Books From Bob’s Library is a semi-regular series in which freethought book collector and National Secular Society historian Bob Forder delves into his extensive collection and shares stories and photos with readers of the Freethinker. You can find Bob’s introduction to and first instalment in the series here and other instalments here.

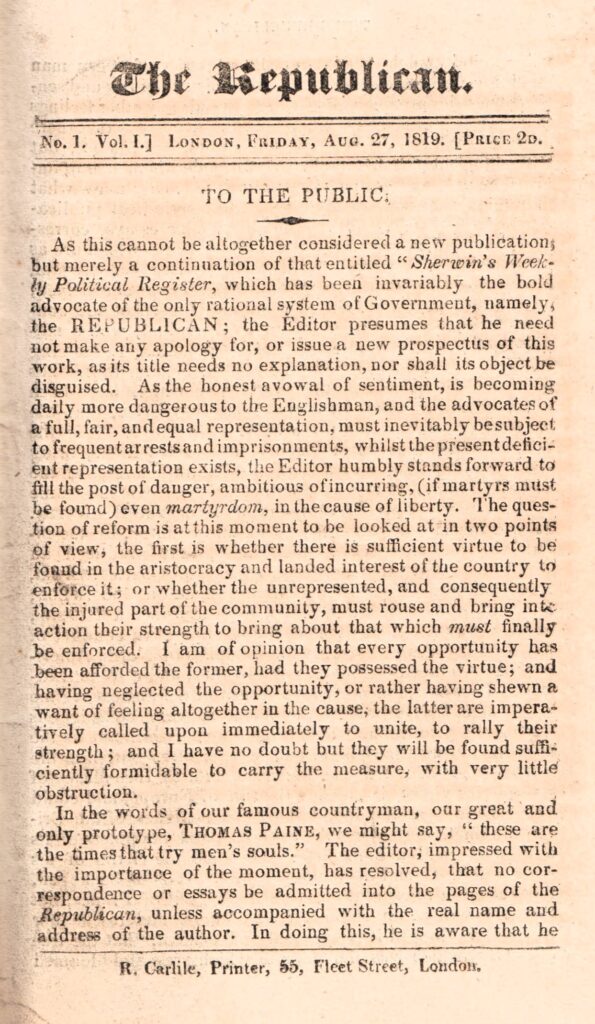

Of all the items in my library, one of those I prize most is a bound volume of the first twenty issues of Richard Carlile’s The Republican, a radical journal which appeared weekly from 27 August 1819. It thrills me that I can peruse the original leaves of a journal edited and largely written by one of the bravest and most steadfast freethought heroes in British history. At a time of ferocious oppression in the wake of the Peterloo massacre, Richard Carlile dared to challenge the authorities and their arbitrary power in the most outspoken terms—all while he was being tried for blasphemous libel for publishing Thomas Paine’s works, including Rights of Man and The Age of Reason (the subjects of the first two articles in this series).

Richard Carlile was born the son of a shoemaker on 8 December 1790 in Ashburton, Devon. From the age of twelve, he served an apprenticeship as a tinsmith. By 1813, Carlile was in Gosport and probably worked in the nearby Portsmouth Dockyard. On 8 December of that year, he married Jane Cousins. At this time, he was attending David Bogue’s academy and was in training to be a missionary (Bogue was a Congregationalist and from his academy sprang the London Missionary Society). Of course, Carlile was to change his mind about the virtues of Christianity, but his theological training was to stand him in good stead.

Soon after their marriage, the Carliles moved to London and, after struggling to make a living as a tinsmith, Carlile began to sell pamphlets on the streets, including those of Thomas Paine. By 1817 he was reprinting cheap editions of Paine’s works, including The Age of Reason, which had not been sold legally in Britain since 1797.

Peterloo

On 16 August 1819, the then-biggest-ever meeting of working-class people was held in Manchester. Carlile travelled with the main speaker, Henry Hunt, to St Peter’s Field and was on the platform when the yeomanry charged, killing eighteen and wounding many others. Carlile avoided arrest and returned to London to publish one of the first accounts of what he termed the ‘Manchester Massacre’ in the journal he edited, Sherwin’s Political Register. The following week the journal’s title was changed to The Republican, thus upping the stakes. Carlile did not mince his words: in the first issue of the retitled journal, in an article entitled ‘The Crisis – No. 1’ (clearly, he was mimicking his hero Thomas Paine), he wrote:

‘The massacre of the unoffending inhabitants of Manchester, on the 16th August, by the Yeomanry Cavalry, and Police, at the instigation of the Magistrates, should be the daily theme of the press, until the MURDERERS are brought to justice by the Law Officers of the Crown, under the instruction of the executive, or in default thereof, until the People have obtained their proper rank and station in the legislature…’

To Dorchester Gaol

This was all too much for the authorities, and Carlile was soon on trial for blasphemous libel, as well as for publishing two classic deist texts: Paine’s The Age of Reason and Elihu Palmer’s Principles of Nature (1801). He referred to this as a ‘mock trial’ because he refused to accept that the law could suppress free discussion and because the judge refused to allow him to call the Archbishop of Canterbury and Chief Rabbi as witnesses. He did, however, grasp the opportunity of reading the whole of The Age of Reason to the court so that it was published as part of the record.

Carlile was convicted in October 1819, sentenced to a total of three years in prison, and fined £1,500 but, as he refused to pay the fine, he was not released until November 1825. He was sent to Dorchester Gaol, well away from his radical colleagues and sympathisers in London, and placed in solitary confinement for fear he would contaminate other inmates. He was supposed to be taken from his cell for half an hour each day for exercise, but he objected because this would have meant his being paraded before the other inmates. As a result, he didn’t leave his cell for three years.

On the other hand, his cell was light and airy and he had his own sofa, sink, water closet, and bath. There was also a writing desk from which he continued to contribute to and edit The Republican, now published by his wife Jane. This writing desk is currently in the Conway Hall Library. In those days, prisoners could pay for better food and accommodation and Carlile had some well-heeled supporters, including Julian Hibbert, a wealthy Caribbean sugar plantation owner. One thing that the authorities seem to have missed was that the Dorchester to London stagecoach passed both Dorchester Gaol and the Carliles’ premises at 55 Fleet Street, thus providing a convenient service which Carlile used to deliver copy to London. The Republican sold well due to the notoriety of its editor and he produced twelve volumes while in prison. It was during this period that he pronounced himself an atheist (rather than a deist), the first person in England to do so during his own lifetime.

In 1820 it was Jane’s turn to be tried. She stood in the dock with her baby, Thomas Paine Carlile, in her arms. She was sentenced to two years and shared her husband’s cell. When in prison, Jane gave birth to a daughter whom she named Hypatia, after the pagan philosopher who was torn to pieces and burnt by a Christian mob in the fifth century CE. Jane’s place in Fleet Street was taken by Richard’s sister, Mary, who in turn received a sentence of six months and joined Richard and Jane in the same cell in Dorchester. Meanwhile, more than 150 men and women, Carlile’s ‘shopmen’, were sent to Newgate Prison for selling The Republican.

Despite all this, Carlile’s freethought books continued to sell. To make the authorities’ task more difficult, they were sold from behind a screen. On the customer’s side was a clock face bearing the names of the items on offer with a hand that could be pointed at the relevant title, whereupon a hidden shop assistant pushed the book through a hole in the screen, thus avoiding identification. Carlile called it ‘selling books by clockwork’.

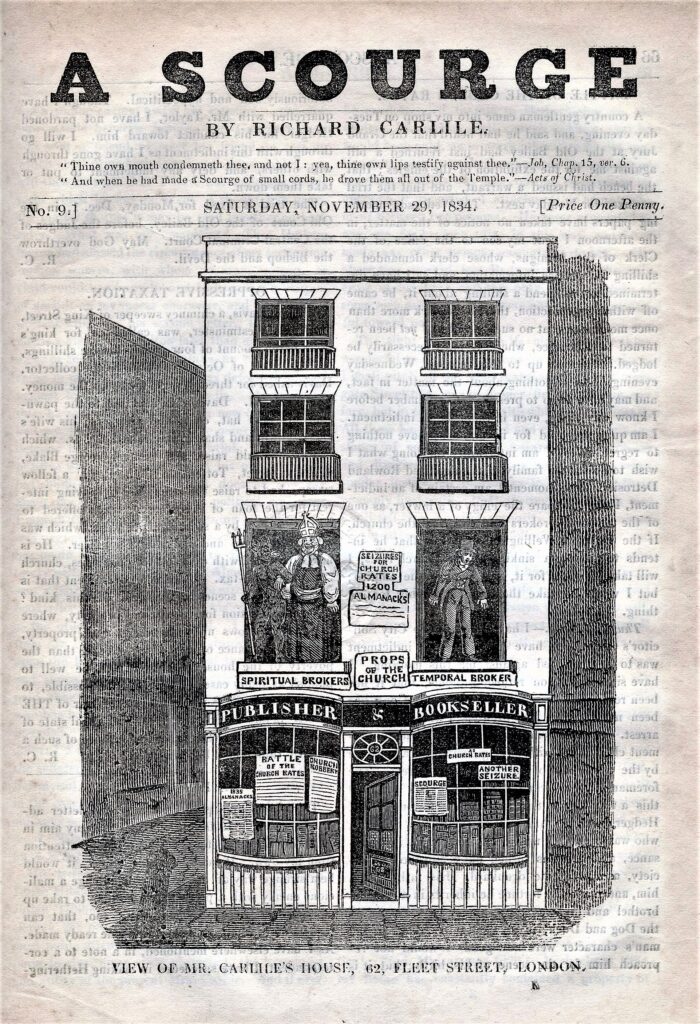

By 1825 it had dawned on the authorities that their actions were merely promoting the Carliles’ publications. Carlile was suddenly and unconditionally released. He returned to London, took out a lease on larger premises at 62 Fleet Street, and expanded his business. These premises are still standing today—although fast food, rather than books, is now sold from them.

Every Woman’s Book

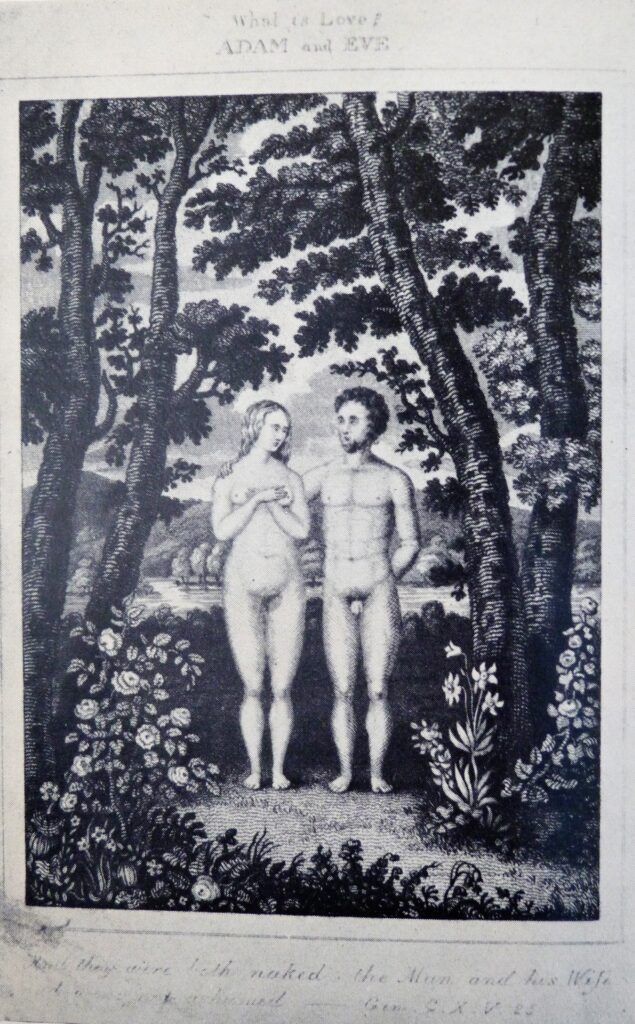

In 1826 Carlile wrote and published Every Woman’s Book, the first book to advocate birth control, provide contraceptive advice, and advocate free love in Britain (it had been preceded by an article in The Republican entitled ‘What is Love?’). For Carlile, contraception served two purposes: it helped prevent conception and facilitated…pleasure!

‘See, what a mass of evil arises from bastard children, from child-murder, from deserted children, from diseased children, and even where the parents are most industrious and most virtuous, from a half-starved, naked, and badly housed family, from families crowded into one room, for whose health a house and garden is essential. All these matters are a tax upon love, a perpetual tax upon human pleasure, upon health, a tax that turns beauty into shrivelled ugliness, defaces the noble attitude of mankind, and makes its condition worse than that of the cattle of the field.’

Carlile was appalled by the practices of abortion and infanticide, both common at the time. He suggested that no married couple need have more children than desired and maintained that no unhealthy woman need endanger her life through childbirth. He believed that there need be no illegitimate children and that sexual intercourse could be independent of the dread of conception.

Carlile’s feminist views were rooted in his experience at Peterloo, where many peaceful women were present, and in witnessing the sacrifices made by his female shop workers, particularly Jane and Mary. Now he went a step further, arguing that Christian sexual morality was a constraint on female emancipation and reduced women to subservience. He accused Christian marriage of causing men to treat their wives ‘with as much vulgarity as he treats any other chamber utensil’ and for placing women under a form of ‘legalised slavery’.

To hammer his point home, Carlile included a frontispiece illustration to his book showing Adam and Eve without the usual fig leaves. He was making the point that, in his opinion, aspects of the Bible were obscene—far more obscene than his endeavours to improve people’s lives.

For Carlile, lovemaking was physically and mentally healthy, and he challenged still more taboos by claiming that women found sex as pleasurable and satisfying as men. His favoured contraceptive method was the sponge, although he also mentions ‘the glove’ (or condom) and withdrawal.

Carlile must have been disappointed by the reaction to his book. Many of his female followers turned against him and William Cobbett branded him ‘the grand pornographer and pimp’who planned to lure into prostitution the maidenhood of England. Nevertheless, the book sold steadily.

Lecture tours

When Carlile was released from gaol he went on four lecture tours, two in 1827 (totalling eight months), one in 1828 (six months), and another in 1829 (also six months). Although these had mixed success, they did help to establish a national network of reformers. He was always particularly well-received in Portsmouth and Manchester, although he had substantial support in many other industrial towns. He was not a particularly forceful speaker, and his most successful tour was the 1829 one, when he teamed up with Robert Taylor, the ‘Devil’s Chaplain’, and launched an ‘infidel…missionary tour’.1 Taylor was a Cambridge-educated former Anglican Minister who had served a prison sentence for blasphemy. His oratorical skill greatly exceeded Carlile’s.

Eliza Sharples

Sadly, Richard and Jane were now falling out of love, and Richard took up with Eliza Sharples in 1832. Sharples became, in his words, his ‘moral wife’. She was a formidable character and campaigner in her own right, an effective platform speaker who edited her own feminist journal, The Isis. Years later, after Carlile’s death, a young Charles Bradlaugh was to briefly find a home with Sharples when his relationship with his father broke down.

The Rotunda

In 1830, Carlile opened the Blackfriars Rotunda on the banks of the Thames, near Blackfriars Bridge. This was a substantial building with two lecture theatres, one of which could accommodate up to 1,500. The Rotunda became infamous as the centre of reformers’ activities at a time of mounting discontent.

In 1831, Carlile was incarcerated again, this time in London, for defending the ‘Swing Riots’, uprisings by agricultural workers demanding better working conditions. Now it was Sharples who visited him in prison. During one of her visits, they conceived a child, the first of four. While he was imprisoned, Sharples took over management of the Rotunda.

Final years

After this second imprisonment, Carlile’s career declined. Financially bereft thanks to government fines, he had also lost a lot of support due to his abandonment of Jane, though he had granted her an annuity of £50 per year. He also made himself unpopular with many former supporters by adopting the title Reverend. His atheism was unwavering, but he thought Christianity provided a sound moral code.

Carlile’s end was probably hastened by his belief (shared by others) that swallowing a small amount of mercury each day improved health. He died on 10 February 1843 and his body was taken to St Thomas’s Hospital where, in accordance with his wishes, his brain was dissected for research. He was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery.

The Republican provided a foundation on which Richard Carlile built his reputation and following. His punchy, colourful, sometimes outrageous writing reflects his audacious and extraordinarily courageous war against arbitrary authority in the cause of liberal, democratic, and Enlightenment ideals. Can you blame me for gently handling my bound volume with awe—and a misty look in my eye?

Main sources

Joel H. Wiener, Radicalism and Freethought in Nineteenth-Century Britain. The Life of Richard Carlile. Greenwood Press, 1983.

Michael L. Bush, The Friends and Following of Richard Carlile. A Study of Infidel Republicanism in Early Nineteenth-Century Britain. Twopenny Press, 2016.

Michael L. Bush, What is Love? Richard Carlile’s Philosophy of Sex. Verso, 1998.

- Editor: I can’t resist adding a little more about Taylor’s nickname. One of Carlile and Taylor’s stops on the infidel tour was Cambridge, where a young Charles Darwin witnessed the controversy stirred up by the two infidels. Perhaps this was what made him fearful, years later, of stirring up controversy by publishing his theory of evolution by natural selection. He certainly remembered Taylor’s nickname, writing in 1856 ‘What a book a Devil’s Chaplain might write on the clumsy, wasteful, blundering low & horridly cruel works of Nature!’. In 2003, a latter-day missionary of Moloch, Richard Dawkins, was inspired by Darwin to entitle an essay collection A Devil’s Chaplain (albeit erroneously crediting Darwin with coining the term—which, in fact, goes as far back as Chaucer). ~ Daniel James Sharp ↩︎

Related reading

The rhythm of Tom Paine’s bones, by Eoin Carter

From the archive: ‘A House Divided’, by Nigel Sinnott

Charles Bradlaugh and George Jacob Holyoake: their contrasting reputations as Secularists and Radicals, by Edward Royle

Britain’s blasphemy heritage, by David Nash

Freethought and birth control: the untold story of a Victorian book depot, by Bob Forder

How three media revolutions transformed the history of atheism, by Nathan Alexander

Secularism is a feminist issue, by Megan Manson

Review of ‘A Dirty, Filthy Book’ by Michael Meyer, by Bob Forder

Is all publicity good publicity? How the first editor of the Freethinker attracted the public’s attention, by Clare Stainthorp

On trial for blasphemy: the Freethinker’s first editor and offensive cartoons, by Bob Forder

What should schools teach young people about sex? by Peter Tatchell

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate