a family of them. In Michael Freeden’s very good Liberalism: A Very Short Introduction (2015), he rightly implores us to recognize the existence of ‘many liberalisms’ that are all committed to a core set of ideas but which disagree on how to interpret even these and can sometimes break sharply over issues on the peripheral range of settled liberal ideology. Put simply, much like we often find ourselves wondering how we are related to the oddballs in our family, not all liberalisms think alike or get along. As Alan Ryan notes in The Making of Modern Liberalism (2012), any over-ambitious analyst who wants

to give a brief account of liberalism is immediately faced with an embarrassing question: are we dealing with liberalism or with liberalisms? It is easy to list famous liberals; it is harder to say what they have in common. John Locke, Adam Smith, Montesquieu, Thomas Jefferson, John Stuart Mill, Lord Acton, T.H Green, John Dewey, and contemporaries such as Isaiah Berlin and John Rawls are certainly liberals—but they do not agree about the boundaries of toleration, the legitimacy of the welfare state, and the virtues of democracy, to take three rather central political issues.

Bringing light to these issues is no longer just a matter of intellectual clarification. Liberalism, in whatever flavour, is without a doubt facing a crisis. Failing to recognize the important role of liberalism’s reactionary enemies in generating this crisis would be ideologically narcissistic. But as I’ll argue here, much of the crisis was of liberalism’s own making. The failure to offer a liberalism of hope to citizens by retreating defensively into a liberalism of fear was, ironically, a poor defensive decision that has left us vulnerable to longstanding criticisms which resonate deeply with the general public. If liberals don’t engage in genuine soul-searching about our failures it is very possible liberalism will not survive. Worse, it is very possible that many people will not miss it.

A Liberalism of Hope

During the Cold War, a major effort was made to present liberalism as a moderate, cautious, and distinctly anti-utopian creed. Without a doubt, per Ryan and Freeden, there are undoubtedly elements of liberalism that suggest such an interpretation. But as recent historians like Samuel Moyn in Liberalism Against Itself (2023) have pointed out, this ignores the extent to which liberalism emerged as a fighting and revolutionary creed.

In the seventeenth century, the British Isles were rocked by multiple civil wars. Conservatives like Robert Filmer penned polemics arguing for the divinely ordained necessity of monarchical rule but were lampooned by Locke as opponents of freedom. It has long been popular to portray the American Founding Fathers as cautious Burkeans in their souls, launching a political rather than a social revolution. But as Sheldon Wolin argued in The Presence of the Past (1989), this ignores how the Founding Fathers were if anything revolutionaries twice over. They revolted against the monarchy abroad and expelled the ‘Tories’ at home to Canada, and then later abandoned the initial American constitution to draft an entirely new one. In continental Europe, the French revolutionaries undoubtedly committed enormous atrocities warranting fierce condemnation. But the Revolution and the successive agitation it unleashed just as undoubtedly spread liberal ideals of republicanism, the rights of man, and liberty, equality, and fraternity across the continent and beyond to colonies like Haiti.

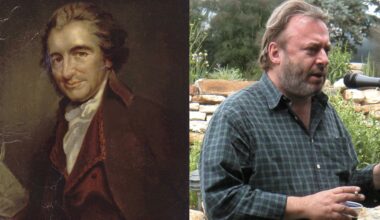

As Moyn stresses, these liberal revolutionaries were nothing if not ambitious. Before the quote was bastardized by Ronald Reagan, arch-revolutionary Thomas Paine’s insistence that we had it in our power to begin the world over again was intended as a repudiation of aristocratic hierarchy and the entire society on which it was built. Not coincidentally, the author of Rights of Man later expanded his critiques to the rich in general. Paine insisted that property was a social rather than natural institution and that the rich should be heavily taxed as a matter of right for expropriating land once held in common and so in effect dispossessing the poor. Mary Wollstonecraft, Olympe de Gouges, and others intimated that one day liberal principles and rights would even be extended to women, to the betterment of all.

Later, iconic liberals like John Stuart Mill in his Autobiography proudly declared themselves to fall ‘under the general designation of Socialists.’ By the mid to late nineteenth century, this attitude was far more common than is now appreciated. In her The Lost History of Liberalism (2018), Helena Rosenblatt notes that many

proponents of the new liberalism admitted that they could be seen as preaching socialism, but they didn’t mind. In 1893 a leading liberal weekly in Britain wrote that “if it be Socialism to have generous and hopeful sentiments with regard to the lot of those who work…we are all Socialists in that sense.”

What united these various progressive liberalisms was a distinct sense of hope for the future. It was felt that the normative extension of liberal principles and practices coupled with the further development of the natural sciences would enable liberals to carry on the project of undoing artificial and domineering hierarchies to build a society where the free and equal flourishing of all would become possible for the first time. And if it was possible, it was necessary. Today this liberalism of hope continues in the writings of those like Elizabeth Anderson who would see us extend liberal rights to the workplace and the economy as a whole for the sake of the least well-off, and in the activism of those who still think that liberalism carried the promise of justice for those long the victims of racism, sexism, and homophobia.

A Liberalism of Fear

Moyn points out that these optimistic and ambitious kinds of liberalism, liberalism(s) of hope, gave way to what he terms Cold War liberalism in the mid-twentieth century. Following his references to Judith Shklar, I will call these liberalism(s) of fear. The ascendance of totalitarianism in the twentieth century shocked and appalled many liberals. Fascism on the right and communism on the left came to be derided, and often very crudely conflated, as various species of collectivism committed to a closed society.

Many liberals became deeply spooked by what they considered the dangerous attraction of the masses to demagogic politics. Authors like Isaiah Berlin, Shklar, Karl Popper, and Friedrich Hayek—often drawing on conservative ideas from philosophers like the late Burke—insisted that the attraction of liberalism lay precisely in its realistic and narrow aspirations for politics. This in turn was rooted in a pessimistic conception of human nature as fundamentally competitive, often irrational if not constrained by conservative forms of spontaneous order, and given to dangerous outbursts of aspiration. Often the liberalism of fear was coupled with a distinct concern about the excesses of democracy—a concern that is echoed today when liberals talk about the ‘ignorant masses’. Hayek’s insistence that a liberal dictatorship is preferable to a socialist democracy is emblematic.

Paradoxically, these liberalisms of fear could often be driven towards their own kinds of radicalness in the name of securing property rights. Consider the immense neoliberal efforts to restructure the global economy to, in the words of economic historian Quinn Slobodian in Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism (2018), ‘encase’ capitalism from democratic pressures. But by and large, liberals came to be associated with a kind of technocratic and cautious elitism, highly educated and removed from a general public that just couldn’t appreciate that Hillary Clinton was the best qualified presidential candidate in our lifetimes.

The Failure of Liberalisms of Fear

Ironically the decision to embrace a liberalism of fear was a very dangerous one—for liberals. In his epic work Civil Religion (2010), Ronald Beiner notes that liberalism has always been vulnerable, above all, to the reactionary critique that it is a philosophy fit only for the banal. As Beiner notes, arguably the ‘deepest objection to liberalism as a way of life is its deliberately nonheroic or anti-heroic attitude to life, its banalization of the problem of human existence…’

Beiner himself notes that these right-wing critiques forget that liberalism can indeed be heroic, as when it started revolts against clerical power. And, I would add, in its fights against monarchy, aristocracy, sexism, and—at its best—poverty and racism. But the liberalism of fear to which liberals turned in the twentieth century vindicated this right-wing objection to a spectacular degree and left liberals very open to accusations by populists from Trump to Orbán that they were out of touch, low energy, nebbish, and weak.

Until liberals decide it is time to abandon the cautious attitude of the liberalism of fear, these accusations will not go away and they will continue to stick. And they’ll continue to stick because they are deserved. But it needn’t be so. Liberalism has triumphed over dangerous enemies before, and we can succeed again. But not by doubling down on the most consciously uninspiring forms of liberalism—i.e. desperately chasing after the Matt Yglesias vote.

What is needed is a liberalism of hope that is unafraid to confront deepening oligarchy and call it what it is: just the latest aristocracy erected by those who deny that we are all equal and deserve to be treated with equal dignity. People deserve better than that, and a liberalism of hope can deliver it to them. Perhaps such a liberalism would even deserve once more to be called heroic.

Related reading

Books from Bob’s Library #2: Thomas Paine’s ‘Rights of Man’, by Bob Forder (See also the full Books From Bob’s Library series here)

The rhythm of Tom Paine’s bones, by Eoin Carter

Introducing ‘Paine: A Fantastical Visual Biography’, by Polyp, by Paul Fitzgerald

American democracy will soon turn 250. Freethought can reinvigorate it. By Patrick Seamus McGhee

The radical atheism of the American revolutions: interview with Matthew Stewart, by Daniel James Sharp

Image of the week: ‘The world is my country, to do good my religion!’, by Bob Forder

Defending liberalism: interview with Helen Pluckrose, by Daniel James Sharp

Confronting identity politics, a breeding ground for division and dehumanisation, by Maryam Namazie

The Marketplace of Ideas will always exist. The only choice we have is how to work with it. By Helen Pluckrose

Humanists and ethical reform in mid-twentieth-century Britain, by Charlie Lynch

‘We need to move from identity politics to a politics of solidarity’ – interview with Pragna Patel, by Emma Park

Image of the week: ‘The Tree of Liberty – with the Devil tempting John Bull’ by James Gillray (1798), by Bob Forder

How three media revolutions transformed the history of atheism, by Nathan Alexander

The Enlightenment and the making of modernity, by Piers Benn

Milton’s ‘Areopagitica’: liberty and licensing, by Tony Howe

Bring on the British republic – Graham Smith’s ‘Abolish the Monarchy’, reviewed, by Daniel James Sharp

‘I do not think you are going to get a secular state without getting rid of the monarchy’: interview with Graham Smith, by Daniel James Sharp

Christopher Hitchens and the long afterlife of Thomas Paine, by Daniel James Sharp

What’s Happened to Free Speech? Musings of a Troubled Freethinker, by Bob Forder

Charles Bradlaugh and George Jacob Holyoake: their contrasting reputations as Secularists and Radicals, by Edward Royle

Meaningful Control: The Pursuit of True Economic and Political Democracy, by Zwan Mahmod

Donald Trump is an existential threat to American democracy, by Jonathan Church

Donald Trump, political violence, and the future of America, by Daniel James Sharp

Can the ‘New Theists’ save the West? by Matt Johnson

Do we need God to defend civilisation? by Adam Wakeling

The Enlightenment paradox: review of ‘Dark Brilliance’ by Paul Strathern, by Adam Wakeling

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate