As the UK prepares to elect a new government on 4 July, this seems a good moment to reflect on Charles Bradlaugh’s heroic stand for democracy against the religious reactionaries of his day. Bradlaugh, the founder of the National Secular Society (NSS) and an open atheist, was prevented by bigots from taking the parliamentary seat he was elected to represent and was subsequently imprisoned for insisting on his democratic right to do so. Emma Park, in the New Humanist, tells the story:

‘At the time, MPs were required to swear an oath of allegiance to the monarch on the Bible. Quakers were allowed to affirm, but they were the exception. Bradlaugh asked to affirm on the grounds of his atheism. A select committee decided, by one vote, that he was ineligible. He then tried to take the oath, but before doing so, wrote an over-confident letter to The Times in which he declared that the oath included “to me . . . words of idle and meaningless character”. As Bradlaugh’s biographer, Bryan Niblett, has shown, this merely encouraged those who disliked his atheism to argue that the oath would not be “binding on his conscience”. Others feared that, as a republican, he would not be loyal to the Crown.

In June 1880, Bradlaugh was told by the Speaker of the Commons that he was allowed neither to affirm nor to take the oath. Bradlaugh, in his own words, “respectfully” refused to withdraw, on the grounds that it was “against the law” for Parliament to prevent a properly elected MP from taking his seat. After a dramatic vote, in which only seven MPs supported him, he was arrested by the Serjeant-at-Arms and spent the night in custody in the Clock Tower beneath Big Ben – the last MP ever to do so.

Between 1881 and 1884, Bradlaugh was elected three more times in Northampton. It was not until the fifth attempt that he was finally allowed to take the oath, in January 1886. By this time, the stress of the campaigns, combined with legal and financial worries, was affecting his health. He would only live for another five years before dying of kidney disease and heart failure at the age of 57.

His story is a blot on Parliament’s record: a clear case of the abuse of political power fuelled by prejudice. It demonstrates the importance of having a constitution in which everyone’s right to “speculative opinions” is respected, and in which, equally, there is no stigma attached to the free criticism of others’ ideas.’

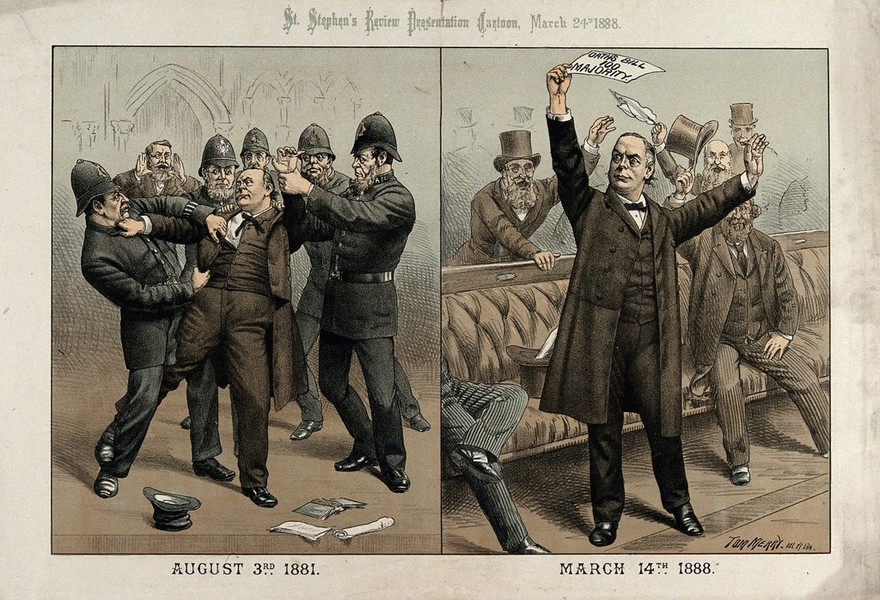

Though the struggle shortened Bradlaugh’s life, he triumphed in the end with the success of his campaign to enact the Oaths Act in 1888, which gave MPs the option to make a secular affirmation rather than swearing to God when taking their parliamentary seats. The lithograph above tells Bradlaugh’s dramatic story in two parts: from prisoner of conscience to victorious champion of democracy. Today, indeed, a bust of Charles Bradlaugh stands proudly in the halls of Parliament itself.

As the 2024 election looms, it would be well to bear in mind the central lesson of Bradlaugh’s struggle: freedom is never granted, it is always fought for. And that fight is far from over, even in an advanced democracy like the UK’s. After all, we still have an established church and a hereditary head of state (both of which were also opposed by Bradlaugh). The story of the struggle for democracy in Britain, which goes back as far as the 17th-century Levellers if not much further, and which takes in Thomas Paine, the Chartists, the suffragettes, and numerous others—well, that story is very far from over.

Further reading

Bradlaugh’s struggle to enter Parliament, by Bob Forder, NSS website

Charles Bradlaugh and George Jacob Holyoake: their contrasting reputations as Secularists and Radicals, by Edward Royle

Image of the week: Charles Bradlaugh’s study after his death, by Walter Sickert, by Bob Forder

Review of ‘A Dirty, Filthy Book’ by Michael Meyer, by Bob Forder

‘I do not think you are going to get a secular state without getting rid of the monarchy’: interview with Graham Smith, by Daniel James Sharp

Is all publicity good publicity? How the first editor of the Freethinker attracted the public’s attention, by Clare Stainthorp

Freethought and birth control: the untold story of a Victorian book depot, by Bob Forder

On trial for blasphemy: the Freethinker’s first editor and offensive cartoons, by Bob Forder

From the archive: imprisoned for blasphemy, by Emma Park

Secularism and the struggle for free speech, by Stephen Evans

What secularists want from the next UK Government, by Stephen Evans

Islamic identity politics is a threat to British democracy, by Khadija Khan

‘This is not rocket science’: the Disestablishment of the Church of England Bill 2023, interview with Paul Scriven by Emma Park

The case for secularism (or, the church’s new clothes), by Neil Barber

Blasphemy and bishops: how secularists are navigating the culture wars, by Emma Park

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate