Blasphemy, as I understand the word, is the action of demonstrating disrespect towards God. Asserting the non-existence of God is clearly blasphemy, as also are laughing at the accounts of God’s doings in the various books describing his fictional exploits, and at the dodgy human characters who inhabit them. Blasphemy has been perfectly legal in England and Wales since the obsolete common law offences of blasphemy and blasphemous libel were repealed in 2008. Nevertheless, in practice, it is still not allowed, at least not with respect to one particular belief system.

I am a physics teacher. I teach science, and, to be absolutely clear on this point, I object to both Islam and Christianity for the same reason: they are not true. The fact that those who believe in these religions do either good or bad things in response to their beliefs is entirely irrelevant to this view. I do not feel under any obligation to take any of their claims seriously nor to follow any of their rules.

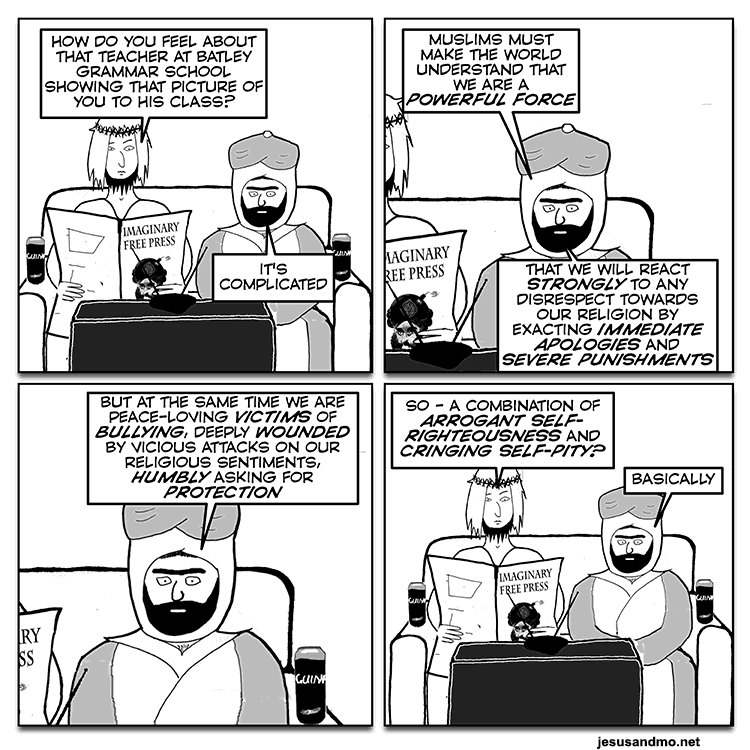

Back in March 2022, I was teaching physics at a prestigious and high-achieving English grammar school, a post I had held for fourteen years. During all of that time, I had used a coffee mug which features the characters ‘Jesus and Mo’, from the brilliant satirical cartoon of the same name. The characters are obviously supposed to represent Jesus, the (fictional) Christ, and Mohammed, the (spurious) Prophet. The cartoon’s format is to take some ludicrous aspect of one or other of the three Abrahamic religions—Moses makes an occasional appearance—and to have Jesus and Mo, and their sceptical interlocutor, Barmaid, reduce it to the absurdity that it is. I am a big fan of the cartoon and had bought the mug to show my appreciation. This mug of mine was kept on a shelf in the Science staff room and had been in full view of all my colleagues, and of any student who happened to be passing through, during my fourteen years at the school.

One afternoon break, when I was on playground duty and finishing a cup of tea, one of the children decided to take a covert photograph of me and my mug. The child then appears to have scuttled off to a local newspaper, and the next thing I knew, the story that a teacher at my school had used a mug with an ‘offensive image’ on it was in the national news.

What was the school to do? Nothing about the way that Jesus and Mo are depicted on the mug is remotely offensive, but everyone knew about the poor RS teacher still in hiding from Islamist thugs in Batley. The thugs had objected to the teacher using another cartoon of Mohammed in one of his lessons, so it was plausible to think that the mug incident might develop into a similar story. Personally, I had no inclination to hide from Islamist thugs nor to appease them, although I obviously did not want to put my family at any risk from the ‘Religion of Peace’.

In the event, the headmaster telephoned me on the day the story broke to tell me not to come in to work, and later that day I was told that I was suspended pending an investigation.

I followed the story both in the mainstream media, and on Twitter (as it then was). As far as I could tell, many comments in the online media were, apart from the usual virtue-signallers, broadly supportive of me, and disgusted that I had been suspended for something so trivial. The school took its time with the investigation and after a few days the story died away. I was emphatically told that I should not talk to the press, and also forbidden to contact any colleagues at the school. In the meantime I was being paid a good salary to sit at home playing my piano. On the advice of the police, I installed security cameras at my home—but Essex is not Batley, and I was never actually threatened.

In response to the school’s investigation, I replied that, if drinking tea out of my mug was a disciplinary offence, I would like them to take into account approximately three thousand identical previous offences, at which nobody had batted an eyelid. I also demanded to have my mug back, as I was not allowed on site and all my stuff was still there. After two or three weeks, I was reinstated. I was sent the mug by post, nicely packed in bubble wrap, and told that I was not allowed to use it at school. I was still forbidden to talk to the press and I did not see any public report of my being reinstated.

Why was I banned from using my ‘Jesus and Mo’ mug at school? I do not know. Whatever the official reason, however, the context in which the decision was made raises concerns about the ability of teachers to express themselves freely and lawfully on religious matters.

To be clear, while my experiences were related to the particular school I was teaching at, there is little doubt that the reactions of its management were typical for the times we live in. My story could just as well have happened anywhere in the UK.

I have not studied Islam in any depth, but I understand that in many mainstream interpretations of Islam, drawing particularly on the hadiths, Muslims are forbidden to make an image purporting to be of Mohammed, notwithstanding the fact that nobody knows what he looked like. Of course, not all people who claim to be Muslims will necessarily agree with this interpretation—including many Shia Muslims in Iran—but it certainly seems to be a popular position.

The reason given by some scholars is that images of Mohammed might lead Muslims into the heresy of idol worship, and so to thinking Mohammed is God, thus repeating the error that Christians supposedly make regarding their Jesus character. Apparently, Islamic scholars have a low opinion of the ability of ordinary Muslims to distinguish between God and a human prophet.

If you live in the UK, consider yourself to be Muslim, and agree with the ban on images of Mohammed, then you are entirely at liberty to refrain from drawing or owning pictures of Mohammed. Of course, in the UK you can, Muslim or not, draw anything you like (within some reasonable legal limits). Muslims may also eat bacon or drink beer, or not, as they prefer; in the UK religion is a choice. No adult or child is obliged to be a Muslim, nor a Christian, nor anything else.

The school, by banning me from using my mug, was in practice—whether or not this was the intention—enforcing Islamic rules on a non-Muslim, something which I find completely unacceptable.

However, what the more fundamentalist Muslims demand, and these are the ones I call Islamists, is that it is not only Muslims who have to follow Muslim teachings, but everybody else has to, too. Taken to its fanatical extreme, this type of intolerance has led to the murder of those who dare to manifest any sort of ‘blasphemous’ attitude towards Islam, such as Samuel Paty or the Charlie Hebdo journalists. The hypocrisy and double standards of the Islamist position are clearly demonstrated when one considers that while its adherents demand, and are allowed, halal meat here in the UK, in many institutionally Islamic countries, such as Iran or Saudi Arabia, alcohol (and bacon) is subject to severe restrictions or outright bans. Islamists in the UK demand that Muslim women be ‘allowed’ to cover their faces, but in the strictest Islamic countries, all women, Muslim or not, must follow Islamic modesty codes.

In short, those at the fundamentalist end of Islam demand—just as Christian authorities did in the past—that everyone must tolerate and conform to their religious practices and customs, but are not willing to extend the same toleration to those of other religions or none.

The school, by banning me from using my mug, was in practice—whether or not this was the intention—enforcing Islamic rules on a non-Muslim, something which I find completely unacceptable. My inoffensive, humorous, and perfectly legal mug was, under some interpretations of Islam, blasphemous. Thus, despite not being in breach of any English law, in practice it was banned from an English school, seemingly out of deference to an intolerant ideology.

The reaction of my school was, as I have suggested above, all too typical in these days of increasing Islamist influence in the UK. Cases such as the dropped Quran in Wakefield in 2023 and the Batley incident in 2021 show how reluctant school and public authorities in the UK often are to take firm action against Islamists, not least out of fear of incurring allegations of racism.

Indeed, defining so-called ‘Islamophobia’ as a ‘type of racism’ is a clever if cynical ploy on the part of Islamists—although they might consider that by linking a religion to a race they are arguably implying that Islam is itself a racist religion. Otherwise why is it to be assumed that anyone who claims to be a Muslim, or demonstrates ‘Muslimness’, is therefore a member of some particular ‘race’? Is someone who claims to be a Muslim not a true Muslim if they are from the wrong ‘race’?

But mine is not the progressive view increasingly adopted by, or enforced upon, the teaching profession, not just in one or two institutions, but across the board. The progressive view is that in the name of ‘tolerance’ we must all be mindful of the ‘distress’ that might be caused to a supposedly Muslim child if the beliefs of his or her parents are challenged in an educational setting. The truth is, though, that education necessarily involves having one’s assumptions and beliefs challenged. It is the parents who are more likely to be ‘distressed’ than their offspring—who, in my experience as a teacher, are generally much more open to new ideas.

The fact that in the main Islam is itself an intolerant and repressive ideology does not seem to feature in the progressive argument.

In order to avoid trouble on this issue—and other topics where dissent is perceived as wrongthink—ordinary people like teachers, who are generally speaking obliged to live on their pay and cannot afford to risk being sacked from their jobs, censor themselves. The few cases of teachers and other employees getting into trouble for speaking out serve to remind the more cautious that, unlike me, they are wise to self-censor.

So how, in a country where blasphemy is a non-event, should the school management have behaved? In my view, they should have told the press that my mug was perfectly legal, that it celebrated a valid critique of religion that any free citizen of a free country was entitled to support, that there was nothing inherently harmful about the way Mohammed was depicted, and that there was no case for any sort of disciplinary action. They could then have added that, regarding images of Mohammed, as I was not a Muslim I was not under any moral obligation of any sort to follow rules invented by Islamists. Isn’t that the kind of support which teachers should be able to expect from a school in a free and civilised country?

I had already decided that it was time to retire from teaching before the mug incident ocurred. I was fortunate in having reached an age where I could afford to do so. In contrast, any teacher with a similar outlook but at an earlier stage of his or her career must either keep silent or sign up to the groupthink.

This country is short of physics teachers. I wonder why?

Related reading

Blasphemy and violence: review of ‘Demystifying the Sacred’, by Adam Wakeling

Britain’s blasphemy heritage, by David Nash

On trial for blasphemy: the Freethinker’s first editor and offensive cartoons, by Bob Forder

10 years since the Charlie Hebdo attack: a message from the Freethinker, by Daniel James Sharp

Charlie Hebdo: An open letter to the free world from a freethinker, by Khadija Khan

The problem with ‘Islamophobia’, by Mark Lilly

Kant vs Tahir Ali: why desecration should not be outlawed, by Daniel Herbert

Image of the week: first edition of ‘The Satanic Verses’, by Daniel James Sharp

The Galileo of Pakistan? Interview with Professor Sher Ali, by Ehtesham Hassan

Islamic identity politics is a threat to British democracy, by Khadija Khan

Three years on, the lessons of Batley are yet to be learned, by Jack Rivington

The need to rekindle irreverence for Islam in Muslim thought, by Kunwar Khuldune Shahid

Is all publicity good publicity? How the first editor of the Freethinker attracted the public’s attention, by Clare Stainthorp

Silence of the teachers, by Nath Jnan

Secularism and the struggle for free speech, by Stephen Evans

Image of the week: Jesus and Mo on clerical fascism, by Mohammed Jones

Image of the week: Jesus and Mo on identity, by Mohammed Jones

Jesus and Mo: Christmas cartoon 2022, by Mohammed Jones

Cancel culture and religious intolerance: ‘Falsely Accused of Islamophobia’, by Steven Greer, by Daniel James Sharp

Image of the week: ‘Moses Getting a Back View’ (1882), by Daniel James Sharp

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate