Scroll down for the video of the interview itself.

One of the stereotypes of America is that it is a wasteland of gun violence, Bible-bashing, and hyper-capitalism—a vulgar place packed with reckless tycoons and inbred hillbillies. That this reflects some truth is sad. But sadder still is that this image obscures a greater truth: America is a nation founded on deep and radical philosophical roots. It was the first real instantiation of millennia of heretical, dangerous, and even atheistical ideas about the universe, human nature, and political order. Founded by learned sceptics both high- and low-born and embodying radical philosophy in its Declaration of Independence and Constitution, America is first and last a radical democratic republic. In its bones, it was and is a repudiation, and a containment, of orthodoxy and religion (as commonly understood).

Or so the philosopher Matthew Stewart would have it (and I agree with him). The radical atheism of America’s very soul is the subject of his revisionist book Nature’s God: The Heretical Origins of the American Republic (2014) and its sequel, An Emancipation of the Mind: Radical Philosophy, the War over Slavery, and the Refounding of America (2024). These books, alongside Andrew L. Seidel’s 2019 The Founding Myth and Gordon S. Wood’s 1991 classic The Radicalism of the American Revolution, encapsulate, in my view, the true America: the infidel, radical, internationalist, philosophical America. (Though it should be noted that Stewart and Wood differ in some fundamental ways, particularly on the role of—especially Protestant—religion in the American founding and early republic and the development of American democracy; here I am, as I am generally, on Stewart’s side.)

For Stewart, the American founding was inspired by ‘essentially atheistic and revolutionary’ philosophical ideas stretching back at least to Epicurus and wending their way through Giordano Bruno, John Locke, Baruch Spinoza, and many others: a secret thread of radicalism, often difficult to detect but very much present in the work of most of the great minds who made modernity.1 These ideas are not ‘Western’ in any special sense: they have appeared in many times and places. In 1776, this ‘radical philosophy’ erupted into view, was laid out in the Declaration of Independence, and changed the world forever. That this belies the common image of America as a pious country founded by religious refugees is appropriate, given that Stewart’s ‘radical philosophy’ is also an antidote to common ideas about life, nature, consciousness, and politics. Jonathan Rée’s Prospect review of Nature’s God captures the point well: ‘If this vigorous book wins the converts it deserves, then a new generation of patriots may rise up to celebrate the US not as God’s own country but as the oldest and greatest atheist nation.’

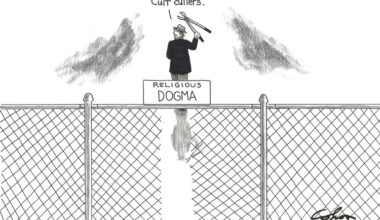

In An Emancipation of the Mind, Stewart argues that the original American Revolution was sunk under a counterrevolution led by slaveholding religious oligarchs until its ideals were revived by German radicals and infidels who sought refuge in America after the disappointments of 1848. Once more, Stewart dispenses with many comforting American myths, chief among them that the opposition to slavery was led by conscience-stricken Christians. In fact, the Bible was the very bulwark of slavery, and religion, by and large, was on the side of the enslavers rather than the enslaved; indeed, abolitionism was grouped by its enemies with such dangerous ideas as worker’s and women’s rights and considered a sure sign of infidelity.

Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln were freethinking radicals, and Lincoln borrowed many of his most famous lines from the now-obscure Theodore Parker, a man so unorthodox in his theology that even the Unitarians excommunicated him. John Brown, that great, wild, man, so apparently orthodox in his devoutness, had nothing but contempt for the pro-slavery churches and owed much of his political theology to the anti-slavery radicals, heretics, and infidels. (Later, Martin Luther King, Jr lifted his ‘arc of the moral universe’ line from Parker, and he, too, had to face down the champions of orthodox religion in his battle for civil rights.)

This second American revolution, or refounding, was followed by another counter-revolution, and this cycle has gone on to this very day. America is now in another phase of revolutionary/counter-revolutionary ferment. Trump and the Christian nationalists can trace their ancestry directly through the pious architects and defenders of Jim Crow, the godly slaveholders and slavery apologists, and even all the way back to the founding era when religious conservatives like Yale president Timothy Dwight complained of the godlessness of the US Constitution.

The great love I have for America is a love founded on the America of Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Paine, Thomas Young, Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the many other philosophical radicals discussed by Stewart. This America, which I think can legitimately be considered the true America, is the America that remains the best hope, both for itself and the world. America is multidimensional, or perhaps multiversal, in its diversity, but its core is discernible, and its core is radically heretical—nay, it is atheistic. America is an infidel nation—the oldest and greatest, to echo Rée.

Stewart’s books, as well as being astoundingly deep and wide in their erudition, are also beautifully written and structured. He grounds the high philosophy in the lives of the people who lived it: the uncouth Vermont revolutionary Ethan Allen, the German feminist Ottilie Assing, and the escaped slave Frederick Douglass, to name but a few. For Stewart, ideas matter in history. His books make genuinely exciting reading, both in their pursuit of a slippery and oft-misunderstood philosophical thread and in their tellings of the lives of a brilliant and oft-forgotten cast of characters. Incidentally, they also implicitly and explicitly (and devastatingly) refute the arguments of the New Theism2. Epicurean atheism: the core of civilisation. I was overjoyed to have the opportunity to talk to Stewart on 26 September.

Our conversation, in which the above and more are discussed in greater depth, can be viewed below.

- As an aside that has just occurred to me while writing, I wonder how one might fit, say, the ancient Indian materialists into this scheme. Were they proponents of radical philosophy, too? A book including the Indian materialists would fit nicely with Stewart’s wide ranging across time and space to find the roots of modernity (as opposed to simply giving up and pronouncing that some spurious notion of ‘Judeo-Christian values’ is the foundation). I suppose this is a suggestion for Stewart, and I shall just have to wait for him to get on with it!

A relevant quote from Emancipation:

‘[T]he partisans of both “disaster” and “glory” routinely suppose not just that some singular culture (variously, “Western civilization,” “Western thought,” or “Judeo-Christianity”) is responsible for the creation of every aspect of the modern world… [But] [t]he Enlightenment was a scene of intellectual conflict that drew upon utterly foreign cultures in the ancient world and in the New World to destabilize systems of oppression.’

I am now reminded of a nice definition of ‘western civilisation’ by Roosevelt Montás in his 2021 book Rescuing Socrates:

‘A large and porous cultural configuration around the Mediterranean Sea, with strong Greco-Roman roots, that served as the historical seedbed for the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, the Scientific Revolution, the Industrial Revolution, and much of what is called “modernity.” While the European continent figures prominently, the tradition incorporates defining elements from non-European sources like the Arab world, ancient Egypt and north Africa, and even the Far East.

Used in this way, the term simply describes an integrated tradition of learning, debate, artistic expression, and political evolution. But while it is an integrated tradition, it is by no means a monolithic tradition—in fact, one of its hallmarks is its internal contentiousness. It is a tradition rife with fissures, where overturning the past is preferred to venerating it. Key aspects of the modern world emerge from this tradition of contest and debate, loose and fractured as it is. The case for its importance in understanding our emerging global culture is overwhelming. The tradition matters not because it is Western, but because of its contribution to human questions of the highest order.’

And I can’t help but include a paragraph (one which I trust is relevant) from my Areo Magazine review of Rescuing Socrates:

‘In this insistence on the importance of universalism and truth, Montás reminds me of the great Trinidadian Marxist historian C. L. R. James, who unabashedly celebrated the western tradition and who, as the writer Ralph Leonard has put it, “understood that the Enlightenment, though conceived and initiated (for historical reasons, not genetic ones) mainly by privileged white European men, is the common property of all of humanity.” I wish that more of those who today claim the mantle of radicalism were as wise as Montás and James. Perhaps then the so-called culture wars would be less noisy, destructive and vacuous. They would also be more truly radical, for universalism has always been a radical position for a narrow-minded and tribalistic species such as ours.’ ↩︎ - I can’t help but add an excerpt from the final chapter of Nature’s God, from a larger section in which Stewart effortlessly dismantles the central claim of the New Theism—i.e. that religion is justified by utility (emphases added):

‘The problems [with this argument] on the logical front are much worse. When we really do believe in something, we say we believe in it because it is true, not because it is useful (even if it happens to be useful, as the truth usually is). So, when we say that we ought to believe in religion just because it is useful, we are also saying that there is no reason to believe it is true. What we really mean to say is that it is useful for other people—or for some imaginary version of ourselves that does not believe what we in fact believe. And if we try to salvage religion by claiming that it is not a system of belief in the first place but a set of practices, as many liberal apologists for religion are wont to do, all we are really saying is that these (other) people who practice it don’t know what they are doing. Utility never justifies belief; it can justify only deceit and delusion. Now, how can deceit or delusion be useful? Mostly, they are not. On occasion, they can be used for good ends—but only to the extent that they induce people to act in accordance with something else that we know to be true. In making such a judgment about the utility of a delusion, moreover, we necessarily presuppose that it would be better for everyone to do the right thing for the right reasons. Thus, once we begin to justify religion by utility alone, we have already committed ourselves to the view that the most useful thing to do with it is to diminish its use.’ ↩︎

1 comment

When an author has written two of my ten favorite books (I’ve read thousands), it gladdens me to learn that after ten years a new one is on the scene. I look forward to watching the interview.

While “Nature’s God” is my top favorite “The Courtier and the Heretic: Leibniz, Spinoza, and the Fate of God in the Modern World” is a gem as well. These books are deeply philosophical, very witty, and truly exciting.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate