Introduction

An expert on human rights might seem to be an unlikely target for censorship by a British university. Yet this is what happened to Steven Greer, emeritus Professor of Human Rights at Bristol Law School and a fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences and of the Royal Society of Arts, in the years leading up to his retirement in 2022. As reported by the Free Speech Union and elsewhere, in October 2020, the president of the Bristol University Islamic Society (BRISOC) complained to the authorities that Greer’s module on ‘Islam, China and the Far East’, on the Human Rights in Law, Politics and Society (HRLPS) unit, was ‘Islamophobic’. In February 2021, despite being warned not to go public about a matter still under investigation, BRISOC set up an online petition that featured a photograph of the professor next to a sign saying ‘Stop Islamophobic teaching’.

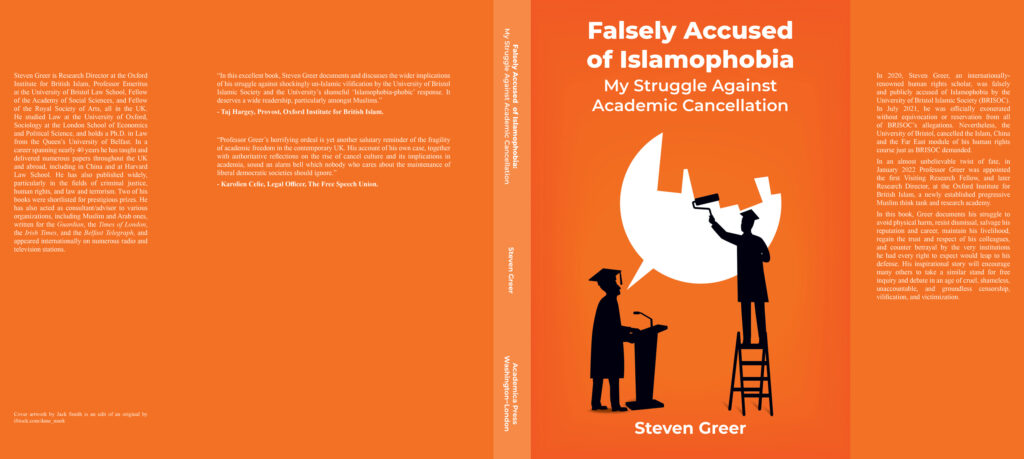

In July 2021, Greer was cleared of all allegations after an independent enquiry lasting five months. Nevertheless, he claims, some of his colleagues in the Law School effectively prevented him from teaching the module again in the last of his thirty-six years there. Moreover, ‘Although the complaint [against Greer] was not upheld,’ as the university publicly admitted, the latter also ‘recognised BRISOC’s concerns and the importance of airing differing views constructively.’ Greer argues that the university’s conduct ‘sent a clear signal’ that he was ‘guilty of Islamphobia in spite of having been officially exonerated.’ His latest book, Falsely Accused of Islamophobia: My Struggle Against Academic Cancellation, which contains a full record of his ordeal, was published by Academica Press on 13 February 2023.

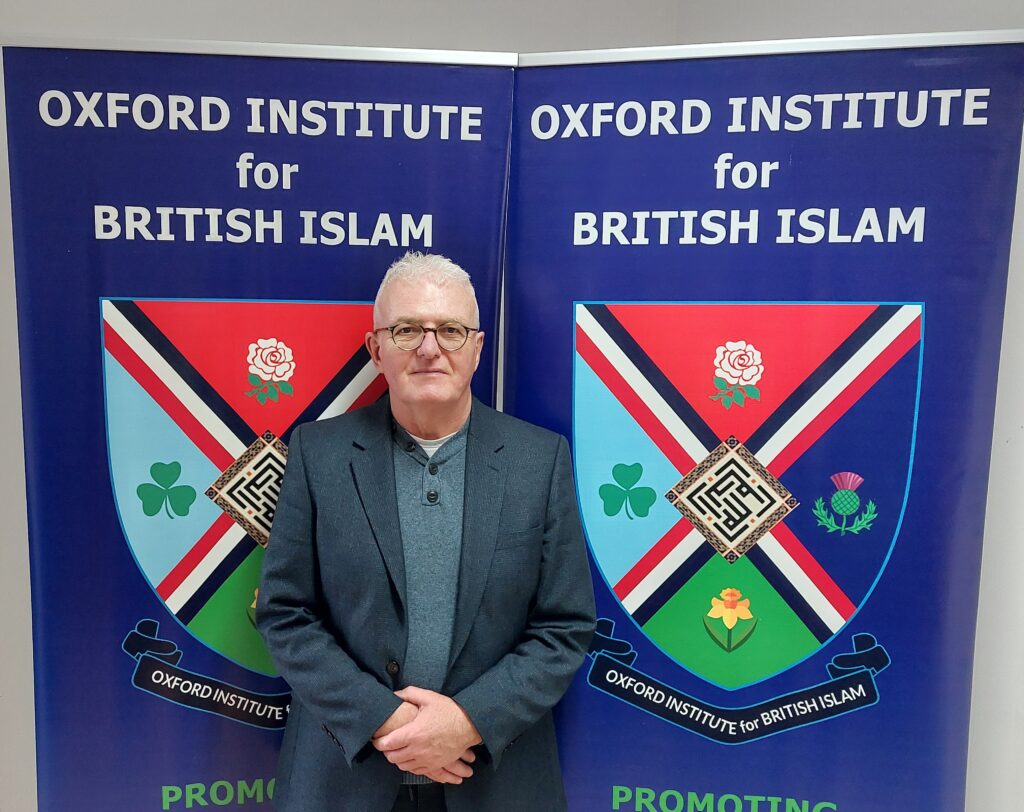

In January 2022, as a direct consequence of the BRISOC scandal, Greer was appointed to a non-stipendiary Visiting Research Fellowship at the Oxford Institute for British Islam, a fledgling UK charity whose stated aim is to develop ‘an authentic Islam that is rooted in and relevant to life in 21st century Britain…and which has taken on board the useful nuances and good personality of British life and culture without compromising any of the fundamentals of the faith.’ He later became OIBI’s Research Director.

I met Greer over tea in Piccadilly, London. In the interview which follows, he talks to me about the origins and course of the campaign of vilification against him, including its allegations of Islamophobia, and his response. We explore the reasons for the failure of his fellow academics and Bristol University to defend his right to responsible scholarly discussion about Islam.

Greer also looks back on his youth in Belfast during the Troubles, his early research into counter-terrorism in Northern Ireland, and his assessment of Prevent, the UK government’s controversial counter-extremism strategy after 9/11. Finally, we consider two knotty problems: how Islam can be best integrated into and accepted by modern British society, and how we in the UK can move beyond the polarising mindset of the culture wars.

~ Emma Park, Editor

Interview

Freethinker: Do you have any religious or spiritual beliefs?

Steven Greer: I would describe myself as a freethinker – one who inclines towards classic liberal values: human rights, democracy, rule of law, and open markets with a touch of Oriental mysticism and Buddhism. I have a sense of the spiritual, if you like. But my interest in Buddhism is open-ended – it is more about contemplation and meditation. This is possible without endorsing its finer points, except perhaps for the basic ideas of impermanence and insubstantiality.

Could you tell us a bit about your background and where you grew up?

I come from Belfast and grew up in a very devout, liberal Methodist family. My parents were not very political and were uncommonly anti-sectarian. I suppose that gave me the opportunity to think for myself. I went to a state grammar school. Looking back on that, the thing I value most was that our teachers also encouraged us to think for ourselves.

Today, would you see yourself as Irish or British?

I am British-Irish or Irish-British – I have had both passports for decades. That was another thing that was unusual in my upbringing, because my father in particular always insisted that we recognised our Irish identity. It has become fashionable recently for more Protestants in Northern Ireland, and people further afield, to claim Irish citizenship, particularly because of Brexit. I was ahead of the game. However, I am proud of both my British and Irish identity, and I recognise the strengths and flaws of each. In both cases, there have been negative and positive elements.

What are your research interests?

My research was initially motivated by my experience of growing up in the Troubles, which blighted my teenage years. There were gangs roaming the streets, you could easily get caught up in fights, and you could be blown up or shot at a moment’s notice. I was very perplexed by this: why was it happening? How had I ended up in such a dysfunctional society? I yearned to find out more. I studied law at Oxford from 1976-79, but I was disappointed by it intellectually. It was very dry and limiting. Then I went to the LSE to study sociology, and then back to Belfast for a PhD in counterterrorism law.

I ended up writing a book about the ‘supergrass’ system in Northern Ireland: a series of trials in the 1980s on the evidence of informants, which was deeply controversial on both sides of the sectarian divide. It was one of the few things that, in the counter-terrorist framework, both Loyalists and Republicans vehemently objected to, partly because they were very worried about it decimating their ranks. It may well have done. But it did so in a way that was difficult to defend by any credible conception of civil liberties and the rule of law: there were not enough legal controls, there was little corroboration, and it all happened in a non-jury context.

My intention was to have a career that straddled law and sociology. But there were more jobs in academic law than sociology. I was initially obliged to teach traditional legal subjects. In the mid-1990s, however, the law school at the University of Bristol was mildly criticised in a teaching review for not having a human rights course. So I said, ‘I’ll do that.’ It was not until 2005 that I had the first opportunity to design a unit that fully coincided with my interests. This was a socio-legal or social science course, which I called ‘Human Rights in Law, Politics and Society’, and which provided a platform from which to observe global current affairs through the lens of human rights, or vice versa.

Where does the study of Islam fit into all of this?

In the post-Cold War context of 2005, in addition to western liberalism, the two biggest kids on the block were political Islam, which had been on the rise since the Iranian Revolution in 1979, plus China and the Far East. Islam, China and the Far East are ideologies or a ‘geopolitical spaces’ which offer self-conscious alternatives to Western liberalism. The fact that there was a rapidly expanding literature about human rights in all these contexts made it possible to add a module on Islam, China and the Far East to the HRLPS course, which I then taught without incident for 13 years.

The fact that I have served the University of Bristol productively and faithfully for 36 years makes my experience all the more bitter. I had some of the best students in the law school – the more reflective and more thoughtful ones who wanted to look over the legal parapet and see the lie of the land beyond. Many of them were Muslim. Nobody had any issue with the unit or module whatsoever until, almost out of the blue, the University of Bristol Islamic Society (BRISOC) decided everything I had been saying about Islam was Islamophobic.

It is important to separate the intellectual debate about Islam and human rights from the scandal that developed. BRISOC lodged a complaint with the University in October 2020 without bringing it before any of the law school’s half a dozen or so informal mechanisms first. It was signed by the president of BRISOC, a medical student, who was ostensibly acting on behalf of anonymous students, but who had never attended my course himself.

Ultimately, after a vitriolic campaign by BRISOC on social media, and after a senior academic at the University of Bristol had investigated my conduct, in July 2021, I got a very gratifying email saying I had been completely exonerated of all charges [see a fuller account in Greer’s conversation with the Bristol Free Speech Society, and in his book].

However, I was told I was not allowed to tell anybody except my family and close friends until I, the university, and BRISOC had drafted a joint statement, which never happened. There was then the question of what I was to teach in my last year before my retirement in 2022. I wanted to deliver the topic on Islam, China and the Far East again, to prove that I had been vindicated. But two junior colleagues, who were due to take the unit over, decided to remove the module from the syllabus, precisely for the reasons the enquiry had rejected. This decision was immediately approved by the Law School. I then went on sick leave for three months because there was no way I could have gone back into the Law School with a cloud like that hanging over my reputation and integrity.

In October 2021, after BRISOC had unsuccessfully appealed against my exoneration, the University issued its final public statement, which said, ‘the complaint has not been upheld…[but] we recognise BRISOC’s concerns and the importance of airing differing views constructively.’ It also said that my course had been altered to respond to the new conveners’ ‘wish to deliver the material in a context that is both broad-reaching and respectful of sensitivities of students on the course.’ I was absolutely furious because, in spite of my exoneration, this statement made it look as if I had been let off on a technicality, and that there might have been substance to BRISOC’s complaint after all. This was not only a smear on my reputation and integrity; it compounded the risk that BRISOC’s campaign posed to my physical safety.

When my sick leave ended, the Law School and the University also declined to authorise my return to work and in fact obstructed it.

Did your two colleagues who decided to cut your module give reasons for their decision?

I was told expressly in an email that it was to avoid further complaints and to prevent ‘othering’ Muslim students. This was, of course, totally in defiance of my exoneration.

What were BRISOC’s charges against you?

They claim that everything the authoritative academic literature says about Islam, particularly about Islam and human rights – which is all I was discussing in the class – is Islamophobic.

Let me give you an example. It is universally accepted that in its early history, the Islamic faith spread very rapidly through war and conquest in the first instance, driven mostly by material motives – power and booty, basically. And then it stabilised through trade and conversion. Within a few decades of Mohammed’s death, a huge Muslim empire had been established extending from the shores of what is now Portugal to the Himalayas. BRISOC claims that to make such an observation is Islamophobic. Yet there is not a scholar or historian who knows anything about the history of Islam anywhere in the world who would dispute it. BRISOC also claims that it is Islamophobic to observe that traditional Islam does not regard men and women as truly equal. Yet, according to the Qur’an, a man can have four wives, but a woman can have only one husband. That is plainly unequal. On divorce, children also typically go to the husband, and not to the wife.

What was BRISOC’s response to these points?

They have no answer. That is precisely the point. And it graphically illustrates the current crisis of academic ‘cancel culture’: the people who want to take their opponent down through vilification and victimisation do not want to engage in debate about the substance of the issues themselves. They just want to say, ‘You are a racist, Islamophobe, transphobe, etc. – because you have said things we do not like, that we think are Islamophobic, transphobic, homophobic, and so on.’ But if you ask them to tell you why something you have said is Islamophobic, their response is, ‘We are not going to tell you – it’s just the way it is.’ There is no debate. If we had had a debate I could easily have demonstrated how ignorant BRISOC is about the history of their own faith.

What is your view about using cartoons of Mohammed as a teaching aid in a lecture theatre at a university? Have you ever done so, or would you have done so?

No. It is obviously very dangerous. There is a huge risk even if, like the unfortunate US Art history teacher Professor Erika Lopez Prater, you take great care and only show representations of Mohammed painted by a highly respected medieval Muslim scholar for devotional reasons. Professor Lopez effectively lost her job for doing so.

We seem to be in a strange situation where academics and university administrators who are not Muslim are themselves suppressing people who want to discuss Islam. How have we got into this situation?

Fear – of two kinds. One is the fear of some kind of violent reprisal. But I do not think this is the dominant one. The most prominent is the fear, on the part of university administrators, of being seen as hostile to a minority, Muslims in my case, and of losing income from students as a result. It is as brutal as that. We have not used the term ‘woke’ in our conversation yet. But that is what it is.

On the subject of ‘woke’, what is your experience of the ‘culture wars’ and ‘cancel culture’ at university?

What the University of Bristol has done to me is a classic example of ‘wokeism’ and cancel culture. It is based upon many of the classic features, for example, the attitude that ‘we must be so concerned for and so sympathetic to (certain) minorities that they can never be criticised for wrongdoing. Whatever they say, whatever complaints they have, must be taken at face value and those who have offended them must be sanctioned.’ That is exactly what happened in my case. The university’s attitude seems to have been, ‘BRISOC was offended by your teaching and although you were cleared of wrongdoing we are still going to bend over backwards to placate them, we are going to take the module off the syllabus and you are effectively going to be frozen out for the remainder of your career.’

The ‘remainder of my careeer’ happened to be a very short time span. But had I been a younger man, less well advanced in my career, it would have been much more costly for me to have taken the stand I did. In fact, I probably would not have done so. I probably would just have capitulated myself.

Whose opinion are university administrators worried about?

They seem to be most worried about the opinion of angry militants and their supporters on the illiberal or ‘regressive’ left who dominate the social sciences, humanities, law and the arts in British universities. I have seen this perspective gain currency over the course of my career. As a result, I am no longer sure where I am now myself on the political spectrum. I spent most of my adult life on the centre left. I was, for example, a member of the Labour Party for 30 years, until I left in 2013, when I saw the leftward direction the party was taking.

I think that, in British universities, there has been a drift over the past decade or more, towards greater extremism, less tolerance, a greater willingness to vilify and victimise opponents, and to regard them as enemies rather than colleagues with a different, though legitimate, point of view. When I first arrived at Bristol, most of the staff were centre left politically, but academically conservative. But without my fully realising it, the whole institution has been shifting further and further towards the left, particularly over the past decade or so. Colleagues whose views were centre-right were squeezed out of the Law School. Life was made so uncomfortable for them that they moved elsewhere.

You might have thought of the tradition of Western scholarship in all fields, humanities and sciences, as being about the disinterested pursuit of knowledge – that this should be the ideal of liberal education. How do academics today who are so far on the left reconcile their dogmatic views with this idea of disinterested scholarship? Or do they not think that such a thing exists anymore?

Since they will not engage in these debates, it is difficult to say. But I think, from reading the literature and from what I know about some of my own former colleagues who are on that wavelength, that they view ‘disinterested scholarship’ as itself an obstacle to the ‘liberation’ of those oppressed minorities whose ‘emancipation’ they seek to facilitate.

Are the academics themselves in these oppressed minorities?

Sometimes, but usually not. Typically, they are people who regard themselves as the ‘allies’ of putatively subordinate or oppressed groups, and who are trying to fight their battles for them. One of the grievances I have with this is that, quite often and quite plainly, people who belong to these so-called ‘oppressed minorities’ do not subscribe to the political profile that the ‘wokes’ want to impose upon them. The ‘wokes’ want them to be angry, hostile and aggressively asserting a sectional identity. They do not want them to integrate. And anyone who belongs to such a minority but does not subscribe to this ideology is simply regarded as a traitor to the cause.

Take my case, for example. One of the questions it raises is why it happened when it did. One of the triggers seems to have been that I am a vocal defender of the government’s Prevent counterterrorism strategy. The people who regard me as their enemy had been trying to discredit me for this reason for some time. In 2018, some colleagues from another university denounced me and one of my Bristol colleagues on twitter as racist and Islamophobic because we publicly defended Prevent. Another of my own Bristol colleagues then jumped on the bandwagon and retweeted the denunciation, adding that we were suffering from ‘white psychosis’. We complained to the Law School, arguing that it should not tolerate one of its own staff falsely denouncing other colleagues as racist and Islamophobic, and endorsing a demand that they be sacked as unfit to work at any academic institution. Nothing was done about it. The colleague in question is still in post and has, in fact, since been promoted.

Is there any evidence that the Prevent strategy has increased Islamophobia?

No. The reason is that hardly anybody knows about it. The activists are hyper-aware of it. But the general public, including Muslims, generally have not heard of it.

The other thing that has happened in academic life, which is a source of great dismay to me, is the prostituting of social science. What I mean by this is that social science has become a vehicle for prejudice. Studies are being conducted and published which have no scientific credibility. Typically, those involving surveys do not employ random sampling but are driven by a self-selected group of people who tend to share the objectives of those who have conducted the survey. So the entire exercise is constructed in a manner which confirms the prejudices of the researchers.

One of the few randomly selected surveys about public attitudes towards Prevent found, for example, that very few Muslims knew about it. That knocks on the head the claim that Prevent is turning Muslims into a suspect community, and fuelling Islamophobia.

The reasoning of the anti-Prevent movement is also a classic exercise in illogicality. The argument goes like this: ‘Prevent is Islamophobic and racist. Therefore, anyone who denies that it is Islamophobic and racist, must themselves be Islamophobic and racist.’ Any logician would tell you that this is a logical fallacy, because the premise – that ‘Prevent is Islamophobic and racist’ – is precisely what is at issue.

You could argue that there are many logical fallacies in the ‘woke’ approach.

Yes – it is based on prejudice. The tragedy is that it warps something that is actually, on a more sensible interpretation, very worthy. Like many, I am in favour of social justice, inclusivity, diversity and equity in the academy and everywhere else, but not on ‘woke’ terms. However, according to the ‘wokes’, if you have a conception of social justice that differs from theirs, you are the enemy and part of the problem, not part of the solution. Therefore, you have to be silenced, not debated with.

The Oxford Institute for British Islam is a young organisation. Could you tell us a bit about it?

The Provost and originator of the OIBI, Dr Taj Hargey, originally from South Africa, is the imam of the Oxford Islamic Congregation. He wants to promote a liberal and progressive version of Islam globally, and particularly in Britain. His wife, Dr Jacqueline Woodman, is a Unitarian Christian and gynaecologist. The idea behind OIBI is to establish a think tank and research academy that can study and debate Islam in the UK and promote a liberal conception of the faith. I was originally invited to become OIBI’s first non-stipendiary visiting research fellow and later became its first Research Director.

The profile and position Muslims have in Britain is primarily for them to determine. But those of us who are not Muslim should help them to address this challenge in a way that is positive for everybody. Muslims have the prime responsibility to deal with the issues of Islamism, jihadism and the threat of terrorism, because only they can authoritatively demonstrate their inconsistencies with any legitimate interpretation of Islam.

What is the future of Islam in Britain?

Religions can be both forces for good and for bad. The key lies in how they are interpreted and what is done with them. Islam is no exception. The message of the Oxford Institute is that Islam takes on distinctive forms according to the environment in which it is found.

Like Christianity?

Yes. Therefore the challenge for organisations like OIBI is to try to mould both Islam and its environment – a kind of autopoiesis or symbiosis. The precise details are matters for negotiation, consideration and reflection.

Muslims are here in this country to stay. They are our neighbours and friends. Nobody could seriously think, and it would be terrible if they did, that they should be expelled as Jewish people once were. The challenge is to ensure they manage to live here in a way that is decent, fair, makes them feel at home, and contributes to society in a way that we can all appreciate and understand. A particular feature of this challenge is to find ways of persuading younger Muslims that they can have an authentic Islamic faith and still be part of Western liberal democratic society.

How can we in Britain move beyond the polarisation of the culture wars?

One of the lessons I have learned from my own, very sour experience is that when people try to shut you down, you should respond by saying more, not less. But finding ways of doing so can become more difficult as a result.

See also: Daniel Sharp reviews Greer’s book.

1 comment

Excellent interview Emma. It always amazes me why people get so upset when exposed to views they don’t agree with and respond by wanting to cancel or bar people expressing such views. If I hear views that I don’t like or don’t agree with I don’t want them barred, I don’t feel upset, I just feel a need to argue my case. It’s good exercise and I might even learn something new. I would have thought students particularly should ignore their hurty feelings and come up with well argued counter views, that’s what university education is all about.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate