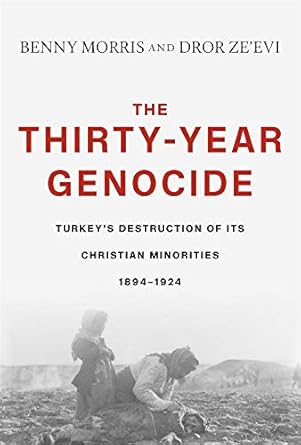

The sheer scale of the systemic crimes and horror unleashed by the Ottoman Empire in its twilight years is unfathomable. The destruction of the Armenians, Assyrians, and Greeks between 1894 and 1924 was not a series of isolated massacres, nor the unfortunate consequence of wartime chaos, but a deliberate, calculated campaign of extermination, forced conversion, and national erasure. Such is the convincing argument put forward in Benny Morris and Dror Ze’evi’s 2019 book The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey’s Destruction of Its Christian Minorities, 1894–1924. Yet, more than a century later, Turkey has not only evaded justice but has actively rewritten history to bury its monstrous past. Why has this nation, built upon the bones of the indigenous Christian peoples of Anatolia, never been held to account? Why does the world turn a blind eye to the crimes of Islamic imperialism and colonialism when, in every other instance, it clamours for truth and reconciliation?

One of Morris and Ze’evi’s most damning revelations is the role of forced Islamisation during these terrible years. Western portrayals too often depict genocide as solely a physical slaughter, but The Thirty-Year Genocide forces readers to recognise the insidiousness of cultural erasure. The Ottoman Caliphate’s genocidal project was as much about the conquest of the mind as it was about the conquest of the land. The Armenians, Assyrians, and Greeks—civilisations predating the arrival of the Turkic tribes in Anatolia by millennia—were not merely slaughtered; their languages, churches, histories, and identities were systematically erased. Survivors were given a choice: convert to Islam or die. Women and children were abducted and forced into Turkish households, assimilated into an alien identity under the guise of Islamic charity. It was an extermination not only of bodies but of entire cultures, a totalising war against existence itself.

As Morris and Ze’evi meticulously document, these atrocities were not limited to the infamous events of 1915. The massacres of the 1890s under Sultan Abdul Hamid II, the bloodbaths during the Young Turk era, and the final cleansing under Atatürk all followed the same logic: the systematic destruction of Christian communities. The evidence is overwhelming. Ottoman officials kept records of forced conversions, calculating the percentage of the Armenian, Assyrian, and Greek populations that had been successfully ‘assimilated’. In some cases, entire villages were herded into churches and burned alive—echoing the tactics of later totalitarian regimes. And then there were the infamous death marches: men, women, and children driven into the Syrian desert without food or water, subjected to unspeakable cruelty by Ottoman soldiers.

And yet, the world remained silent. Why did the great powers, who so often wield the sword of justice against historical wrongs, fail to bring Turkey to task? Why do they still turn a blind eye to this historical crime? The answer lies in the cold calculus of realpolitik. Turkey, straddling East and West, a gatekeeper to the Middle East and now a lynchpin in NATO, enjoys a strategic position that has bought its immunity. Organisations, politicians, and countries that lecture the world on moral responsibility conveniently forget the genocides of the Ottoman Empire when economic and military interests are at stake. Western governments fall over themselves to appease Ankara, fearful of jeopardising trade deals or military alliances.

This moral cowardice is compounded by the myth of Atatürk’s ‘modern’ Turkey. The Republic of Turkey, founded in 1923, did not emerge from the ruins of the Ottoman Empire as a break from its imperial past; it was its natural successor, inheriting its territories, institutions, and, most crucially, its ethos of denial. The same officers who orchestrated the Armenian Genocide seamlessly transitioned into leadership roles in the new republic. The nationalist rhetoric of the Young Turks, which justified the extermination of Christians, found a new lease of life under Atatürk, who continued the project of Turkification with ruthless efficiency. The continued persecution of remaining minorities, the erasure of their cultural heritage, and the official rewriting of history were all part of the same campaign. The Thirty-Year Genocide shows that Atatürk’s Turkey actually went even further, criminalising any discussion of the genocide and systematically eliminating remaining Christian villages. How can a nation founded on genocide acknowledge its original sin without undermining its very existence?

Legal and diplomatic efforts to hold Turkey accountable have been hampered by the simple passage of time. Under international law, state responsibility for crimes against humanity is rarely retroactive, and Turkey has wielded this technicality as a shield. The Armenian Genocide was the precursor to the Holocaust, inspiring the very term ‘genocide’ itself, yet no Nuremberg-like trials were ever held for its perpetrators. Why? Because the victors of World War I lacked the political will to implement justice, and by the time the world was ready to confront genocide as a legal concept, Turkey had already secured its position as an indispensable player in global geopolitics.

Complicity extends beyond governments. The academic world, so often quick to dissect and condemn the sins of European colonialism, has remained conspicuously silent on the crimes of Islamic imperialism. Where are the university courses on the destruction of Anatolia’s Christian civilisations? Where are the museum exhibits, the films, the cultural reckonings? The same intellectual class that demands decolonisation in every Western institution has nothing to say about the forced Islamisation and Turkification of entire peoples. The erasure of Christian Anatolia was not just a historical event—it was a process that continues to this day, reinforced by state censorship, propaganda, and the systematic persecution of those who dare to speak the truth.

Recognition of these crimes is not just about historical justice; it is about challenging the ideological double standards that dominate global discourse. The world has rightly condemned the genocides of Rwanda, Bosnia, and, of course, the Holocaust—why, then, does Turkey escape scrutiny? The crimes of the Ottoman Empire were not mere relics of a distant past. They set a precedent for modern authoritarianism, for the weaponisation of history, and for the impunity with which revisionists can rewrite reality, especially when the apparatus of the state is complicit in that rewriting.

And, of course, the cultural erasure is ongoing today. Erdoğan’s Turkey, with its increasingly assertive nationalist form of Islamism and ‘neo-Ottomanism’, is unlikely to be held to account, let alone make amends. If Turkey is never held accountable, what message does that send to other regimes with genocidal ambitions? That, with enough political leverage, history itself can be erased? And one must ask: when Islam is involved, does genocide get a free pass from the Western intelligentsia?

The breaking of the silence is overdue. It is time for the world to demand accountability for the annihilation of Anatolia’s indigenous peoples because of their Christianity. This is not about vengeance; it is about truth over narrative. Without recognition, without civil justice, those crimes in history stand still. They remain present. If we refuse to properly confront the crimes of the past, we will inevitably be complicit in the crimes of the future.

Related reading

Russian history, Russian myths: review of ‘The Story of Russia’ by Orlando Figes, by Mathew Giagnorio

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate