Read Part One here.

Readers may recall that during the Vietnam War, US soldiers were wont to justify their presence in that country by claiming they were there to ‘kill a Commie for Christ’.

Before attempting to unpack this phrase, let me suggest that it encapsulates the very essence of the relationship between religion and war. I also suggest that it offers at least a sliver of hope that the historically deeply intertwined relationship between the two might one day be severed.

In October 2011, Dylan Ratigan wrote an article for the HuffPost entitled ‘How Did Our Oil Get Under Their Sand?’ Written some eight years after the US invasion of Iraq in March 2003, Ratigan argued that ‘the only real consistency in policy-making is Washington’s commitment to war and oil, and increasingly often, war for oil.’ Suppose this is an accurate description of at least one of the US government’s major motivations for the Iraq War. In that case, it’s a far cry from the initial rationale for that war presented to the American people.

During an interview on CNN on September 8, 2002, then-National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice infamously warned that Saddam Hussein could be close to producing a nuclear weapon. When asked just how close Saddam was to ‘developing a nuclear capacity’, Rice replied: ‘The problem here is that there will always be some uncertainty about how quickly he can acquire nuclear weapons. But we don’t want the smoking gun to be a mushroom cloud.’

In contrast to Rice’s assertion, Scott Ritter, a former UN weapons inspector in Iraq, reported the same day that there was no ‘smoking gun’ inasmuch as the Bush administration had failed to substantiate its case that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction. Ritter’s conclusion was later substantiated prior to the war by onsite inspections conducted by both the United Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission and the International Atomic Energy Agency.

Needless to say, the testimony of Scott Ritter and other reputable organisations did nothing to dissuade the Bush administration from invading Iraq on March 19, 2003. The result would be the violent deaths of between 268,000 and 295,000 people between March 2003 and October 2018. It also did nothing to dissuade many Christian clergy in the US from voicing their full support for the invasion. For example, Charles Stanley, pastor of the First Baptist Church of Atlanta and a former Southern Baptist Convention president, stated in a sermon broadcast internationally on TV: ‘Throughout Scripture, there is evidence that God favors war for divine reasons and sometimes uses it to accomplish His will. He has also given governments and their citizens very specific responsibilities in regards to this matter.’

Further, Leith Anderson, president of the National Association of Evangelicals, noted that ‘Most evangelicals in America subscribe to the theological position called ‘Just War Theory,’ that it is morally justified to go to war under certain conditions.’ Similarly, Prison Fellowship founder Charles Colson, a Baptist, argued in 2002 that the classical definition of Christian just war theory should be ‘stretched’ to accommodate a new age in which terrorism and warfare are intertwined. Colson alleged that ‘out of love of neighbor, then, Christians can and should support a preemptive strike’ on Iraq to prevent Iraqi-based or -funded attacks on the United States or its allies. Colson was one of the signatories to the Land letter, a letter sent by several evangelical Christian leaders to Bush giving their ‘just war’-based support to the invasion of Iraq.

As the above quotations indicate, one of the most frequent justifications for Christian support of war, shared by Catholics and Protestants alike, is the belief in ‘just wars’. Christian just war theory, first developed by Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430) and later by Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), was designed to provide a reliable guide for determining if a specific war was in accord with the teachings of Jesus Christ. Laying aside what Jesus actually said about the use of violence for the moment, just war doctrine clearly empowered the Pope, as Vicar of Christ on earth, to determine which war, if any, the faithful should fight (and die) in.

Just war theory, at its most basic, declares that a war must be fought for a just cause, i.e., it must correct a grave, public evil. Further, only duly constituted public authorities may wage war exclusively for the reasons set forth as a just cause. Arms may not be used in a futile cause or in cases where disproportionate measures are required to achieve success. Finally, force may be used only after all peaceful alternatives have been seriously tried and exhausted and the force used must be proportional to the injury suffered. That is to say, the harm caused by the war must not be greater than the harm to be eradicated.

If one believes that the use of force is sometimes unavoidable, it is difficult to fault just war theory, at least at the theoretical level. But what of historical practice? In the long history of the Roman Catholic Church, has the Church, i.e., the Pope, ever formally declared that even one of the numerous wars occurring since the adoption of just war doctrine is ‘unjust’? The surprising answer is ‘no’. No Pope has ever issued a formal declaration using their full papal authority to categorically label a specific war as unjust. Not even in the Second World War did Pope Pius XII see fit to formally declare that Nazi Germany, with its sizable Catholic population, was fighting an unjust war. That said, it is true that numerous Popes have used their moral and spiritual authority to speak out strongly against certain wars. For example, Pope John Paul II was strongly opposed to the Iraq War. Nevertheless, he, too, failed to issue a formal declaration explicitly stating that that war was unjust.

What of the opposite case, i.e., have any Popes declared that certain wars have been ‘just’? Here the answer is an unambiguous ‘yes’. Successive Popes declared the multiple Crusades of the late 11th to 13th centuries to be just wars. At the Council of Clermont in 1095, Pope Urban II framed the very First Crusade as a penitential act, a holy pilgrimage, and a just war to reclaim the Holy Land and protect Eastern Christians from Muslim rule. Urban further promised spiritual rewards, including indulgences (remissions of sins), to those who took up the sword and the cross.

Following in Urban’s footsteps, various Popes issued bulls (formal papal decrees) supporting and legitimising the Crusades. For example, Pope Eugenius III issued the bull Quantum praedecessores in 1145, calling for the Second Crusade, and Pope Innocent III issued Post miserabile in 1198, urging the launch of the Fourth Crusade. These papal bulls not only called for the Crusades but also outlined the spiritual benefits, protections, and financial support to be had by those who participated in them. They promoted the Crusades by emphasising themes of Christian duty, divine favour, and spiritual rewards, further reinforcing the just war narrative.

Today, thanks to a reconsideration of the historical relationship between Christians and Muslims set in motion by the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), the Church has undergone a major change in its outlook. In 1976, Paul Johnson, an English Catholic historian, described the Crusades as follows:

The Crusades were not missionary ventures but wars of conquest and primitive experiments in colonization; and the only specific Christian institutions they produced, the three knightly orders, were military… A Crusade was in essence nothing more than a mob of armed and fanatical Christians. Once its numbers rose to over 10,000 it could no longer be controlled, only guided. It might be used to attack Moslems, or unleashed against Jews, or heretics… The fall of Jerusalem [in 1099] was followed by a prolonged and hideous massacre of Moslems and Jews, men, women and children… In general, the effect of the Crusades was to undermine the intellectual content of Islam, to destroy the chances of peaceful adjustment to Christianity, and to make the Moslems far less tolerant: crusading fossilized Islam into a fanatic posture.

In short, over the centuries just war doctrine has been, at least in practice, little more than a moral fig leaf to disguise an age-old pattern, i.e., what we (the Church and its adherents) do is by definition ‘just’ (no matter how horrendous) and what others do is not. Just how far just war doctrine varies from, if not violates, Jesus’ teachings is clear when we turn to the New Testament. Jesus not only advocated non-violence but directed his followers to love one’s enemies. Key passages include the Sermon on the Mount where Jesus says ‘Blessed are the peacemakers’ and urges his followers to turn the other cheek if they are attacked. These teachings were foundational for early Christians, with substantial evidence suggesting that early Christian communities leaned heavily towards pacifism. Early Church fathers like Tertullian (c. 155 – c. 220), for example, argued that Christians should not participate in military service, stating that ‘Christ, in disarming Peter, disarmed every soldier.’

Nevertheless, by the time of Constantine I in the 4th century, Christianity was becoming enmeshed with the militaristic Roman state. As a result, the Church’s stance on violence and military service began to change. It was this change that prompted figures like Augustine to a shift in thinking, accommodating the realities of Christians to the political power of the state. Note, too, that this shift not only led to Christianity’s acceptance by the Roman state, but it greatly enhanced the influence, prestige, and wealth of the prelates themselves.

As for Christianity and war specifically, one of the most momentous changes occurred when, in the aftermath of Constantine’s victory at the Battle of Milvian Bridge in October 312 (which he came to attribute to the support of the Christian God), he agreed to exempt Christian clergy (but not laity) from service in the Roman army, among other benefits. Constantine did this in exchange for the clergy’s commitment to pray for the victory of his soldiers. This marked the beginning of the military chaplaincy we have today and explains the origins of why in the UK and US, for example, chaplains remain unarmed even as they meet the ‘spiritual needs’ of soldiers on the battlefield.

The importance of the role of military chaplains is explained in the following article that appeared in the Associated Press in 2004 during the Iraq War:

As American troops cope with life—and death—on a faraway battlefield, military chaplains cope with them, offering prayers, comfort and spiritual advice to keep the American military machine running… Chaplains help grease the wheels of any soldier’s troubled conscience by arguing that killing combatants is justified.

Capt. Warren Haggray, a 48-year-old Baptist Army chaplain said: “I teach them from the scripture, and in the scripture I can see many times where men were told…to go out and defeat the enemy. This is real stuff. You’re out there and you gotta eliminate that guy, because if you don’t, he’s gonna eliminate you.” [Emphasis mine]

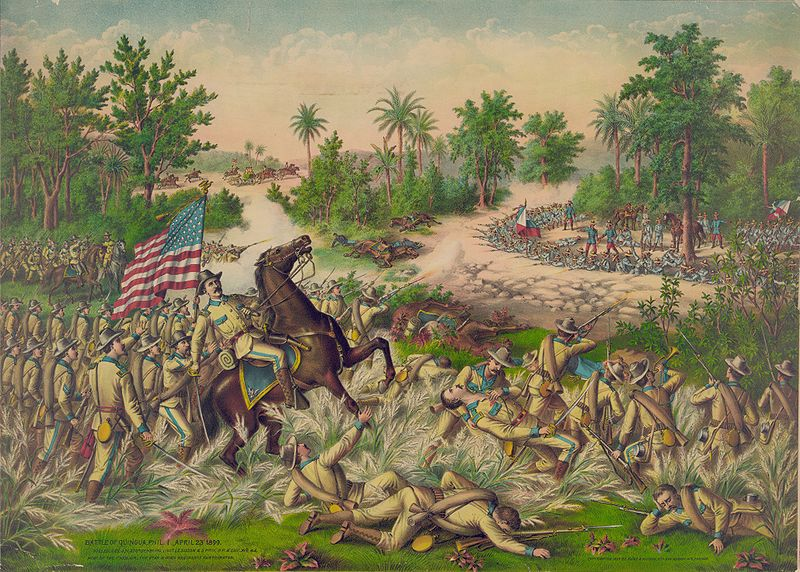

Note, too, that it is not just military chaplains who ‘grease the wheels’ of those who are engaged, directly or indirectly, in the killing business. That is to say, those who order soldiers into battle also benefit from Christianity’s alliance with the state. For example, at the time of the Spanish-American War in 1898, following Spain’s defeat and America’s takeover of the former Spanish colony of the Philippines, President McKinley invited a group of Methodist church leaders to the White House in 1899. He told them:

I walked the floor of the White House night after night until midnight; and I am not ashamed to tell you, gentlemen, that I went down on my knees and prayed to Almighty God for light and guidance more than one night. And one night late it came to me this way—I don’t know how it was, but it came … that there was nothing left for the US to do but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos, and uplift them and civilize and Christianize them, and by God’s grace do the very best we could by them, as our fellow men for whom Christ also died. And then I went to bed, and went to sleep, and slept soundly, and the next morning I sent for the chief engineer of the War Department (our map-maker), and I told him to put the Philippines on the map of the United States.

The Spanish, albeit Roman Catholics, had used the same ‘Christianizing’ mission to justify their own colonisation of that country from 1565. Nevertheless, none of the US Protestant clergy present opposed the colonialist decision of a president who had ‘went down on [his] knees’ to ask for divine guidance. In the Philippine-American War that followed between 1899 and 1902, the total number of Filipino casualties is estimated to have been between 220,000 and 250,000—all in the name of being uplifted, civilized, and ‘Christianized’ (i.e., ‘Protestantized’) by the US. The unity of Christianity and the state that began under Constantine has for many centuries provided both spiritual and material blessings for Christian soldiers, their political rulers, and their clergy throughout the world, and not only in the US.

At this point, I would not be surprised if some readers may be thinking, ‘Why is the author of this article so relentless in his criticism of Christianity? Wasn’t he once a Christian missionary in Japan? Is it perhaps because, now that he’s a Buddhist priest, he thinks Buddhism is so different from Christianity, i.e., a true religion of peace?’

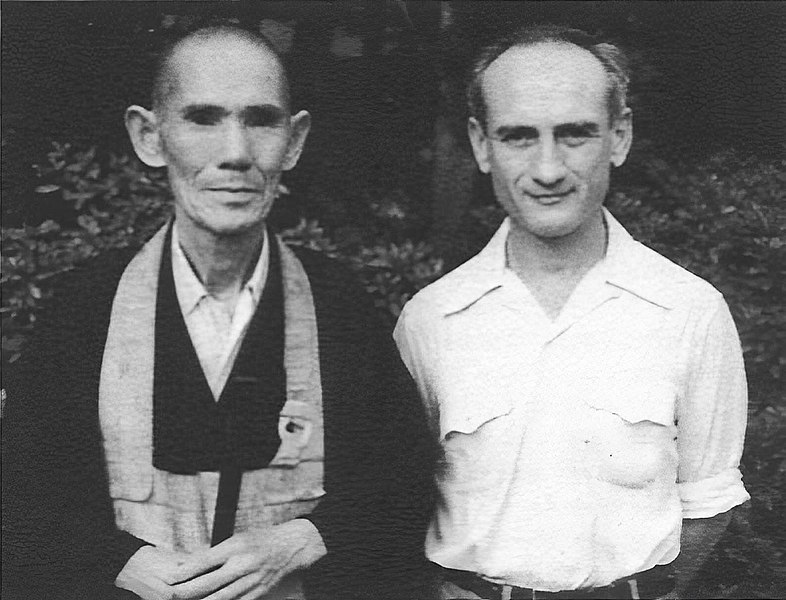

While the author did once labour under that misapprehension, it is no longer the case, for like all world religions, Buddhism, despite its undeserved reputation as a religion of peace, is not substantially different when viewed in its actual historical practice. One of the first times I realised this was when I read a quotation from D.T. Suzuki, famous for his introduction of the (Rinzai) Zen sect of Buddhism to the West.

At the time of Imperial Japan’s attempt to colonise Korea, leading to the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, Suzuki wrote an English-language article entitled ‘A Buddhist View of War’. He concluded the article with the following appeal to Japan’s soldiers:

When our ideals clash, let there be no flinching, no backsliding, no undecidedness, but for ever and ever pressing onwards. In this kind of war there is nothing personal, egotistic, or individual. It is the holiest spiritual war… Let us then shuffle off this mortal coil whenever it becomes necessary, and not raise a grunting voice against the fates… Resting in this conviction, Buddhists carry the banner of Dharma over the dead and dying until they gain final victory.

Simply stated, Suzuki was exhorting Japanese soldiers to simply die without complaint in ‘the holiest spiritual war’ since their deaths would ensure that the Dharma (i.e., Buddhism) reigned supreme. Placed within historical context, Suzuki’s admonition is unsurprising inasmuch as Suzuki’s own Zen master, Shaku Sōen, a Buddhist military chaplain in the same conflict, said essentially the same thing. In explaining the motivation for his service, Sōen wrote:

I wished to have my faith tested by going through the greatest horrors of life, but I also wished to inspire, if I could, our valiant soldiers with the ennobling thoughts of the Buddha, so as to enable them to die on the battlefield with the confidence that the task in which they are engaged is great and noble.

In the preceding quotation, if one were to replace ‘the ennobling thoughts of Buddha’ with ‘the ennobling thoughts of Christ’, I suggest you would have, at least doctrinally speaking, a nearly identical stance.

Further, when Leo Tolstoi, the famous Russian author and pacifist, sent a letter to Sōen asking him to sign a joint statement denouncing the war between their two peoples, Sōen responded:

Even though the Buddha forbade the taking of life, he also taught that until all sentient beings are united together through the exercise of infinite compassion, there will never be peace. Therefore, as a means of bringing into harmony those things that are incompatible, killing and war are necessary.

In the following years, as Imperial Japan continued its colonisation of additional Asian countries, Buddhist support for this effort, on the part of all of Japan’s many Buddhist sects, became ever more strident. It reached the point that even the fundamental Buddhist precept proscribing the taking of life proved no impediment to those espousing support for Japan’s war effort. For example, in 1943, at the height of the Second World War, Sōtō Zen master Yasutani Haku’un wrote:

One should, fighting hard, kill everyone in the enemy army. The reason for this is that in order to carry [Buddhist] compassion and filial obedience through to perfection it is necessary to assist good and punish evil… Failing to kill an evil man who ought to be killed, or destroying an enemy army that ought to be destroyed, would be to betray compassion and filial obedience, to break the precept forbidding the taking of life.

Not content with advocating the killing of the enemy army, Yasutani, like the Nazis, found yet another group to demonise—the Jews. Yasutani wrote:

We must be aware of the existence of the demonic teachings of the Jews… They are caught up in the delusion that they alone have been chosen by God and are [therefore] an exceptionally superior people… The result of all this is a treacherous design to usurp [control of] and dominate the entire world, thus provoking the great upheavals of today. It must be said that this is an extreme example of the evil resulting from superstitious belief and deep-rooted delusion.

Perhaps the most amazing thing about D.T. Suzuki, Yasutani Haku’un, and the many other wartime Japanese Zen Buddhist leaders is that even today large numbers of Western Zen Buddhists continue to revere them as the very embodiment of ‘enlightenment’. And lest there are readers who think that statements like the above are limited to either wartime Japanese Zen masters or Japanese Buddhist leaders in general, we need only look at the more recent statement of Thai monk Kitti Wuttho who, in 1976 in the aftermath of a massacre of leftist protesters, claimed: ‘Killing communists is not killing persons because whoever destroys the nation, the religion, or the monarchy, such bestial types are not complete persons. Thus we must intend not to kill people but to kill the Devil (Mara); this is the duty of all Thai.’ Based on this statement, one can assume Venerable Wuttho would have had no objection to the statement ‘Kill a Commie for Buddha’.

Were space available, I could give examples of similar statements made by the leaders of all the world’s major faiths. With regard to Islam, for example, on 23 April 2004, the well-known Iraqi Shiite Muslim cleric Muqtada al-Sadr encouraged his followers to rise up against the US occupation of Iraq. He said:

Tell America, tell all the world, tell the Governing Council, that I have God by my side and they have the devil by theirs, and to my followers, I say, do not think we are not powerful. We can fight and defeat anyone!

A few months later, he crowed:

The only reward for those who make war on Allah and on Muhammad, his messenger, and plunge into corruption, will be to be killed or crucified or have their hands and feet severed on alternate sides, or be expelled from the land.

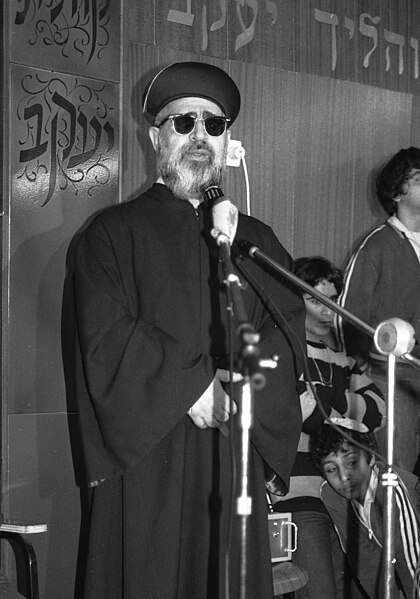

Judaism, too, is no exception to religion-endorsed warfare, as revealed in the current mass murder of Palestinians being carried out by the Jewish state of Israel. While contemporary statements by Israeli leaders calling the Palestinians ‘human animals’ and the like are well known, it is important to recall that a denial of the shared humanity of Palestinian Arabs and Israeli Jews has long been the staple of some Israeli Jewish rabbis.

In a 2001 sermon, the now deceased Ovadia Yosef, then the Sephardi Chief Rabbi of Israel and a founder of the ultra-orthodox Shas religious political party, exclaimed: ‘May the Holy Name visit retribution on the Arab heads, and cause their seed to be lost, and annihilate them… It is forbidden to have pity on them. We must give them missiles with relish, annihilate them. Evil ones, damnable ones.’ Twenty-three years later, Rabbi Yosef’s words are being enacted by the Israeli military in Gaza.

Finally, readers will recall that I found a sliver of hope in the phrase ‘Kill a Commie for Christ’. By this, I meant that history suggests that when we see the ‘other’ as an extension of, or a reflection of, our self, we cannot easily kill them. Instead, we must first believe (or be led to believe) that the ‘other’, in this case, the ‘Commie’, is the very incarnation of evil while at the same time believing (or being led to believe) that we are the ‘good guys’ (and increasingly ‘good gals’) killing for a ‘righteous cause’, e.g., on behalf of Jesus, the ‘Prince of Peace’.

But what happens when soldiers discover that the enemy is actually an extension of themselves? That they are fellow human beings with the same wants, desires, fears, and, indeed, weaknesses? In this connection, I recall my own personal experience as a civilian college instructor in the US Navy’s Program for Afloat College Education. In 1980 I was assigned to teach on board the USS Kirk, a destroyer escort homeported in Yokosuka, Japan. In addition to the Japanese language, I taught a course on modern Chinese history as the ship patrolled the Taiwan Strait on a ‘peace-keeping mission’.

At the beginning of the course, my sailor-students expressed interest in learning more about their putative enemy, the ‘ChiComs’ (derogatory GI slang for Chinese Communists). Knowing of their prejudice, I chose Edgar Snow’s famous work Red Star Over China as the course text due to its sympathetic portrayal of the Communist guerrilla movement led by Mao Tse-tung (aka Mao Zedong). Sailors were shocked to learn, for example, that in the late 1930s, Mao’s opponent, Chiang Kai-shek, leader of the Nationalist Chinese and a professed Christian, expressed his admiration for fascism and believed that it held potential for China’s future development. ‘So we’re here in the Taiwan Strait risking our lives to defend fascism?’ they asked incredulously.

Toward the end of the class one of the sailors, having long abandoned the term ‘ChiCom’, said:

‘You know, Professor, if I’d been in the position of impoverished, landless Chinese peasants, faced with the choice of supporting either Chiang and his landlord backers or Mao, I would have become a Communist guerrilla, too!’ Other students in the class nodded in agreement. Needless to say, the purpose of the class was not to create ‘Communist guerrillas’ but, rather, to understand what led impoverished Chinese youth to become revolutionaries.

For this reason, I was heartened to see that with the knowledge they had acquired the sailors came to recognize the humanity, and understand the motives, of those who heretofore had been presented to them as evil incarnate. However, following the voyage, I was fired from my teaching position at the direction of the headquarters of the Seventh Fleet in Japan. The headquarters wrote my employer, Chapman College, explaining that ‘Brian Victoria is considered a threat to military order and discipline and must never be allowed to teach on board a Seventh Fleet ship again.’ So it goes…

Readers of Part One will recall that I identified the ongoing ‘tribal mentality’ of Homo sapiens as the root cause of our willingness to kill the ‘other’ in ever more massive numbers and with ever more lethal means. While all of today’s major religions claim to espouse universal truth and promote peace, when push comes to shove, religious leaders, almost without exception, resort to a tribal mentality that endorses if not promotes the murderous actions of their tribe’s (aka nation’s) soldiers. In doing so, they provide both their political leaders and the soldiers under their direction with the belief that they are acting righteously, ethically, with worthy goals that justify the means, no matter how cruel and heartless they may be.

Religious leaders also typically assure soldiers’ next of kin that in the event their loved ones fall in battle, they will be rewarded with some form of an afterlife, e.g., eternal life in the heaven of Christianity or rebirth in Buddha Amitābha’s ‘Pure Land’ in the case of Buddhism. At the same time, religious leaders enjoy the respect and approbation of their tribe/nation, for even should ‘their side’ lose the war, religious leaders are there to offer moral support and comfort, eulogising the patriotic ‘selflessness’ of the fallen and assuring their loved ones that the fallen have gone to a ‘better place’ and are ‘at peace’. In short, whether the war is won or lost, religious leaders, who need not risk their own lives on the battlefield, typically end up as the ‘winners’.

Given this, is there any hope?

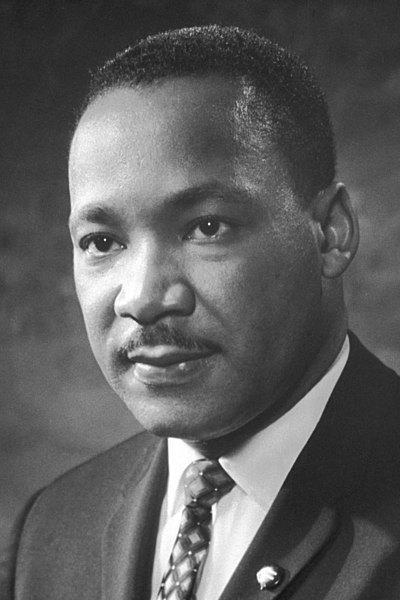

In light of the ongoing, and widespread, strength of the tribal mentality of Homo sapiens, there is only one solution. First, we need to educate both ourselves and others regarding the true nature of conflicts (almost always fought in the self-interest of the rich and powerful on both sides). Thereafter, we need to educate as many as possible to see the same humanity in others as they see in themselves, regardless of differences in skin colour, ethnic or national identity, religious affiliation (or lack thereof), gender, gender orientation, etc. Should we fail to do this, we would be well to recall the words Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke in his Christmas Sermon of Sunday, December 24, 1967:

[We] must either learn to live together as brothers [and sisters] or we are all going to perish together as fools.

Related reading

White Christian Nationalism is rising in America. Separation of church and state is the antidote. By Rachel Laser

Reproductive freedom is religious freedom, by Andrew Seidel and Rachel Laser

What has Christianity to do with Western values? by Nick Cohen

Secular conservatives? If only… by Jacques Berlinerblau

A reading list against the ‘New Theism’ (and an offer to debate), by Daniel James Sharp

Image of the week: Filippino Lippi’s ‘Triumph of St Thomas Aquinas over the Heretics’, by Daniel James Sharp

How the Roman Empire became Christian: Catherine Nixey’s ‘The Darkening Age’ and ‘Heresy’ reviewed, by Charles Freeman

The need for a new Enlightenment, by Christopher Hitchens

The roots of political Buddhism in Burma, by Hein Htet Kyaw

Britain’s liberal imam: Interview with Taj Hargey, by Emma Park

The radicalisation of young Muslims in the UK: an ongoing problem? by Khadija Khan

Bloodshed in Gaza: Islamists, leftist ideologues, and the prospects of a two-state solution, by Kunwar Khuldune Shahid

Religion and the Arab-Israeli conflict, by Kunwar Khuldune Shahid

Is the Israel-Palestine conflict fundamentally a nationalist, not a religious, war? by Ralph Leonard

Israel’s war on Gaza is a war on the Palestinian people, by Zwan Mahmod

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate