I first encountered Eliza Flower (1803-46) in an online search for women composers from Essex during the 2020 lockdowns. My search was part of a ‘Women in Music and Science’ project with Chelmsford Theatre, called ‘Echoes from Essex’. I found only one piece of a capella choral music, ‘Now Pray We for our Country’, but it was exactly what I needed for the project. It was by a composer called Eliza Flower, whom I had never come across before. In the spirit of those strange times, we made a virtual recording of it: the choir consisted of just six members of our Electric Voice Theatre singers, who recorded several parts each in their homes and sent them to us for assembly. The result of this early foray into virtual singing transformed what had been an intriguing score into a moving hymn with qualities quite unlike any I had heard from this era. (Recording by Electric Voice Theatre here.)

Here was something quite remarkable: a piece of sacred English choral music written in the 1820’s which displayed many of the traits of secular European romanticism. The latter movement would not become widespread in the UK for some time – at least not among male composers. Flower called for sharply contrasting dynamics and tempi. The rich and dramatic harmony she deployed, coupled with her use of contrasting chorus and soloist ensembles, suggested that this work was written for no ordinary church choir.

This was just one hymn. However, as I would discover later from a letter written by Eliza herself to Novello, it was a hymn that Felix Mendelssohn was ‘most pleased’ with.

Where had all these ideas, packed into one short piece, come from? Was there more? There had to be more!

The words Flower had set to music, although adapted from those of an American preacher, were patriotic and almost jingoistic in their fervour towards England. They were almost patriotic enough to have deterred this fervent Scot from looking further – but the quality and innovation of the music kept nagging at me. I was impatient to discover more.

We were, however, still locked in: a feeling that was, I suspect, familiar to many women in England during Eliza’s lifetime, who were either hemmed in by societies’ expectations or forced to work, and legally dependent on their male relatives, with no prospect of freedom.

In time, I would discover that Eliza was not constrained in these ways, but was set on a different path. Unlike most women of her time, she was encouraged and educated by her radical parents to think for herself and to seek to fulfil her potential. My initial idea of her, constrained in a drawing room, encased in stays and stiff brocades, would turn out to be far from the truth.

Once normal life resumed in 2022, I investigated further at the British Library in London. There was more music!

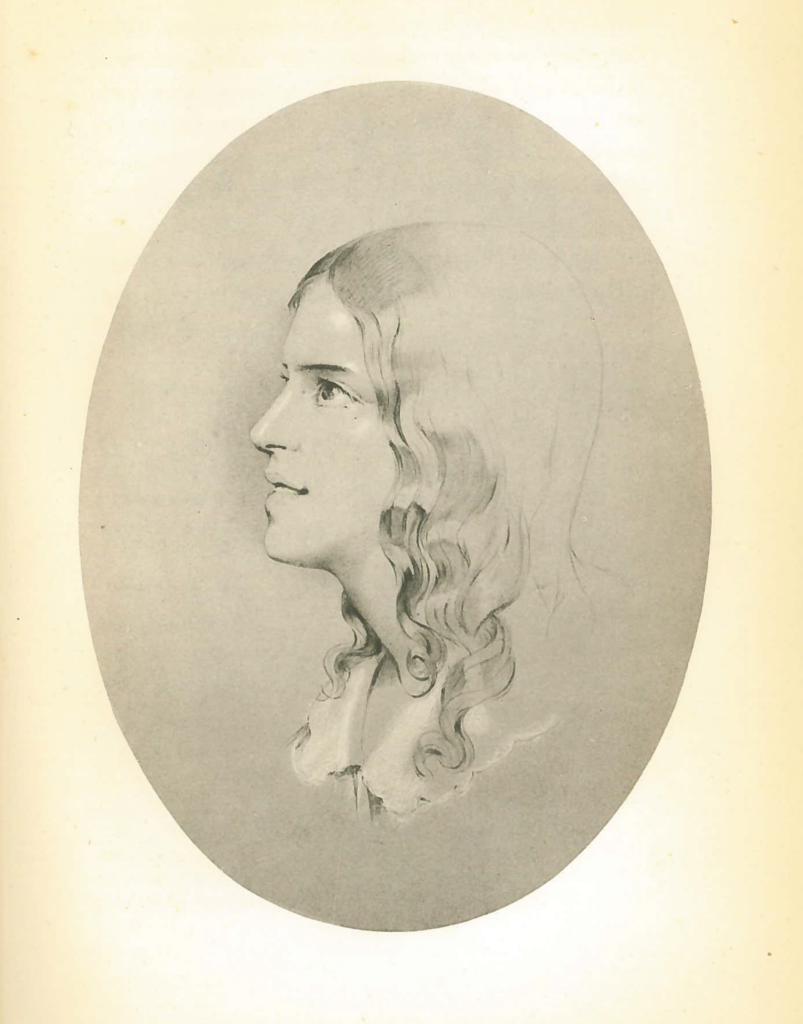

The staff handed me a published pot-pourri of Flower’s vocal music, a large manuscript book bound with others from the same period. As I opened it, I was taken aback by the full-page drawing of Eliza. She certainly did not have the look of a starched Victorian lady, but instead of a gentle, bohemian soul, with her hair in soft curls on her shoulders and a face which shone with love. The artist, Eliza Bridell-Fox, had made the portrait in recollection of the composer after her death. Little did I know how important these names would be to Eliza Flower’s story in different ways.

On the opposite page was the index, which pointed to 182 pages of music. This page was full of clues to Flower’s character and outlook on life, but at this point I just wanted to read the music and listen to it in my head – since singing out loud in the British Library Reading Rooms is unfortunately not permitted. I could not take it all away with me, but I copied as much as I could and, when I returned home, began to sing and play the music, and to share it with my colleagues in Electric Voice Theatre. This was the beginning of an adventure that would lead us to Conway Hall in London, and to a performance based on that index page and the variety of work that it represented.

As I explored the music, I found unexpected harmony and structures; wonderful melodies, hymns, songs and ballads; and a strong and clear voice for the rights of men and women at all levels of society.

But who was this woman, creating music at one minute for Christian services, at another for the salon, and at the next for workers protesting in the street?

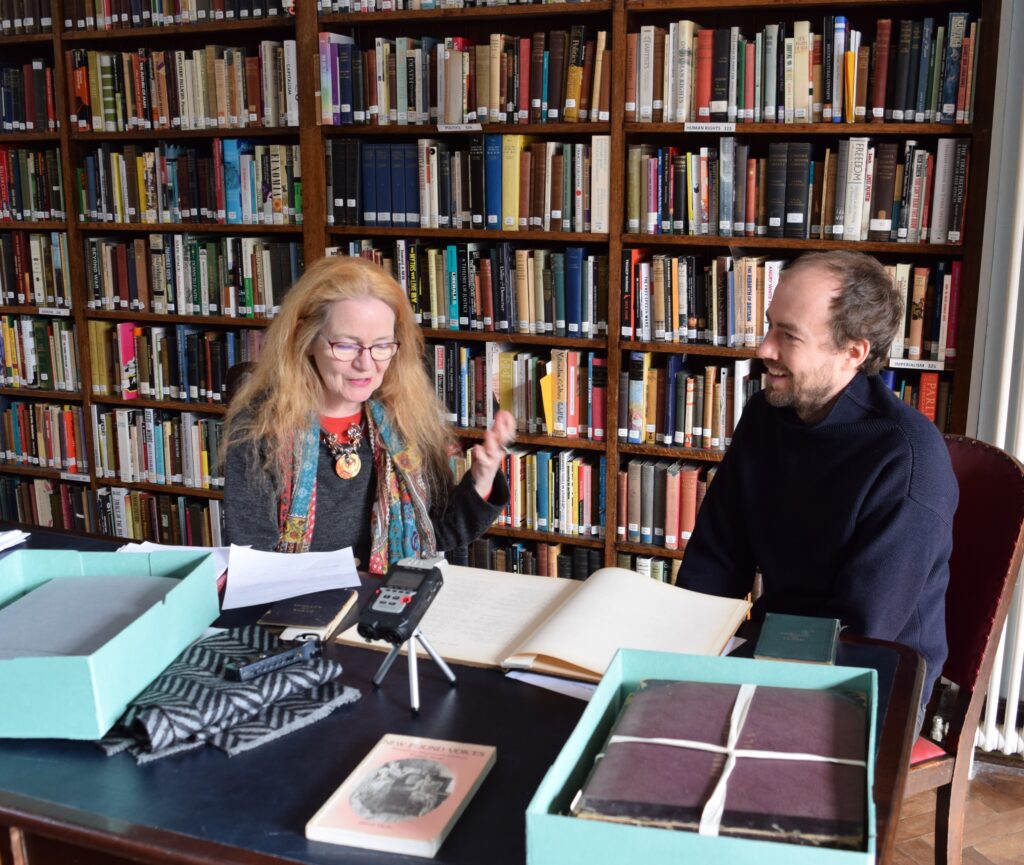

Thanks to the Conway Hall Ethical Society, at the invitation of Dr Jim Walsh, and to the efforts of researcher Carl Harrison and librarian Olwen Terris, my understanding of Flower’s music and ideas began to grow. When Holly Elson, Conway Hall’s Head of Programmes, introduced me to Oskar Jensen, a music historian, a new world opened up.

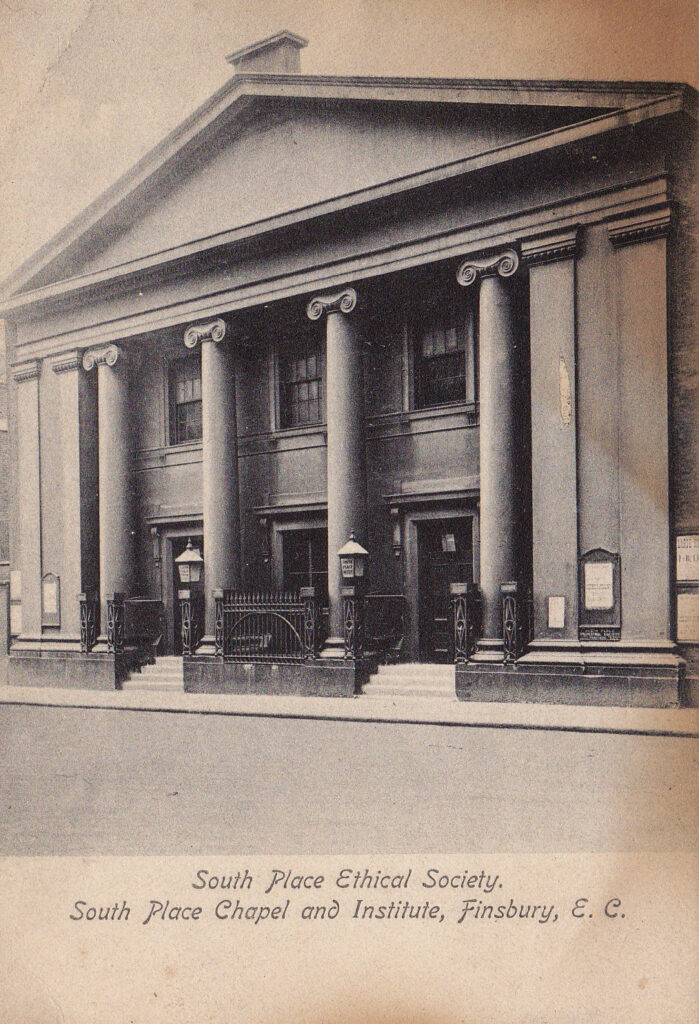

Oskar’s wide knowledge of Flower and of the musical and political history of the nineteenth century began to fill in some of the many gaps in her story. As we brought our own pieces of this fascinating jigsaw puzzle together, a fuller picture of Eliza Flower began to emerge as a highly regarded, prolific composer and radical feminist. Alongside her sister, the poet Sarah Flower Adams, she had exerted a profound influence on the move from Unitarianism at South Place Chapel in Finsbury towards humanism and the creation of the Conway Hall Ethical Society. The sisters’ contributions to the cultural and political life of the period were so important that when the chapel closed down, their portraits and archive were moved to Conway Hall, where they still hang in pride of place in the library, flanking a much bigger painting of the man usually credited with this move, William Johnson Fox. It seems this was, like so many other important historic events, a team effort. Yet gender bias eventually erased Eliza, and to some extent Sarah, from their shared history.

The beautiful drawing of Eliza discussed above holds the key to her story. When Eliza Fox, who became Mrs. Bridell-Fox and an artist, was only 11 years old, she was taken away from her mother by her father, William J. Fox, to live with him and Eliza Flower. They set up house together in the face of deep societal disapproval.

The courage this must have taken for Eliza to take up such a precarious position, totally reliant on Fox’s continued regard for her, can scarce be imagined.

Little Eliza Fox (the artist-to-be) went willingly to this new household. She loved and admired Eliza Flower, who, along with Flower’s sister, Sarah, had been part of the Fox household since their father’s death, with the then Reverend Fox as their guardian (after the break from his wife in 1834, he would eventually be removed from the Unitarian ministry). Reverend Fox, at the time minister of the congregation at the South Place Chapel, worked closely with Eliza Flower on his speeches, sermons and publications, and on the chapel’s political, spiritual, and musical direction. They grew closer, both spiritually and, apparently, in other ways, until in 1834 the break was made with Mrs Fox, who lost not only her husband, but her children too.

Not all of Fox’s congregation were happy about this arrangement, nor were some of the couple’s friends. For Eliza Flower, who by this time was a published and well-known composer, there was also the prospect that her music might be rejected by an outraged public. As a composer, her music fell into three distinct categories, each connected by her profound belief in equality and justice. I will now look at each of these categories in turn.

1. Sacred Choral Music

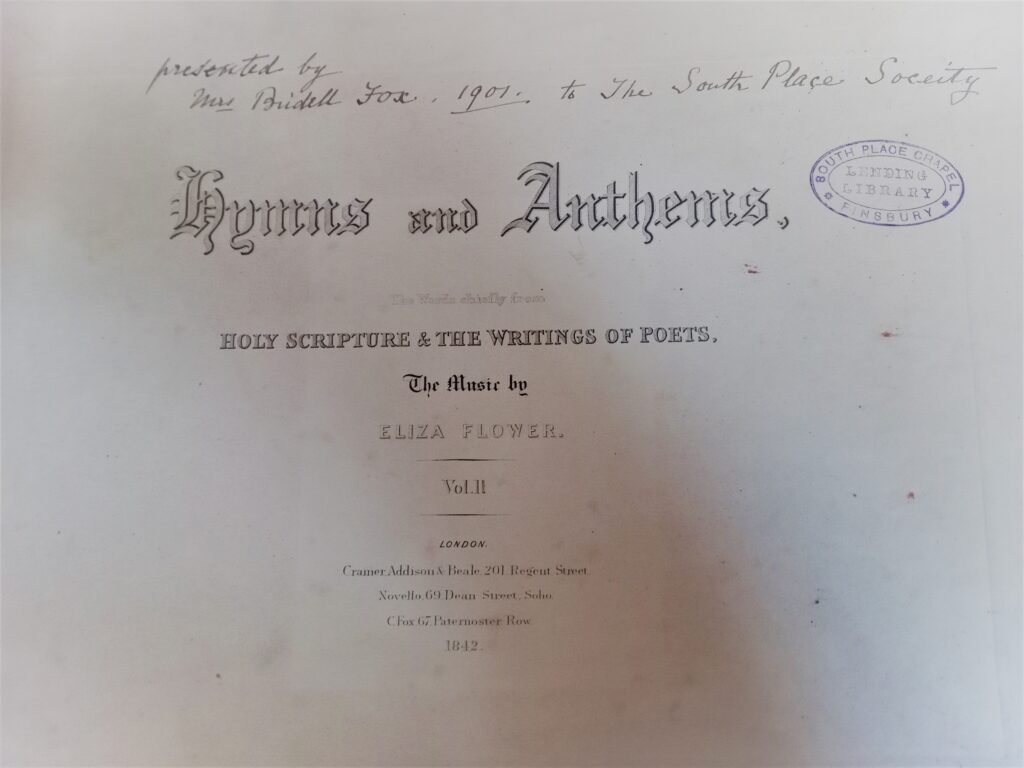

The hymn of Eliza’s that I first discovered turned out to be part of a book of ‘150 Hymns and Anthems’, published by Reverend Fox in 1841. Unusually, most are settings of poetry by the many freethinkers in Flower’s circle of friends – people like her sister Sarah (author of ‘Nearer, My God, To Thee’ with exquisite music by Eliza) and Harriet Martineau. These free thinkers expressed their ideas about morality with less emphasis on God than you might have imagined.

Take Hymn 139, ‘Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter’. Its lyrics are a poem by the Corn Law Rhymer Ebenezer Elliott (1781 – 1849), containing a moral that is still relevant today (recording here):

But Babylon and Memphis

Are letters traced in dust:

Read them, earth’s tyrants! Ponder well

The might in which ye trust!

…

They fell, because on fraud and force

Their corner-stones were founded.

Eliza’s setting has more in common with the drama of a Bach Passion or Handelian cantata than a hymn fit for congregational singing. As reported by South Place Magazine in September 1897,

‘South Place was at this time (1833) like other Unitarian chapels, until Miss Flower… commenced a reformation in the musical part of the services, which rivalled the attraction to the chapel of its excellent Minister. Miss Flower’s musical genius, knowledge, and feeling enabled her to exercise a kindly influence over the choir… which would not even have come into existence without her.’

Eliza was one of the first people to champion the move away from the use of music as part of a religious service in the Unitarian denomination towards secular chamber music, as she began to include art songs in her repertoire (see below). This legacy continues to this day in the Sunday Concerts at Conway Hall.

2. Art Songs

These beautiful songs often brush on the themes of love and nature, but some present a quite different approach.

Over 17 days in 1845, the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden held their extraordinary Bazaar. A musical score entitled ‘Free Trade Songs of the Seasons’, with music by Flower, was published by Novello to support the Anti-Corn-Law League at this event. The texts, by Flower’s sister Sarah, combine the familiar art song trope with the struggles of poverty-stricken labourers.

These songs were also intended for the drawing room, a place where ladies could pass on their clear message to their menfolk, who had the political power to change things. The Free Trade Songs were a very particular form of protest song, full of trills and turns, recitative, melismatic passages, harmonic surprises and strong melodic lines. The final Winter song moves in a choral march towards the last category of Flower’s work: the protest songs.

3. Protest Songs

Flower wrote many of these with Harriet Martineau, a feminist author and influential campaigner against slavery. Together, Martineau and Flower formed what Oskar Jensen has described as probably the most powerful protest-song partnership of the nineteenth century in the UK. Many of their songs became popular anthems, sung by thousands of protesting workers in the streets – most of whom would have had no idea that their voices were carrying the words and music of two young ladies.

William Fox, too, provided some of the texts, my favourite being ‘The Barons Bold, On Runnymede’, which, written in 1832, has the feel of a jolly Gilbert and Sullivan patter song avant la lettre. The words encourage us to ‘join hand in hand’ and stand up against the power of kings and state, so that ‘our wrongs shall soon be righted’.

Fox continued their work after Flower’s early death in 1846, but distanced himself from her memory. It is not clear why he did this, but it may have been partly in order to avoid scandal: he was intermittently a Member of Parliament between 1847-62. He stopped promoting Flower’s music, compounding the deeply ingrained bias faced by all female composers. This is demonstrated by research recently published by Donne, an organisation promoting women in music, which shows that 88 per cent of music played worldwide in major orchestral seasons is by dead white men. In the Victorian era, composition was seen as an abstract intellectual activity, more suitable for men than women. Eliza Flower was considered an exception during her lifetime. Unlike her contemporaries, Clara Schumann and Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel, she was not required to subvert her talent in favour of a musical husband or brother, but was free to express herself as a progressive composer, determined to leave her own musical mark. Yet this same memory was deliberately ignored after her death by the man to whom she had devoted her life. As John Stuart Mill wrote in a review of Flower’s music in 1831,

‘There are not only indications of genius as indisputable as could have been displayed in the highest works of art, but there is also a new ascent gained, a new prospect opened, in the art itself, which we welcome as a pledge of its keeping pace with the progress of society.’

As Robert Browning wrote to Eliza about her music, ‘I put it apart from all other English music I know, and fully believe in it as the music we all waited for.’

Yet like many women today, impostor syndrome loomed over Flower’s life. In a letter to Vincent Novello, she tells of her meeting with ‘Mendelssohn the grand, great as his music, as great an artist, (but not so good a man)’. Mr. Novello had encouraged her ‘to send those sacred songs to him, but I shrunk… They were however shewn to him – (not with my consent). His praise was worse than censure. I did not want opinion, but help. He said I had genius…’ However, Mendelssohn also implied that her musical ideas were irregular and would not be popular. Despite Mendelssohn, Flower was popular in her lifetime. With our project to revive her music, we hope she will be again.

Frances Lynch and the Electric Voice Theatre, together with Oskar Jensen, will be performing in Conway Hall’s historic library, Red Lion Square, London, at 19.00 on 27 October 2023. For more information and to book tickets, click here.

Enjoying the Freethinker? Subscribe to our free fortnightly newsletter for the latest updates on freethought.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate