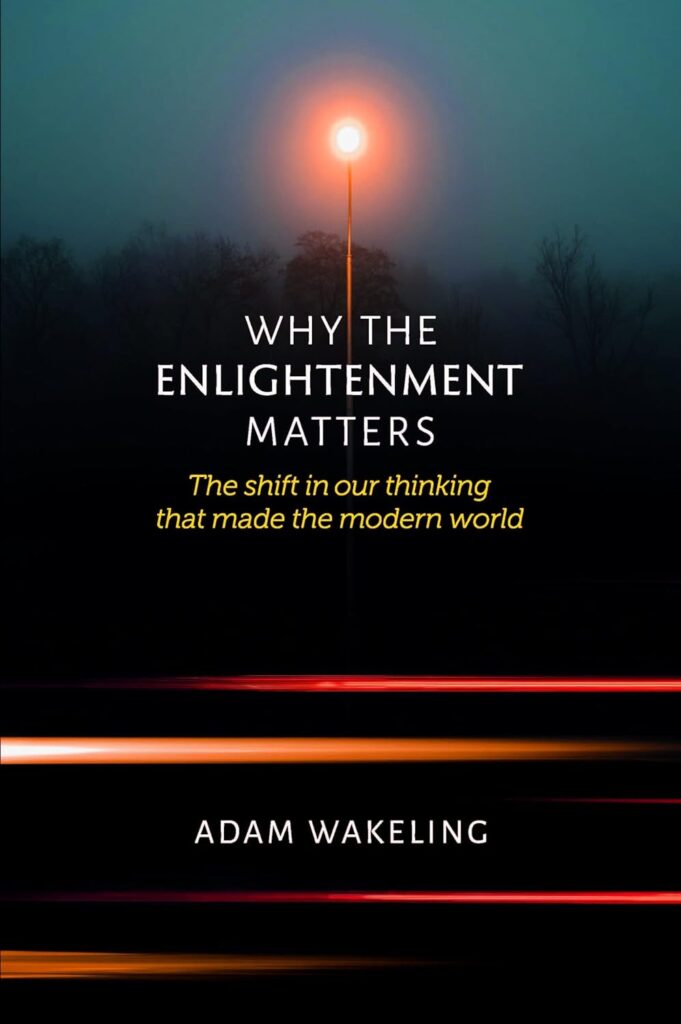

In Why the Enlightenment Matters, Adam Wakeling sets himself the ambitious task of defining the shift in thinking known as the Enlightenment that occurred in northern and western Europe between 1600 and 1800, and explaining how it made much of the modern world what it is.

Prosperous nations now enjoy benefits unimaginable throughout most of history, such as advanced health care, respect for human rights, free speech, tolerance, democracy, material comfort, scientific knowledge, education, and a reduction in wars and barbaric punishments. The author’s central thesis is that this is due to the Enlightenment. Of course, things are far from perfect – famine, disease, poverty, and dictatorship are still widespread, and the Enlightenment has an ambivalent record when it comes to racism and slavery. But today’s world would have been unrecognisable to the people of sixteenth-century Europe, when the book’s story starts.

Wakeling begins his narrative in 1553, with the burning alive of the Spanish theologian Michael Servetus in Calvinist Geneva. Servetus had denied the Trinity, proclaiming to the very end that Jesus was ‘the Son of eternal God’ and not the ‘eternal Son of God’. John Calvin, who had once been Servetus’ friend, approved of the heretic’s execution. This was the pre-Enlightenment world. In the fourteen chapters that follow, the author takes us through the unfolding story of the extraordinary changes that took place in northern and western Europe between 1600 and 1800, and gives us his explanation of why and how they happened.

Today’s world would have been unrecognisable to the people of sixteenth-century Europe.

His account is admirably comprehensive in scope, rich in historical detail, and highly readable. This reviewer is not an historian, and other curious non-historians will learn much about the manifestations and effects of Enlightenment thinking. Their common themes are principally the challenges to spiritual and political authority, and the rise of science and innovation. They include the effect of the Protestant Reformation on the breakdown of centralised authority in northern and western Europe and its role in promoting literacy. From these came the growth of toleration in the Netherlands, despite the efforts of the Dutch Reformed Church. In seventeenth-century England there was the end of rule by ‘divine right’ of English monarchs after the Civil War, and the subsequent growth of alternative justifications for government found in the ideas of Thomas Hobbes and especially John Locke. Scholastic natural law theory was modified to include rights to property and political rebellion. Developments in just war theory, especially by Hugo Grotius, had already been made urgent by the excesses of religious wars. The eighteenth century saw Adam Smith’s attempt to provide a ‘science of man’ and his role in the decline of mercantilism and the burgeoning of free trade.

Also discussed in learned detail is the history of the Enlightenment in France, where it arrived later than in the Netherlands, England and Scotland. We read of the eventual success of the Encyclopédie despite attempts to suppress or censor it, and the influence of Enlightenment ideas about the ‘Rights of Man’ on the French Revolution. Of course, the Revolution’s bloodthirsty descent into Terror, largely engineered by the fanatical Maximilien Robespierre, caused many to doubt the whole Enlightenment project.

Running parallel to these rich narratives of political changes and their attendant wars is an account of how the scientific method became established. Aristotle had already made patchy attempts at empirical enquiry into nature but had been hamstrung by his teleological theory. His ideas had become embedded in the Catholic Church’s teaching as doctrines, despite their originally provisional nature, and it was only when the Church’s authority began to fracture that Aristotelian science could be questioned. Francis Bacon exposed some ‘idols of the mind’: errors or cognitive biases such as the ‘gambler’s fallacy’, excessive reliance on personal experience, the miscommunication of correct ideas and the spread of false ideas through existing systems of philosophy. Such issues still make it hard to discern truth from prejudice in science. Yet it was only after the patient observations and hypotheses of Galileo, Kepler and Newton, in part while trying to explain the anomalous behaviour of planets, that the geocentric view of the universe was dislodged, and otherwise inexplicable celestial movements could eventually be explained in terms of a universal theory of gravitation.

The Revolution’s bloodthirsty descent into Terror, largely engineered by the fanatical Maximilien Robespierre, caused many to doubt the whole Enlightenment project.

Wakeling shows how religious authorities tried to obstruct scientific thinking, not only in Europe but further afield. In fifteenth century Samarkand, for instance, the Islamic authorities destroyed an observatory, and in sixteenth century Constantinople, a similarly impressive observatory was closed by the Sultan amid concerns that its founder, Taqi ad-Din, would be prosecuted for heresy. But for some reason, the Enlightenment prevailed in northern and western Europe, whereas the pockets of Enlightenment thinking that had sprung up in other places, such as the Ottoman Empire and India, never took off. Moreover, in the eighteenth century, the nations where the Enlightenment occurred began to overtake the rest of the world in technological knowledge and economic power, and in the nineteenth century brought massive improvements to the living standards of ordinary people.

The final chapter of the book is especially interesting and potentially controversial, as it explores why the Enlightenment was successful in Europe and north America but not elsewhere. It brings us back to the author’s account, given near the start of the book, of what the shift in thinking that defined the Enlightenment really amounted to. In his view, it consisted of five simple elements: recognition of the limits of reason, empirical thinking, toleration of dissent, universality, and progress. Of course, in a broad sense the Enlightenment was a rational project, in that its thinkers used reason to question authority and dogma. But they rejected the notion that pure reason could reach truths that, as it happened, only empirical methods could reveal. Once dogmas were questioned, dissent was inevitable, and the issue of toleration became unavoidable. Wakeling argues that it was precisely this shift in thinking that explains the success of the countries where the Enlightenment took root.

This is controversial, not only because fashionable post-colonial theory is suspicious of the Enlightenment, but also because some writers think the flourishing of Western civilisation is traceable to Greco-Roman times and Christianity.

Wakeling’s rebuttal of the latter notion is, in essence, that the Enlightenment’s empirical style of thinking and its toleration of dissent amounted to a radical break with the past. There was much that was bad about the Greco-Roman world, and much of the history of Christianity is one of intolerance.

[The Enlightenment] consisted of five simple elements: recognition of the limits of reason, empirical thinking, toleration of dissent, universality, and progress.

In reply, one might say that it was the best features of the classical world, such as Greek democracy and philosophy that inspired Western civilisation, and that it was not so much Christianity as its connection to state power from the fourth century onward that explains why the Enlightenment took so long to occur. As Wakeling concedes, Jesus reportedly said that his Kingdom was not of this world, and Christians were persecuted in the Roman Empire until 313 AD. These questions are of course complex, but whether or not Christianity ultimately contributed to the Enlightenment, Wakeling is persuasive in arguing that the latter was almost certainly a major factor in Western success, due to its distinctive style of thought.

I highly recommend this book both for scholars and the general reader. It is a rare combination of erudition and lucidity; it makes its thesis plain from the outset and it sets out its evidence clearly and thoroughly. Since it is primarily an historical analysis, it does not respond to contemporary philosophical critiques of the Enlightenment, such as that of Alasdair MacIntyre. Some thinkers might regard the Enlightenment view of human nature as naïve and lacking in spiritual insights into our darkest flaws: a world of rights and prosperity may be lacking in love and humility. But for all that, the Enlightenment provided fertile soil for the better as well as the worse aspects of humanity, and readers will find this stimulating book an invaluable resource.

Adam Wakeling, Why the Enlightenment Matters: The shift in our thinking that made the modern world, is published by Australian Scholarly Publishing, May 2023.

See also Wakeling’s article for the Freethinker, Do we need God to defend civilisation?

1 comment

Hi – I wish our schools taught Enlightenment / Age of Reason philosophy – that is where my efforts lie.

I love what you have said and I will read Adam Wakeling’s book BUT you and he are preaching to the converted.

Wonderful words and “the bleeding obvious” but they will not be heard by our kids, politicians, white van man, the monarchy and Anglicanism.

I have written two books, on Amazon, which use lighter language and have been read by 10s of people 😉 Sad eh?

Anyhow please review my book “The Faith Virus” self published last year and my other one, just published on British broken politics,

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate