One winter morning, I found myself on the doorstep of a suburban-style house in Larne, County Antrim, Northern Ireland. Larne, an unprepossessing industrial conurbation on the coast, some 30 miles from Belfast, is mostly known for its ferry service to nearby Scotland.

The house I had arrived at rather grandly announced itself to be named ‘The Oratory’. It possessed two doorbells, one of which was accompanied by a hand-written sign indicating that the bell was not working. The other bell, however, proved to be similarly inactive. Eventually, knocking loudly on the door produced a response in the form of the sounds of rustling and shuffling and bolts being undone. Clearly, the inhabitant of this unusual dwelling was concerned with security. Then, a short, pale-faced, autumnal-looking, priestly character appeared from the shadows beyond and ushered me into a dimly lit hallway, then further into a large, book-lined, ramshackle room scattered with religious accoutrements.

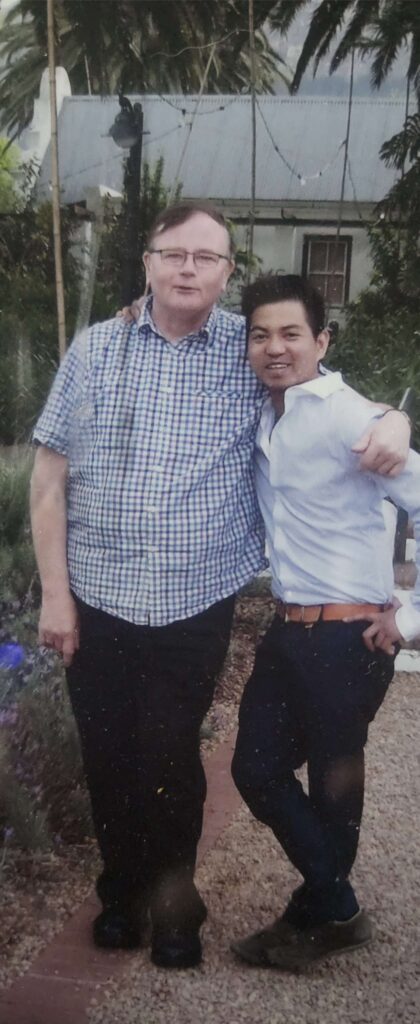

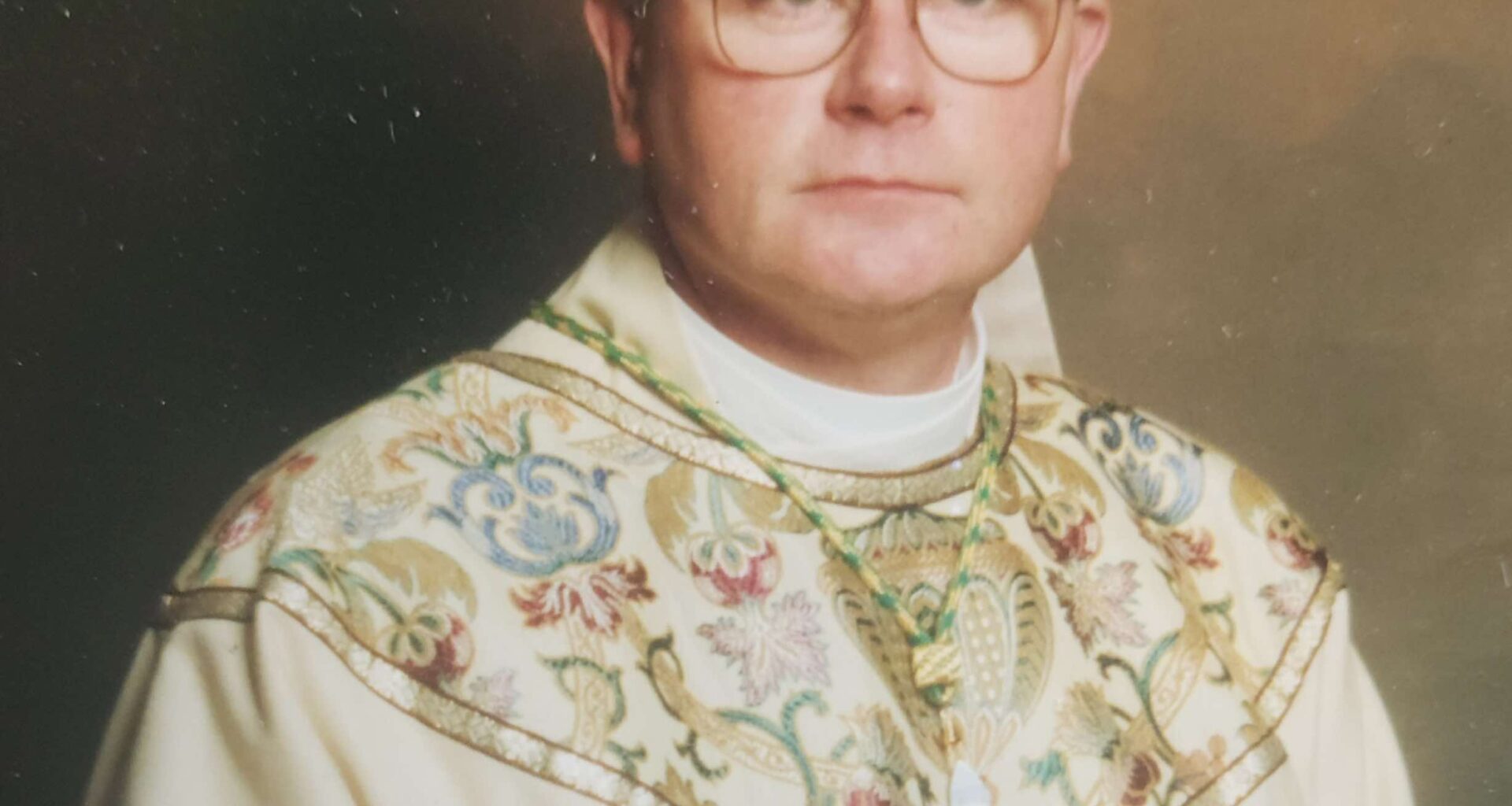

Clerical robes were slung over the back of a dining chair, a ponderous sideboard featured a drinks cabinet, and a bay window was occupied by a large table which functioned as a desk—one laden with a sprawling disorder of papers. A small electric fan heater perched precariously aboard a teetering heap of books fought a battle against the chill air. As a researcher working on an LGBT+ history project in Belfast, I had been granted an audience with Bishop Pat Buckley, rebel priest, theologian, and controversial blogger, in the house where he lived with his husband, Eduardo Yanga. Buckley had been one of the more unusual religious figures in late twentieth-century Ireland. There was little about his career which could be considered conventional.

The Early Years

When Pat Buckley told me his story, I knew that it was one which had been recounted and elaborated upon many times before, including in two published autobiographies. The bishop was, after all, a public figure, and one who, more unusually, claimed that his life was an open book, the contents of which were habitually presented as a struggle against adversity.

Patrick Buckley was born in Tullamore, County Offaly, the Republic of Ireland, in 1952, the son of a trade union official father and homemaker mother. For the rest of his days, he spoke with the broad and sonorous tone of the Irish Midlands. The land of his youth was a pious and austere one dominated by the Catholic Church. That Buckley was the eldest of seventeen children, six of whom died either at birth or not long after, speaks volumes to the grim reproductive regime of Irish Catholicism.

From childhood, Pat wanted to be a priest, having ‘fallen in love’ with the religious atmosphere of his local church. Foreshadowing his career, Buckley’s journey to ordination was not straightforward—having first dropped out of secondary school, he later returned to college and progressed to a seminary in Dublin which he described to me as having been like a ‘kind of jail with five-star cuisine.’ In his 1994 autobiography, A Thorn in the Side, Buckley recalled enduring a deeply weird interview with the seminary’s patron, John Charles McQuaid, the forbidding Archbishop of Dublin. McQuaid, apparently, was in the habit of asking new students, over tea and cake, whether they knew the ‘facts of life’, and following this up with a detailed exposition. Sex, wrote Buckley, was a big preoccupation in this celibate empire. His issues with authority other than his own (he denied, unconvincingly, that this was the case) eventually resulted in his expulsion. He then entered a different seminary in Waterford, finally becoming a priest in 1976.

Activist Priest

Buckley was initially employed in Bridgend, in South Wales. Here, in what would become a recurring theme of his life and career, he clashed with other priests, finding them impossible to live with, and returned to Ireland. After a few months of drift, he wound up in Belfast, where in the summer of 1978 he was posted to a parish in West Belfast which included the Divis Flats on the Falls Road. These had become synonymous with violent conflict and social problems. Pat said arriving there was like walking onto the Moon. The Troubles were at their height, and the flats were, he told me, in ‘terrible condition’, resulting in a ‘situation of total hopelessness.’

Eventually, he started doing something unconventional. He began to brush the streets on his own. Locals were, apparently, initially horrified that a priest, whose hands were supposed to be ‘anointed’, might do manual labour, but by the end of the week, a popular movement to clean up the area had begun. His social activism made Buckley popular—and much in demand—but he was hated by the priests he lived with, who he accused of living in luxury and ignoring social problems. Eventually, he was moved to a rural parish outside Kilkeel in the Mourne Mountains. Subsequently concluding that he had been suffering from PTSD after his experiences as a priest in Divis, Buckley was disconcerted to find himself in the silence of the countryside. He told me that he again became involved in activism, tussled with local loyalists, and was quickly moved. He was called for a meeting with Bishop, later Cardinal, Daly. ‘The bishop called me in and told me: “I’m moving you to Larne as your last chance. When you go to Larne, I want you to lie low. I don’t want to see your head above the ocean.”’ Larne was seen by the bishop as an unattractive location, and the posting as a punishment.

Pat Buckley’s head soon appeared above the ocean. Larne was a town where 80% of the population were Protestants and Catholics suffered discrimination from one of the main employers, the power station. For speaking out in public against this, and doubtless other points of contention, Buckley was, in 1986, finally sacked by Bishop Daly. At this point, his story becomes more unusual. He refused to accept that he was suspended from his duties as a priest, nor did he accept a financial incentive to move to Australia. He also refused to leave the parochial house. While engaged in his well-publicised dispute with Daly, he began holding services in the house where he lived. The services grew in popularity, and Buckley created his own church by combining two rooms into one, which he called the Oratory.

As a liberal priest who operated outside of the formal structure of the Catholic Church, Buckley quickly became a popular provider of weddings, especially to the divorced, who the Catholic Church would not marry. Couples were frequently referred to him by priests in other parts of Ireland. In fact, Buckley’s independent ministry resulted in Larne being claimed as Northern Ireland’s wedding capital in the early 1990s. Describing him as a ‘one man wedding machine’, The Sunday Life, a tabloid newspaper, reported in 1993 that between 200 and 250 couples were being wed by him per year. Buckley was quoted as saying that at the height of the wedding season in 1992, he married thirteen couples in one week. He characterised his ministry as being for the ‘outsiders’. Buckley visited prisons, counselled the homeless, and was much preoccupied by the plight of women who had been in secret relationships with priests, revelling in the role of unofficial chaplain to Ireland’s liberal or alienated Catholics. In 1998, Buckley became a bishop in controversial circumstances. He was consecrated by another renegade cleric, Dr Michael Cox. The Catholic Church viewed this advancement as ‘valid, but illicit.’ It resulted in both men being excommunicated.

Sexuality

Pat Buckley explained to me how his sexuality had been a cause of torment and misery to him as a young man. The Ireland of his youth was harsh and unforgiving towards gay men, with male homosexuality criminalised in Northern Ireland until 1982 and in the Republic until 1993. An understanding of same-sex desire as a sickness was commonplace in the Republic in the 1960s and 1970s, and initially, Pat believed that he was ill (for more details on this, see my forthcoming article ‘Between Sin and Sickness’ in Irish Historical Studies). His training as a priest emphasised ‘how horrible the whole thing was’, while as a teenager, he had suffered a mental breakdown during which he was hospitalised but felt unable to tell doctors the cause of his difficulties.

Consequently, Pat told me how he had ‘persisted in mental agony about my sexuality’ until he was in his mid-thirties. By this point, he had been officially dismissed from the Catholic Church and decided that if he was no longer bound by their rules, then he could begin rethinking his sexuality. He underwent five years of psychotherapy, and one day, he told me, ‘I stood on the streets of Belfast and for the first time in my life, I felt the freedom of a son of God. I could be a priest, I could be Catholic, could be gay, and I could have love in my life.’

Pat became involved with the LGBT+ movement in Belfast. This began in the late 1980s, when he ministered to gay Catholic men who were dying of AIDS, a harrowing experience during which he was dressed ‘like a spaceman’. At a funeral, he met PA Maglochlainn, a teacher and gay rights activist who was a fellow dissident Catholic. Maglochlainn introduced him to both the gay Christian movement and the Northern Ireland Gay Rights Association. At the same time, Buckley remained closeted until the late 1990s. Interestingly, his 1994 autobiography made no reference to his homosexuality. It was telling of social conditions in the province during the 1990s that while Buckley’s career as a religious dissident received plenty of publicity, his sexual identity was hidden and separated from his public image.

He eventually came out in 1999, apparently in response to a tip-off that a newspaper was about to run a story about his private life. Pat Buckley was a pioneer in marrying same-sex couples as early as 2001, although these unions had no standing in the law at the time. In 2010, it was Buckley’s turn to get married; he announced his impending civil partnership to his boyfriend, Eduardo Yanga. Eduardo subsequently occupied the unusual position of being the only known legally recognised same-sex spouse of a Catholic priest in Northern Ireland.

Later Years

Pat Buckley remained charismatic, and I found him both likeable and a fount of knowledge on the social history of LGBT+ lives in Northern Ireland. It was a memorable experience to hear his stories of rebellion and queer resilience in this odd little enclave of ultra-liberal Catholicism on the edge of Ireland. At the same time, I sensed that Buckley’s glory days were well behind him. The antiquated environs of his house brought to mind some kind of religious museum. In the even chillier bathroom, framed satirical cartoons of a younger Buckley running rings around Bishop Daly kept company with an ancient nineteenth-century toilet.

And I knew, but did not want to mention, that his reputation had been severely compromised in more recent years. Without a salary from the Church, Buckley was dependent on income from conducting ceremonies. Demand for weddings had presumably decreased since the heady days of the early 1990s, as Irish Catholics became less attached to Catholicism, yet he continued to minister to those who wished for a religious ceremony yet were unlikely to be accepted by mainstream churches. His reliance on ceremonies made him vulnerable to exploitation. Just how dangerously so was revealed in 2013, when he was convicted at Belfast Crown Court for having officiated at fourteen sham marriages intended by those participating in them to be used to flout immigration laws. Defence counsel stated that their client was motivated by compassion and initially saw nothing wrong with the marriages; only later did the frequency of the weddings make their purposes obvious. Buckley maintained that he had conducted the weddings in good faith. He received a three-year suspended sentence, narrowly avoiding prison after his deteriorating health was taken into consideration—as well as suffering from Crohn’s disease, it was revealed that he was HIV positive.

His reputation, so carefully projected in his autobiographies, was further besmirched by his outspoken blog. This was a clunky enterprise which aimed to uncover corruption and dysfunction within the Catholic Church; it featured anonymous open comments which frequently gave view to a bitchy and unhinged-sounding religious subculture. I had spent some time, wide-eyed, investigating and hoaking through the blog. Contained within it were Buckley’s attempts to ‘out’ priests he believed to be gay, as well as harshly worded diatribes against various enemies. He thought that sexually active priests were ‘hypocrites and pretenders’ for disobeying their promise of celibacy and that there was no room in the Church for sexually active gay clergy. He even asserted to me that he believed that priests traded sexual favours for professional advancement. His attempts to out gay priests, were, one newspaper commented, bizarre. Doubtless, Buckley would claim that he himself had remained celibate until sacked by the Church. I found it difficult to square the angry blogger with the pleasant elderly theologian who served me tea and biscuits.

Bishop Pat Buckley died in his sleep on 17 May 2024, aged 72. Although living with serious illnesses, Buckley did not seem obviously unwell when I visited him a few months prior. When I left, he was gearing up for his second interview of his day—‘for a documentary on Independent Catholicism’, I was told (‘It’s bigger in the States’). News reporting showed that being dead had not immediately affected the bishop’s capacity for controversy. Plans for a public funeral were abandoned after a campaign by mysterious online enemies which featured homophobic smears. In the months that followed, Eduardo, who had previously avoided publicity, emerged as the defender of his partner’s legacy and reportedly plans to contest attempts by the Church to repossess the Oratory.

Ultimately, Buckley was a deeply complex man. He loathed the Catholic Church yet remained unhealthily drawn to and fascinated by it. He loved Catholicism, which conspicuously extended to clerical titles and the grandiosity and campy pomp of its ceremonial garments. He revelled in publicity and was a staple of tabloid newspapers. Confident of the influence of the supernatural in his life—he claimed in his autobiography to have once been thrown to the ground at Lourdes by an invisible and malevolent force—Buckley was, as he told me, probably one of the few priests to be a member of the National Secular Society.

Ostensibly a man of peace, he was attracted to and animated by conflict, proudly showing me how his grant of ecclesiastical heraldry featured the heads of three bulls symbolising struggle. He was hardly the only veteran of the struggle for gay liberation to have adopted eccentric or downright odd opinions in old age. One conspicuous manifestation of this was his belief that orgasm might permit a momentary glimpse of the divine. As he related to me,

As Christians, when we die, we see God. The beatific vision, you know, when you see God, you can’t explain it, it’ll be so pleasurable. It’s a beatific vision. And I think that the orgasm is a kind of forerunner of the beatific vision. I say it in that book, ‘Even Atheists at that moment say: “Oh God!”’

Note: unless otherwise indicated, quotations from Pat Buckley come from the author’s interview with him, conducted in February 2024. Other details are either referenced in the text or are from Buckley’s 1994 memoir A Thorn in the Side.

1 comment

A very interesting article, thank you for researching Buckley and bringing his story to light. I remember the blog very well, it was a very evil and unforgiving space where angry priests shared gossip about their confreres. I was glad when it disappeared.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate