Introduction

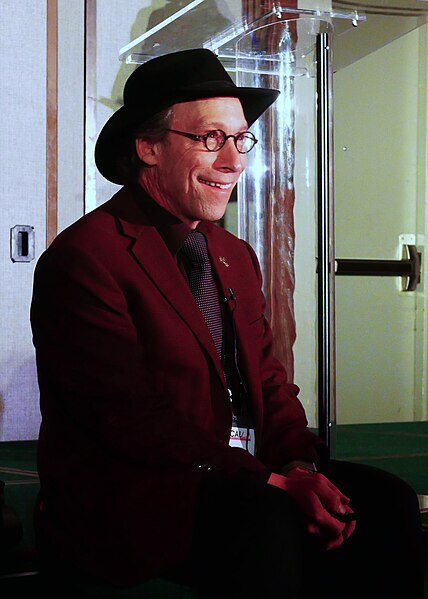

Lawrence Krauss is a Canadian-American physicist and writer who has published prolifically, both for an academic audience and for the general public. His books include The Physics of Star Trek (1995), A Universe from Nothing: Why There Is Something Rather Than Nothing (2012), The Greatest Story Ever Told—So Far: Why Are We Here? (2017), The Physics of Climate Change (2021), and, most recently, The Known Unknowns: The Unsolved Mysteries of the Cosmos (2023). He is currently president of The Origins Project Foundation and host of The Origins Podcast. For more information about these and other books by Krauss, see the relevant section of his website.

He is also known for championing science and rational thinking in public life and for a while was (in)famous as one of the so-called ‘New Atheists’ (on which more below). I recently spoke to him over Zoom to discuss his life, career, and opinions on religion and Critical Social Justice—or, more colloquially, ‘wokeism’.

Interview

Freethinker: How did your interest in science start?

Lawrence Krauss: I got interested in science as a young person, for a variety of reasons. At least, I can tell you what I think they were. First, I think it is important that my mother wanted me to be a doctor and my brother to be a lawyer. She had convinced me doctors were scientists, so I got interested in science. Plus, a neighbour who was an engineer and his son helped me build a model of the atom, which impressed me.

But it was reading books by and about scientists that really got me interested. I remember reading Galileo and the Magic Numbers (1958) by Sidney Rosen. I think I still have the book somewhere. It impressed on me the idea of Galileo as a heroic figure fighting the forces of ignorance and discovering strange new worlds.

And then I continued to keep reading books by scientists—Richard Feynman, George Gamow, and others—and I had science teachers who encouraged me, which I think is important.

I still was not certain if I wanted to be a scientist per se, because I liked a lot of other areas. Probably the most significant course that I took in high school was a Canadian history course, by far the most intellectually demanding of any of the courses I took. Later on, I took a year out of university to work on a history book about the Communist Party of Canada during the Depression, using my access to the archives of Toronto. I still have that box of files and I will write that book at some point.

I originally thought I wanted to be a doctor, specifically a neurosurgeon. I did not know what a neuroscientist was. Neither of my parents finished high school and my mother in particular just wanted us to be professionals. So I thought of becoming a neurosurgeon. I did not even know what a neurologist was, but the brain interested me. I remember getting a subscription when I was a kid to Psychology Today. I also remember getting a subscription to the Time Life Books on science, so every month for two years I got a book on different parts of science.

Why did physics in particular end up attracting your interest?

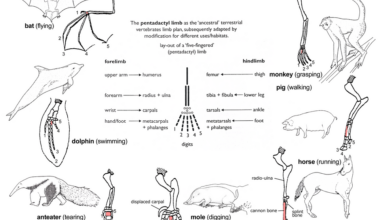

For some reason, like, I think, for many young people, physics seemed sexier in the sense of dealing with fundamental questions, the big, deep questions of existence. And although I was interested in biology, that interest evaporated when I took a biology course in high school and dropped it within two weeks because it was just memorising parts of a frog and dissecting things. I just found it totally boring and not what I thought of as science. That was in the 1960s, before the great DNA discoveries of the 1950s had filtered through to the high school level, and so I did not get to experience the explosion of biology as a scientific discipline at the time. I have tried to make up and learn since then, and I think if I had been more aware at the time, I might have been seduced by it.

But by that time I was already in love with physics. I felt the allure of physics and physicists like Feynman and Einstein. A book that had a lot of influence on me was Sir James Jeans’s Physics and Philosophy (1942), which I read in high school. That got me interested in philosophy for a while, too, and it took me a while to grow out of that! Later on, I nearly took a Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford in physics and philosophy. I am happy that I went to the United States to do my PhD in pure physics.

That is also one of the reasons why I write books. I am returning the favour to those scientists who got me turned on to science and I am always happy when I see young kids (and not-so-young kids) who tell me that my books inspired them to do science.

How did you get the gist of writing for the wider public rather than just for fellow professionals?

I also worked at a science museum when I was a kid. I did demonstrations at the Ontario Science Center, ten shows a day, and I think that was profoundly influential both in developing my ability to talk to the public about science and in figuring out what people were interested in. It also taught me how to improvise and it was useful for my lecturing in my later career.

Did you have a life goal in mind from early on, then?

No, I never had a plan that I was single-mindedly committed to. I know people like that, but I prefer to plant seeds and see which ones grow. Doing history was also influential in teaching me how to write. I have always been fairly political as well. I get angry at things and write about them. And I used to write op-eds when I was in graduate school, but they never got published. I think I sometimes write when I get angry or I need to get something off my chest.

But no, I never planned my career. Maybe because neither of my parents were academics, academia alone never seemed satisfying enough for me. I always wanted to reach out to the wider world in one way or another.

What was your first big break in writing?

At Harvard, I spoke at a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science about dark matter, and then I wrote an article for Scientific American about it. That was my first bit of public writing.

How did you end up becoming a public figure rather than just an academic?

When I was at Harvard, a role model and former professor of mine, the Nobel Laureate Steve Weinberg (whose 1977 book The First Three Minutes had, incidentally been a big influence on me and shown me that a first-rate scientist could write for a wider audience) put me in touch with his publisher. I signed on to write a book. And that led to me writing for newspapers and speaking in public.

I later got involved in the fight against creationists trying to push their ideas in public schools, and I think that is where I got a national reputation for speaking out in defence of science. As an aside, that also revived my interest in biology, which I have always somewhat regretted not knowing more about. It is a fascinating area, in some ways probably more fascinating than physics now.

What are you most proud of contributing to science?

I always think that that is for others to judge. But I am proud of many of my contributions, maybe more proud than other people are. Looking back at my work, I am surprised at the breadth of topics I have worked on and the energy that I seem to have expended. It tires me out to look at it now!

But in terms of impact, I think I was one of the earliest people to appreciate the importance of astronomy, astrophysics, and cosmology for understanding fundamental physics. An emerging area called particle astrophysics did not really exist when I was a graduate student and I got involved in that as one of the very earliest people working on that area and promoting the intersection of these two areas. By the way, it is always dangerous to work at the intersection of two fields, because people in each field might feel that you are part of neither, and it is hard sometimes. I remember when I worked at Yale the department never fully appreciated what was happening because they were not aware of particle astrophysics when I was doing it.

I think I made a bunch of significant contributions relating to the nature of dark matter and ways to detect dark matter. I think if one thing stands out, though, it is the paper I wrote with Michael S. Turner in 1995 that first argued that there was dark energy in the universe, making up about 70 per cent of the universe, the discovery of which won a Nobel Prize for Saul Perlmutter, Brian Schmidt, and Adam Riess in 2011. That was one of the times that I realised something about the universe before anybody else did, and that was very satisfying. It was hard to convince myself that I was right at the time because I was unsure if the data were correct. I remember getting a lot of resistance until dark energy was discovered, and then everyone jumped on it immediately.

In your book ‘A Universe from Nothing’, you provide a model of how the universe came about without any divine input. What do you make of that book, which caused quite a stir, when you look back now? And how do you respond to criticisms from people who say that what you meant by ‘nothing’ was not truly ‘nothing’?

Obviously, I stand by what I wrote. In retrospect, there are some things I might try to explain more clearly. But I am pretty clear that the people who say I did not show how a universe can come from nothing have not really read the book. They might say I was just talking about empty space, which is not nothing, but I talk about far more than that. What one means by ‘nothing’ is a very subtle concept and we have changed our opinion of what nothing is, as I point out in the book.

And so what I am describing is ‘no universe’. The space and time in which we now exist did not exist. Now, was there a greater whole? Was it part of a multiverse at the time? Maybe. But that is not the important issue. The important issue is whether a universe like ours did not exist and then came into existence. And that is what I mean by ‘nothing’. It was not there, and then it was there. The space and the time that we inhabit and the particles that we are made of were not there. None of that existed. That is a pretty good definition of ‘nothing’, as far as I am concerned.

Now, there is a more subtle question. Did the laws of physics exist beforehand? Maybe, maybe not. But the point of my book was to show the amazing discoveries made by scientists demonstrating that empty space was not what we thought. And another point was to ask the question, ‘What would a universe that spontaneously emerged from nothing due to the laws of quantum gravity and survived for 13.8 billion years look like?’ It would look just like the universe in which we live! That is not a proof, but it is highly suggestive and fascinating to me.

It also, among other things, gets rid of the need for a creator, at least of our universe. That is not the reason I wrote the book, I wrote it to explain the science, but it does address that last nail in the coffin, if you like, that refuge of the scoundrels of religion. Darwin had done away with the design argument for life on Earth, and I think the arguments I gave in the book go a long way toward refuting the design argument for the universe. That is what Richard Dawkins talked about in his afterword to the book. I addressed the ‘god of the gaps’ argument, which had moved from biology to physics, and the question of why there is something rather than nothing, which seems to be a big question among religious people.

You were, of course, thought of as one of the figures of the so-called ‘New Atheism’. But you were critical of Richard Dawkins for the way he approached science and religion, and that is how you first met him. Is that correct?

I was one of the leading scientific ‘atheists’, but I never referred to myself that way, because it seems silly to describe oneself by what one does not believe. But yes, I was critical of Richard for his method. I thought that you could not convince people by telling them that they are stupid. I argued that one had to be a little more seductive and our dialogue continued. The first significant time Richard and I spent together was at a symposium called ‘Beyond Belief’ in California, and it was so productive and illuminating. We decided to write a dialogue on science communication and religion for Scientific American in 2007.

At that time I was a little more apologetic about religion. I became more combative for a while after seeing what religion was doing in the United States. I had a conversation with Sam Harris in which I argued that science cannot disprove the existence of God, but that you can show, for example, that the scriptures are inconsistent, and by not being forthright about that you are simply being fearful of offending people with the truth. It is quite simple: you can either accept science or believe that the Bible contains the truth about the natural world, but not both. Those perspectives are just fundamentally irreconcilable. Of course, plenty of religious people do not take the scriptures literally, and that is fine. Indeed, if you want to mesh your scientific and religious views, you have to take the holy texts allegorically.

For a moment there, I thought you were about to say something like Christopher Hitchens radicalised you.

Well, he did! Almost more than Richard did. His book God Is Not Great (2007) informed me of a lot of things about the sociology of religion that I was not aware of. I also learned a lot about the scriptures from Christopher. I had not realised how absolutely violent and vicious they were. They were just evil. I had read the Bible and the Quran when I was younger but I had not internalised them. I skipped over a lot of the crap. I probably learned more about the Bible from Christopher and Richard than anyone else. So, yes, Christopher radicalised me. Inspired by him, I called myself an anti-theist for a while, though now I call myself an apatheist.

So the New Atheist moment has passed?

I never liked that label. What was new about it? People have been not believing in God for thousands of years! Define ‘New Atheist’ for me.

I suppose I am referring more to the historical moment, of the mid 2000s until the early 2010s, when there was this very popular group of anti-religion people speaking up in public. That cultural moment has passed.

Yes, that cultural moment has gone, and for much the same reason as all movements disappear—though I do not like to consider myself as part of any movement—which is that they fragment, just like in Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979), where you have the Judean People’s Front and the People’s Front of Judea. Incidentally, I think Life of Brian probably represents exactly what it was like at the time of Jesus, with all these messiahs going about.

The New Atheist movement, if you like, began to eat itself from within. It is a natural tendency for humans to become religious and dogmatic about things, and secular religion has taken over.

You are referring to Critical Social Justice, the term used by Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay to refer to what is more colloquially known as ‘wokeism’. If ‘wokeism’ is a dogmatic religion, how has it become so powerful and has it corrupted science?

That is a big question. I have written about it in various places, such as my Substack, so it would be better for readers to delve into those pieces. But essentially, wokeism or wokeness has made certain ideas sacred and therefore beyond criticism. Wokeism is a secular religion that makes assumptions without evidence and when those assumptions are questioned, you are subject to expulsion and considered a heretic. It has stifled and stymied the free and open enquiry and discussion that is central to academia in general and science in particular. I gave loads of examples of how wokeness has corrupted science in a seminar for the Stanford University Classical Liberalism Initiative.

Do you think this problem is getting better or worse?

I think it is getting worse. But we are at a threshold right now. With elements of the woke left cheering on actual violence against Israel, while otherwise absurdly insisting that words are violence, perhaps a new light will be thrown on them, and things might change. But it has certainly been getting worse up until this point.

To finish off, do you have any future projects in the works?

I am very excited about my Origins Project Foundation and my Origins Podcast. We have lots of great new things going on there. And I will keep writing about the issues that concern me. I am also turning now, I think, to writing a scientific memoir, which is a whole new experience for me. I am excited about that, but I also feel some trepidation. It will describe the many amazing people I have interacted with both within and outside of science as well as my own experiences within academia and outside of it, some good, some bad, that I think will be of public interest.

On Krauss’s most recent book, see the review and interview of Krauss by assistant editor Daniel James Sharp in Merion West.

On biology, see further:

‘An animal is a description of ancient worlds’ – interview with Richard Dawkins

On ‘New Atheism’, see further:

‘How three media revolutions transformed the history of atheism’, by Nathan G. Alexander

‘Christopher Hitchens and the long afterlife of Thomas Paine’, by Daniel James Sharp

On science versus religion, see further:

‘Can science threaten religious belief?’, by Stephen Law

On satire of religion, see further:

‘On trial for blasphemy: the Freethinker’s first editor and offensive cartoons’, by Bob Forder

‘Religious Privilege 2 : 0 Pastafarians’, by Niko Alm

‘The need to rekindle irreverence for Islam in Muslim thought’, by Kunwar Khuldune Shahid

On ‘wokeism’, see further:

British Islam and the crisis of ‘wokeism’ in universities – interview with Steven Greer

‘When the chips are down, the philosophers turn out to have been bluffing’ – interview with Alex Byrne

On the left, Islamists, and Gaza, see further:

‘Bloodshed in Gaza: Islamists, leftist ideologues, and the prospects of a two-state solution’, by Kunwar Khuldune Shahid

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate