There is an important error to be found in chapter eight of my History of Atheism in Britain (1988), the exposure of which I owe to A. J. Ayer who wrote in a review of that book: ‘I am reluctant to criticize Berman, since I have derived so much information from his book, but I deplore his failure to remark that the logical fallacy of attempting to found morals on religion was already exposed by Plato.’ (New Humanist, 1988, p. 31.)

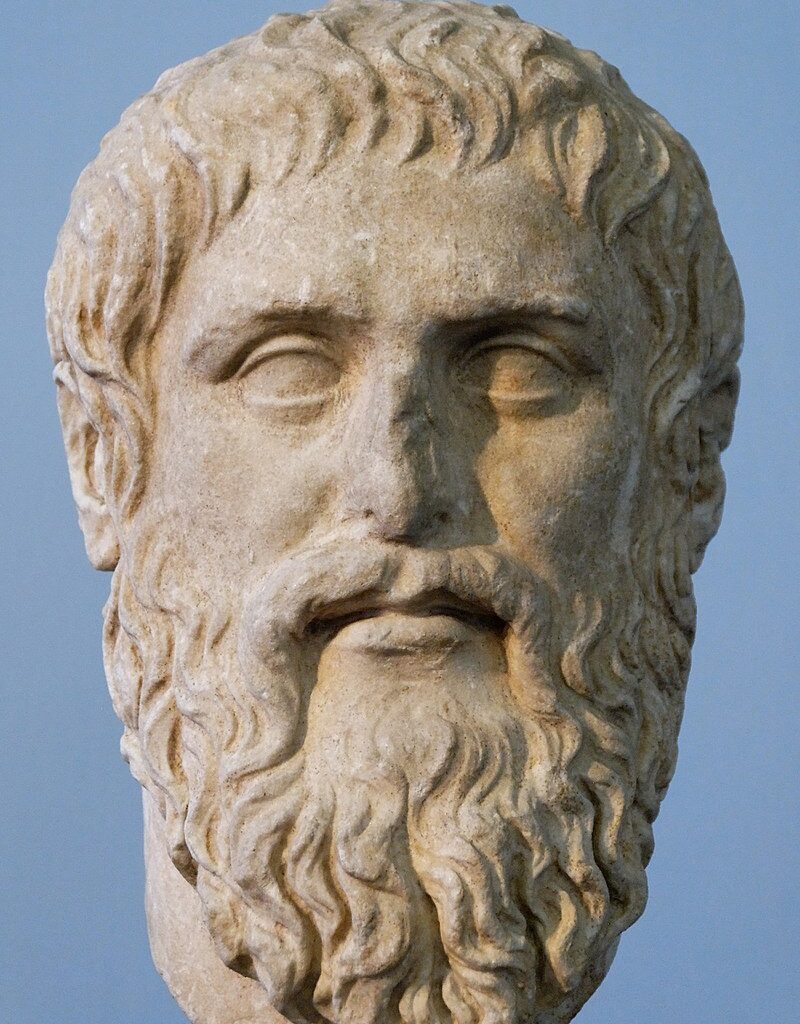

The logical fallacy is to be found in Plato’s Euthyphro, for which reason it is generally known as the Euthyphro Dilemma. In short, moral values are valuable either independently of God (and thus God loves them) or because God made them and loves them. Ayer takes the former as the only feasible option, since, as he observes, to say that God’s decrees are good is not a tautology; hence it follows that goodness is logically independent of God’s decrees.

Now, though it is nearly 40 years since Ayer’s review of my History appeared, I think his criticism stayed in my mind and has helped me to see what is importantly wrong in my account of Locke and especially Berkeley in chapter eight of the book. And not only did I not see it then, but it has taken me a long time to see it clearly. Hence, I think it would be helpful to others if I say a word more about it here. For while the Euthyphro Dilemma seems clear such that one either believes that (1) God creates moral values or (2) He does not create them, for they exist either co-eternally with Him, or independent of Him, what I did not see was that philosophers such as Locke and Berkeley had a middle way in which they could soften the either-or and not accept (1). But while this is not entirely clear from their texts, it becomes so if one sees the middle way.

To begin, then, with Berkeley’s major work on ethics, namely his Discourse on Passive Obedience (1712), Berkeley says that ‘nothing is a [moral] law merely because it conduceth to the public good, but because it is decreed by the will of God’. From this I thought it was clear that Berkeley did go for option (1), but what he immediately says after should have raised a doubt in my mind: ‘which alone can give the sanction of a law of nature to any precept’. For this suggests that what Berkeley was referring to was God’s enforcing power, not His power to create what is good.

This is even clearer in what Locke says in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689), II.28.8, where Locke too begins in a way that suggests he goes for option (1): ‘the divine law… [that] God has given a rule whereby men should govern themselves, I think there is nobody so brutish as to deny.’ But once again, what Locke goes on to say should raise a question for the careful reader, especially his use of the words ‘right’ and ‘goodness’: ‘[God] has a right to do it; we are his creatures: he has goodness and wisdom to direct our actions to that which is best…’. From this it follows that Locke must surely have believed that moral values exist prior to or eternally with God, and this is strongly supported in his ‘Epistle to the Reader’ in the Essay’s sixth edition where Locke speaks of the ‘eternal and unalterable nature of right and wrong’. So at the least, Locke thinks that God does not create right and wrong and that they are co-eternal with Him.

In short, when I wrote my History, I thought that Locke and especially Berkeley were saying that without God, there would be no moral values. What they actually meant was that without God, moral values would not be feasible in a practical way. For who would bother obeying moral values if there were no practical consequences for not doing so? What Locke and Berkeley were asserting is not that there is no morality without religion, but that without otherworldly rewards and punishments, morality would not motivate our actions. (The validity of all these arguments is, of course, another matter entirely.)

Hence it turns out that John Milton is the only writer whom I quote in my History who clearly did go for option (1), for in his On Christian Doctrine (which was not published until 1825 and whose authenticity has been debated, though it is generally accepted that it is at least partly Milton’s work) he says that ‘If there were no God, there would be no distinction between right and wrong’.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate