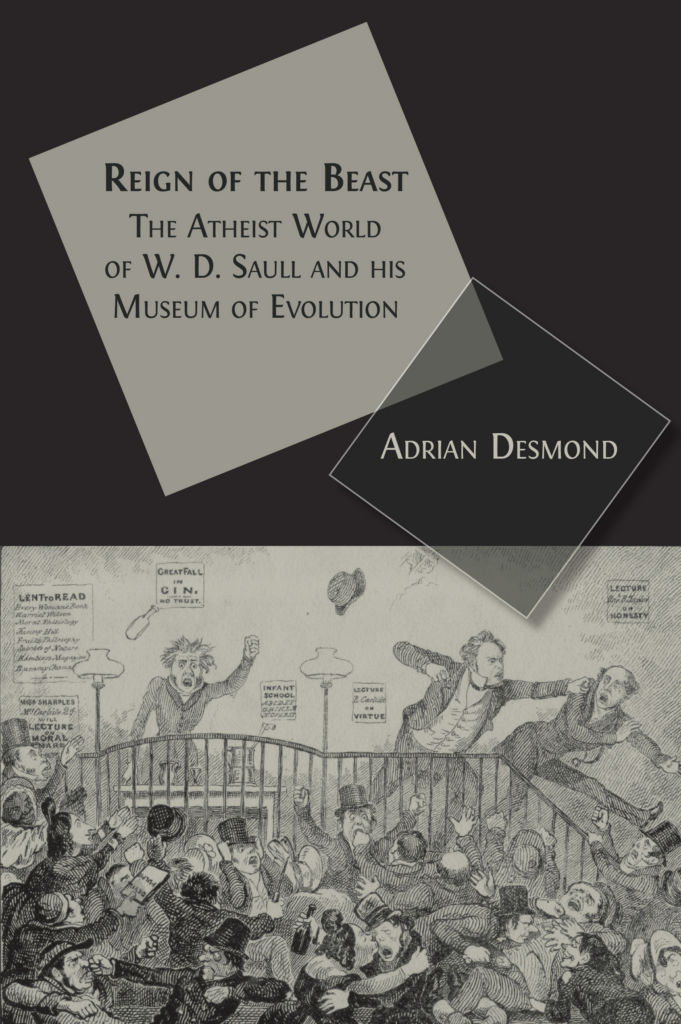

Adrian Desmond’s recent book Reign of the Beast: The Atheist World of W. D. Saull and his Museum of Evolution is surely far too long for mere mortals to digest, despite the fact that the writing flows along with the swiftness and lucidity of a chalk stream and occasionally displays the friskiness of a spring lamb. It also sports a most peculiar title which is certainly eye-catching but misrepresents the author’s treatment of the subject. Surely, the subject is sufficiently interesting not to need presentation in such a weird package. On the other hand, the study casts fresh light on radical popular culture in the early nineteenth century. As a study of ‘the radical underground’, it serves as a worthy companion and complement to Iain McCalman’s justly celebrated Radical Underworld (1988).

On the surface, Desmond’s study provides a sympathetic and substantial biography of William Devonshire Saull. But it also goes far beyond that. A rich London merchant, who traded successfully in French wines, Saull used the profits of his business to sustain the cause of freethought and to promote popular interest in science. He did so partly by funding radical movements engaged in condemning Christianity as a false religion. These movements were separately led by Richard Carlile and Robert Owen. The book covers the period from the 1820s to the death of Saull in the mid-1850s and is largely confined to London, Saull’s area of activity and influence. Saull’s contribution was not just as a financial backer of several radical causes but also as a public lecturer on geology and palaeontology and as the founder of a museum of ancient remains that eventually housed 20,000 exhibits, arranged in such a way as to propose that the biblical account of the creation, as found in Genesis, could not, on scientific grounds, be taken as true and therefore could not possibly be seen as divinely ordained.

Unlike other museums of the time which sought to entertain the upper classes in a milieu of genteel exclusivity, Saull’s museum was pitched at the people. No admission fee was charged and no membership was required. As well as founding a museum for the people, Saull was also involved with the establishment of popular educational institutions. These were likewise bent on exposing Christianity as a falsehood and clerical scam, notably the temples of reason associated with Richard Carlile in the 1820s and early 1830s, the halls of science associated with Robert Owen in the 1830s and 1840s, and the secular halls introduced by George Holyoake in the early 1850s.

[W]hat has survived [of Saull] mostly resides in spies’ reports preserved in the Home Office Papers, now housed in the National Record Office at Kew and only available on ancient microfilm.

All of this ensured that disbelief in the spiritual claims of religion (whether it took the form of Deism or Atheism) became the faith of a popular movement rather than what it had been up to then: the esoteric preserve of a few learned individuals. In this respect, there occurred a gradual but sure secularisation of society, notwithstanding the opposition of the priesthood and the existence of frequently enforced blasphemy laws.

All this Desmond explores with considerable brilliance: even more so because of the limitations of the surviving evidence that relate to Saull, who left no family papers, kept no diary, produced no memoir, and even, it would seem, failed to catalogue the contents of his magnificent museum, which disappeared shortly after his death and before anyone else could do the cataloguing. Carlile’s, Owen’s, and Holyoake’s radical activities were preserved in the journals and tracts that they published. Saull, in contrast, worked less openly. He frequently gave public lectures, but little account survives of their contents. His published writings, if blasphemous, came out anonymously. Consequently, what has survived mostly resides in spies’ reports preserved in the Home Office Papers, now housed in the National Record Office at Kew and only available on ancient microfilm. Commissioned by the government, these reports were attempts to nail Saull for blasphemy and therefore are highly suspect as reliable evidence. Nonetheless, Desmond ingeniously puts such tricky evidence to convincing use.

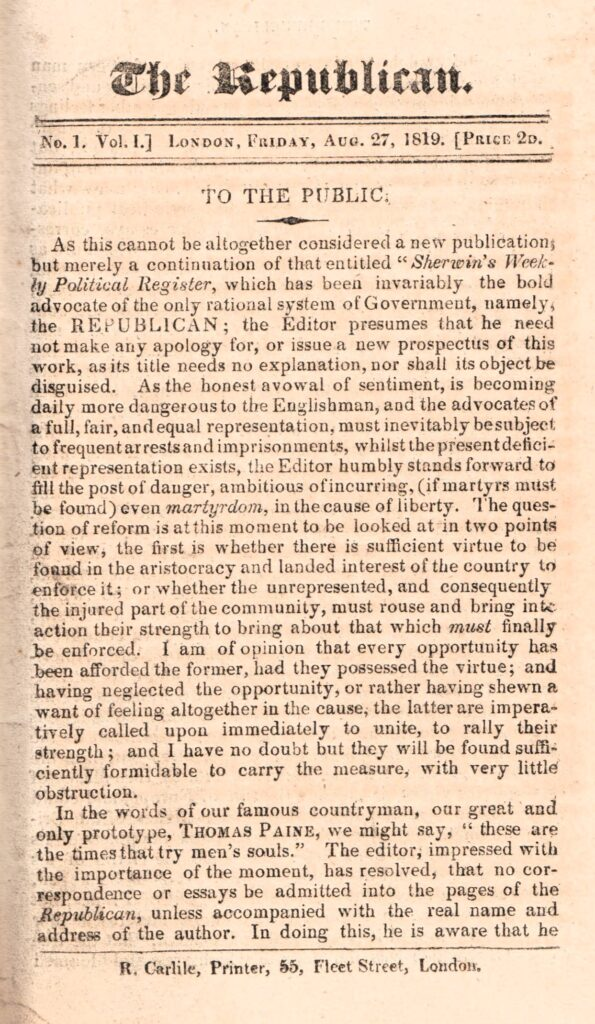

Otherwise, Saull’s activities, where he is named, have survived in newspaper reports that can be easily identified thanks to the digitised newspaper index. The danger with this method, however, is that one’s focus becomes too narrow; one can lose sight of the broader editorial intent and merit of the relevant newspapers. Consider Carlile’s weekly The Republican, which covered six years in the 1820s and ran to fourteen fat volumes. As well as being a vehicle for Carlile’s infidel republicanism, this periodical expressed the religious, political, and scientific views of Carlile’s considerable following, one that extended throughout much of the country, with concentrations of support not only in London but also in Manchester, Leeds, Edinburgh, Portsmouth, and Norwich. Yet Desmond brushes it aside as ‘a scurrilous rag’.

The author tends to play down Carlile’s importance in promoting the value of science, with next to no mention of his impressive tract Address to Men of Science (1821) and its advocacy of chemistry and astronomy as basic ingredients of any educational system. The same goes for Carlile’s role in shifting the focus of infidelity from Deism to Atheism, both through his own writings and by publishing and publicising the work of other Atheists, including Percy Bysshe Shelley and John ‘Walking’ Stewart. As for Saull, although assumed by Desmond to be an Atheist and implied as such in the book’s subtitle, he never appeared to label himself as one and therefore was, in all probability, a Deist. If so, he belonged to a tradition of infidel thought most famously associated with Thomas Paine and which, in the process of scientific discovery and secularisation, was probably more important than what an adherence to Atheism ever achieved

The highlight of the book appears in chapter eight and centres on a lecture given by Saull in Bristol in October 1833, the text of which was fully printed in Carlile’s final republican periodical, The Gauntlet. This lecture concerned the origins of man, seen not as a sudden act of divine intervention and design but as a cultural emergence from simian beginnings. Saull claimed to have taken the idea from the chemist Humphry Davy who, shortly before his death in 1829, wrote a strange memoir entitled Consolations in Travel; or, The Last Days of a Philosopher. In the book, Davy recounts a vision he experienced when seated alone in a moonlit Colosseum. The vision focused upon the emergence of man from a creature, incapable of fitting himself out with clothing and constructing a home, who dwelt naked in trees and caves and lived off wild fruit and succulent grubs. Inspired by this image, Saull told his audience of the connection between man and ape and its vital significance.

[Men] ‘must have been much more like a monkey than like a shorn and shaven and washed and educated man of the present day, with all his defects’ Richard Carlile and Robert Taylor

Saull was not alone in making the point and probably lied in attributing its sole derivation from Davy. By this time, apes were appearing in public zoos and the resemblance between orangutans and paunchy bishops seated in the House of Lords was too obvious to overlook. Carlile himself had remarked on the resemblance between men and apes ten years earlier in The Republican; he had picked up the point from the controversial materialist lectures Sir William Lawrence had delivered in 1816.

Later, in 1832, Carlile made the same point in lectures composed by himself with the aid of his friend the Rev. Robert Taylor and allegedly given by his mistress Eliza Sharples (Carlile was in prison at the time): men ‘must have been much more like a monkey than like a shorn and shaven and washed and educated man of the present day, with all his defects’. The animal linkage went down well with popular radicals who, many years earlier, had been memorably branded by Edmund Burke as belonging to ‘the swinish multitude’.

A second highlight appears towards the end of the book when Desmond discovers that housed in Saull’s museum were not only fossils and ancient bones but also the remains of recently deceased radicals, such as the skeleton of George Petrie and even the head of Julian Hibbert. This leads one to wonder what happened to the head of Richard Carlile, secretly detached from the rest of his body in 1843 and spirited away between death and burial. And what sort of stir was caused when Thomas Paine’s skeleton temptingly came up for sale in 1853 in a London auction house? Perhaps by this time Saull, who had not long to live, was too infirm to take action, or even notice.

The book is a treasure trove of information on a huge range of radicals, many, like Paine or Carlile, drawn from artisan backgrounds. As well as focusing on rich men engaged in promoting infidelity, notably Saull and Julian Hibbert (but no mention of Godfrey Higgins), the book offers biographical information on a number of poor and self-educated men who wrote scientific works of note, such as a former weaver from the north-west, Thomas Mackintosh, author of The “Electrical Theory” of the Universe: Or, the Elements of Physical and Moral Philosophy (1838), and Sampson Mackey, ‘the cobbler astronomer’ from Norwich, author of The Mythological Astronomy of the Ancients Demonstrated (1823-40). Then, there were the vitally important printers and publishers, such as the courageous James Watson, John Chilton, and Edward Truelove. All receive their due for extending the pool of knowledge upon which the anti-Christian cause was based, and Desmond provides a fascinating account of popular culture and its scientific affiliations.

Yet it remains to be said that all the eminent and durable discoveries of the time in the field of science were made by men who claimed to remain true to the Christian religion or, at least, not to be against it—in public, anyway. One thinks of Newton, Hartley, Priestley, Davy, Lyell, and Darwin: a measure of the authority that Christianity continued to exercise thanks to its social and political power and the accommodation great scientists had to exercise to secure recognition from the aristocratic and clerical establishment.

Altogether, The Reign of the Beast is an enthralling and useful Who’s Who, Where’s Where, and What’s What of popular science and radical infidelity in early nineteenth-century Britain (even if, as mentioned at the outset, it does rather go on). But please remember, if published in Saull’s lifetime, it would have led to several years in prison and probably the wrecking of his wine business through the imposition of heavy fines and the confiscation of its stock.

Related reading

The rhythm of Tom Paine’s bones, by Eoin Carter

Books from Bob’s Library series, by Bob Forder

Britain’s blasphemy heritage, by David Nash

How three media revolutions transformed the history of atheism, by Nathan Alexander

Charles Bradlaugh and George Jacob Holyoake: their contrasting reputations as Secularists and Radicals, by Edward Royle

Introducing ‘Paine: A Fantastical Visual Biography’, by Polyp, by Paul Fitzgerald

Christopher Hitchens and the long afterlife of Thomas Paine, by Daniel James Sharp

1 comment

A splendid review of a wonderful book, the result of a lifetime’s work researching and writing about the history of science, with a particular focus on the nineteenth century and the work of pioneering evolutionists.

The book is enthralling and given its length one is enthralled quite a while. As one who is fascinated by the radical lives and work of brave long nineteenth century radicals and freethinkers it has become clear to me how ‘alternative’ our history is and how poorly it is recorded compared to the mainstream, establishment orientated narratives. In that respect both Adrian Desmond and Michael Bush, among others, deserve our undying gratitude.

Both Bush and Desmond explain some of the practical difficulties they encounter as researchers, but I wonder if another reason why this history is relatively poorly documented is the challenge it is perceived to present to what might loosely be termed ‘an orthodox establishment narrative’?

Desmond writes about Saull’s ‘Museum of Evolution’ which existed before Darwin wrote a word. What is more, judging from his actions, Saull drew the materialist’s conclusion that Christianity was no more than a fiction that had developed to underpin society’s aristocratic superstructure and the privileges a hereditary elite drew from it. In consequence, Saull used his considerable fortune to sponsor the potentially revolutionary and freethinking activities of Richard Carlile and others. Darwin was careful to openly steer clear of openly drawing such dangerous conclusions. Now Darwin is celebrated as one of the BBC’s greatest Britons while William Devonshire Saull was totally forgotten. That is until the publication of this wonderful book.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate