Although elaborate hate speech laws can make it extremely difficult, we have the right to freedom of expression in Britain. Generally speaking, musicians are free to express their opinions. Morrissey can voice his opposition to mass immigration and concerns about the erosion of English identity while Stormzy can take the stage at Glastonbury and get his audience of over 200,000 people to yell ‘fuck the government’, both with impunity. The ability of artists to hold those in positions of power accountable is a fundamental civil liberty that ensures the maintenance of political equilibrium in a liberal democracy.

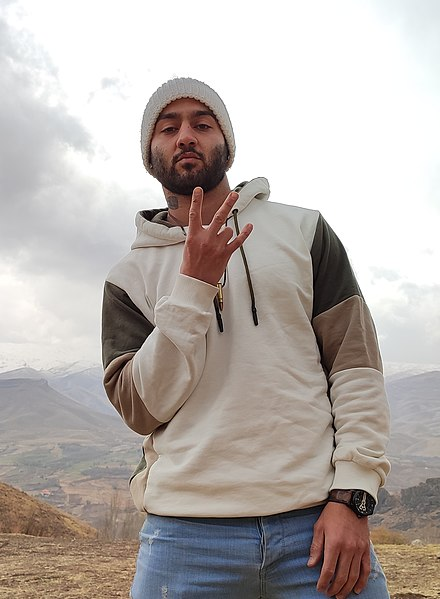

While our system has many flaws—cough, Scotland—we have never executed a musician for speaking their mind, as far as I can recall. And yet the Iranian rapper Toomaj Salehi must face the horrifying reality of that exact situation. Salehi was given a death sentence in April this year after the Islamic Revolutionary Court of Isfahan accused him of ‘waging war against god’.

Salehi is a vocal opponent of the Islamic Republic. The right to free speech is guaranteed to well-known socially conscious rappers in the West, such as Talib Kweli and Immortal Technique, but Salehi was not accorded the same protection to express himself. In Iran, hip-hop is strictly forbidden. Artists typically use pseudonyms to get around the regime; Salehi, on the other hand, has always gone by his real name.

The 33-year-old is at the forefront of socially conscious hip-hop in Iran and was a pioneer of the Rap-e Farsi (Persian-language rap) movement. His lyrics advocate for greater rights for women and workers while addressing injustice and inequality. In tracks like ‘Pomegranate’, he sings ‘Human (life) is cheap, the labourer is a pomegranate, Iran is a wealthy, fertile land,’ alluding to workers as nothing more than fruit to be squeezed. However, the majority of his vitriol is aimed at the Islamic Republic itself. In his most well-known song, ‘Soorakh Moosh’ (‘Rat Hole’), he condemns all those who support the corrupt regime and turn a blind eye to oppression and injustice.

It was songs like this that initially drew the state’s attention to him. Iran’s security forces detained Salehi on September 13 2021 and accused him of ‘insulting the Supreme Leader’ and ‘propaganda against the regime’. He was granted a six-month suspended sentence and released from prison after serving more than a week.

Salehi’s case serves as a microcosm of the fractures that exist in Iranian society more than 40 years after the revolution of 1979. Since the overthrow of the Shah, the country has been ruled as an Islamic republic, with women required to cover their hair in strict compliance with Islamic modesty laws. The ageing clerical elite—Ayatollah Khamenei is 85— is at variance with the majority of its citizens, who were born after the revolution. Many of them are concerned with personal freedoms and financial security—50% of Iranians are living in absolute poverty—rather than religious purity. Salehi speaks for a generation of disillusioned youth.

His activism extends beyond words: he has supported a number of social causes, most notably the Woman, Life, Freedom movement and the September 2022 protests, which were sparked by the death in custody of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian woman who was detained by the police after she was accused of wearing an ‘improper’ hijab. Subsequent anti-hijab demonstrations, which saw thousands of people take to the streets calling for women’s rights and the dissolution of the Islamic Republic, with many of them burning hijabs, spread across the country and resulted in over 22,000 arrests and over 530 deaths.

To support the women-led uprising, Salehi released two songs. ‘Battlefield’, which was released in early October 2022, contains the lyrics, ‘Woman, life, freedom, we will fight to the death/ Shoulder to shoulder like a defensive wall/ I believe in solidarity like divine faith/…We are thirsty for freedom’. A few weeks later, he released a song containing the lines, ‘44 years of your government, it is the year of failure/… Someone’s crime was dancing with her hair in the wind / Someone’s crime was that he or she was brave and criticised [the government]’.

On October 30, 2022, Salehi was detained once more and charged with spreading ‘propagandistic activity against the government’. He received a prison sentence of six years and three months in July 2023. The Supreme Court granted him bail in November after he had been imprisoned for more than a year, including 252 days in solitary confinement. When he was free, he posted a video to his official YouTube account from outside the jail where he had been held, claiming he had been tortured—having his arms and legs broken and given shots of adrenaline to keep him awake. He was swiftly reimprisoned.

For the crime of talking, or, in the words of the Isfahan court, ‘spreading corruption on earth’, Salehi was sentenced to death on 24 April 2024. As of writing, the case is awaiting appeal.

This is not an isolated case. Saman Yasin is another musician who suffered a similar fate. The Supreme Court commuted the Kurdish rapper’s death sentence, which had been imposed after his arrest during the 2022 protests, to five years in prison. Yasin has allegedly been tortured and prohibited from interacting with others.

Under the iron fist of Khamenei, Iran crushes dissent. Amnesty International reports that 853 people were executed in Iran in 2023—the highest number since 2015 and a 48% increase from the year before. 74% of executions reported globally in 2023 occurred in the Islamic Republic.

Women who violate the dress code have also been severely punished. Ironically, a few weeks prior to World Hijab Day this year, an Iranian woman and activist by the name of Roya Heshmati was detained for 11 days, fined $300, and whipped 74 times after she was caught on social media without a headscarf. Salehi is right to use his platform to expose the violent misogyny that permeates totalitarian Islamic societies like Iran. The hijab is, quite simply, a symbol of oppression, not liberation, whatever some in the West might think.

Freedom of expression is essential for musicians. All artists must be free to question, challenge, and criticise authority. The tyrant’s empire is built on a foundation of censorship. Words mean little when no one can hear them. Salehi’s three million Instagram followers have contributed to the attention his case has received in the West. While we can all lament the loss of meaningful conversation on social media, we cannot deny its power to instantly connect millions of people.

Music is a powerful medium for telling stories. And we can spread that message by using the internet. A new wave of youthful, politically engaged musicians is emerging thanks to social media, as shown by Salehi and many others. See also the rise of dissident rappers in Russia such as Oxxxymiron and FACE—the latter of whom Putin has designated as a foreign agent.

Nobody should ever be sentenced to death or even arrested for speaking their mind. Those who foolishly believe they can use violence to counter the pen do so because they understand that most people will be intimidated into silence. His extraordinary bravery and conviction bear witness to the principles that Salehi has upheld throughout his life. As Nassim Nicholas Taleb writes, ‘Courage is the only virtue you cannot fake.’

While we in the West take the right to free speech for granted, we should praise courageous people like Saman Yasin and Toomaj Salehi—people who are prepared to risk their lives in order to challenge the hegemony of the Ayatollah and his despotic, theocratic regime.

Related reading

The ‘Women’s Revolution’: from two activists in Iran, by Rastine Mortad and Sadaf Sepiddasht

The need for a new Enlightenment, by Christopher Hitchens

The hijab is the wrong symbol to represent women, by Khadija Khan

Image of the week: celebrating the death of Ebrahim Raisi, the Butcher of Tehran, by Daniel James Sharp

Secularism is a feminist issue, by Megan Manson

Faith Watch, November 2023, by Daniel James Sharp

When does a religious ideology become a political one? The case of Islam, by Niko Alm

‘The best way to combat bad speech is with good speech’ – interview with Maryam Namazie, by Emma Park

Religion and the Arab-Israeli conflict, by Kunwar Khuldune Shahid

‘Nature is super enough, thank you very much!’: interview with Frank Turner, by Daniel James Sharp

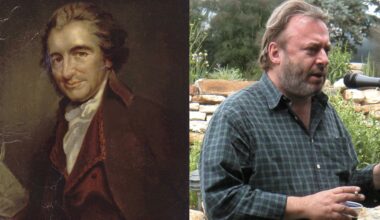

The rhythm of Tom Paine’s bones, by Eoin Carter

Consciousness, free will and meaning in a Darwinian universe: interview with Daniel C. Dennett, by Daniel James Sharp

Celebrating Eliza Flower: an unconventional woman, by Frances Lynch

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate