Books From Bob’s Library is a semi-regular series in which freethought book collector and National Secular Society historian Bob Forder delves into his extensive collection and shares stories and photos with readers of the Freethinker. You can find Bob’s introduction to and first instalment in the series here and other instalments here.

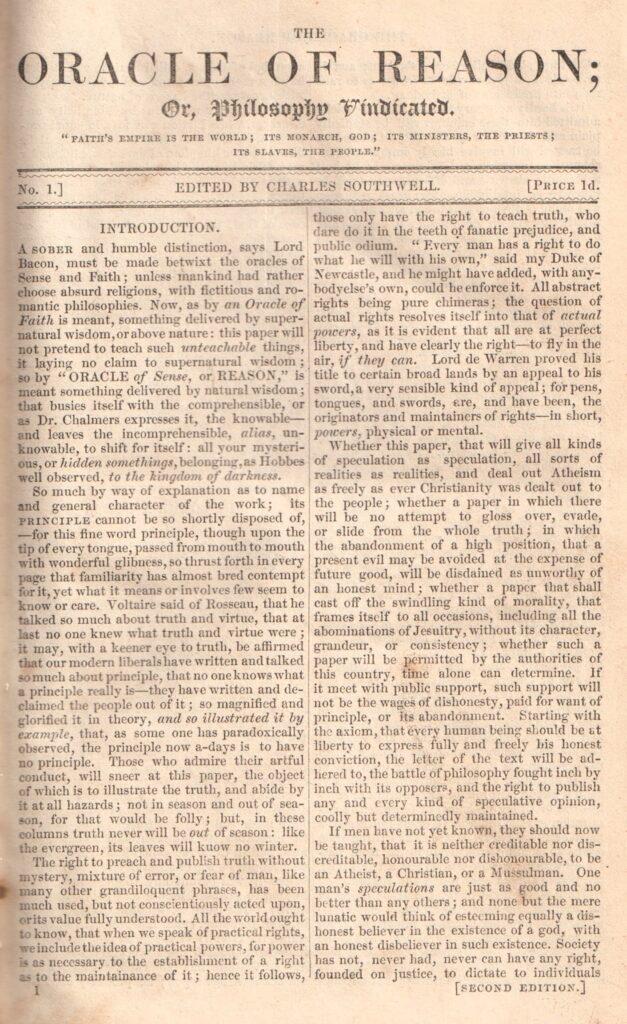

On 6 November 1841 the first issue of Charles Southwell’s The Oracle of Reason; Or, Philosophy Vindicated appeared. Some have claimed that this was the first atheist journal, although Edward Royle is more cautious, stating in his Victorian Infidels (1974) that what set it apart ‘was not its message but its language.’ To the best of my knowledge, it was the first to aggressively proclaim its atheism. Whichever way you look at it, the journal was to cause quite a stir and was to prove to be of seminal importance in determining the careers of some militant freethinkers and defining the battlelines between them and the authorities for years to come.

The Oracle was to last just over two years, and I am fortunate to own one of two bound volumes of the journal; my volume comprises the first 52 approximately weekly issues plus two supplements and records of the related trials of George Jacob Holyoake and Charles Southwell. There is an index and a preface by one of the Oracle’s editors, Thomas Paterson. The cloth binding is contemporary, sturdy but worn, with stained boards and faded gilt titles which give little clue to the treasures contained within. These items are scarce, to say the least, and it is very unusual to find the supplements included. The significance of the collection needs explaining.

Charles Southwell (1814-1860) was born in poverty in London, the youngest of no fewer than 33 children. He became a bookseller in London in 1830 and became one of Robert Owen’s socialist missionaries, proving to be a proficient lecturer, although later he was to fall out with Owen. At about the same time he opened a freethought bookshop in Bristol and, in partnership with a local printer, William Chilton, published the first issue of the Oracle. The strapline gave a foretaste of what to expect: ‘FAITH’S EMPIRE IS THE WORLD; ITS MONARCH, GOD; ITS MINISTERS, THE PRIESTS; ITS SLAVES, THE PEOPLE.’

At first, the journal was relatively moderate in tone, but news soon reached Southwell that the authorities were displeased, and this seemed to have provoked him into raising the temperature. The fourth issue, dated 27 November 1841, begins with an article entitled ‘The “Jew Book.”’ which opens thus:

That revoltingly odious Jew production, called BIBLE, has been for ages the idol of all sorts of blockheads, the glory of knaves, and the disgust of wise men. It is a history of lust, sodomies, wholesale slaughtering, and horrible depravity; that the vilest parts of all other histories, collected into one monstrous book, could scarcely parallel!

At first such tactics met with success, with the Oracle achieving a circulation of around 4,000. Not since the early days of Richard Carlile’s Republican had there been anything like it. ‘The “Jew Book.”’ provoked a furious reaction amongst the pious, although it was not its troubling and overtly anti-Semitic nature that bothered them; rather, they were offended by its outspoken attack on Christianity. But it caused divisions in freethought ranks too. Despite his own earlier outspokenness, Carlile hated it, as did Julian Harney, and while such anti-Semitic sentiments did not provoke the outcry they would today, they sat uneasily with Robert Owen’s cultural relativism.1 It seems to me that parallels can be drawn between the divisions provoked by Carlile’s earlier pronouncements and G.W. Foote’s early Freethinker. Just how outspoken should you be about religion and the religious and how productive is being so outspoken likely to be?

Analysis of the journal’s contents suggests it had three related purposes. The first is already apparent; it was there to expose the absurdity, illogicality, and perceived immorality of Christian belief and heap visceral contempt upon it. The second was to expose the extent to which the Church was there to enhance and protect the interests of a privileged minority at the expense of what might loosely be termed the working class. Third, it promoted modern scientific theories in opposition to Christianity. Hence Southwell’s freethought was much more than a general distaste for religion—he regarded religion as a barrier to scientific and human progress.

Southwell used the journal to publish a series outlining his ‘Theory of Regular Gradation’, which followed the French geologist Pierre Boitard’s evolutionary thinking; accompanying illustrations from Boitard’s publications were also included, e.g. the ‘Fossil Man’, complete with monkey face. It was Chilton, however, who was the principal author of this series, taking over from Southwell and introducing a wider range of sources.

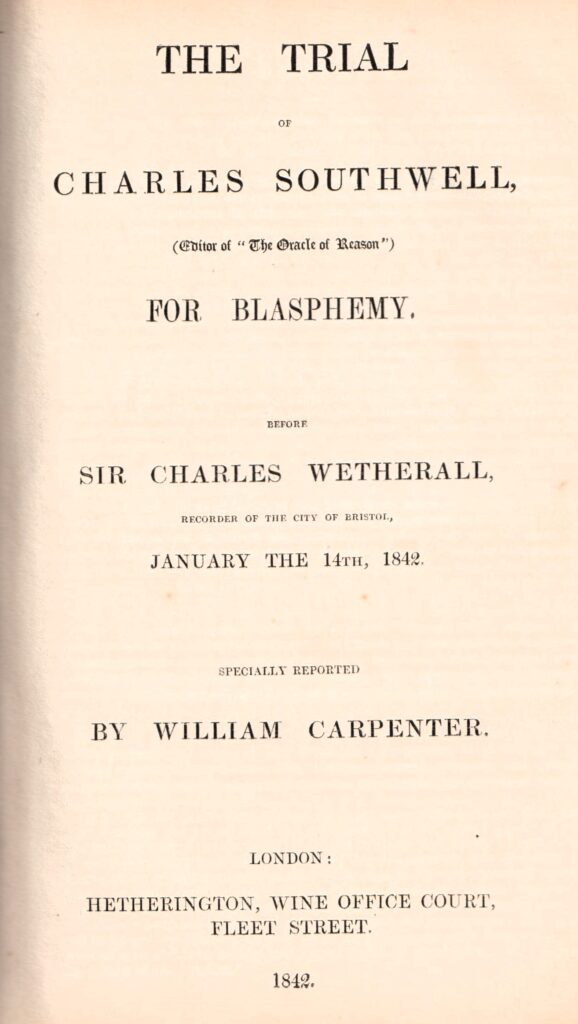

Southwell was arrested on a charge of blasphemy on 27 November 1841 and brought to trial on 14 January the next year. He defended himself and talked for several hours. His central argument was that he could not be guilty of a crime because what he had written was true, although this clearly failed to impress the jury who decided on a verdict of ‘guilty’ after deliberating for just ten minutes. He was sentenced to twelve months’ imprisonment and fined £100.

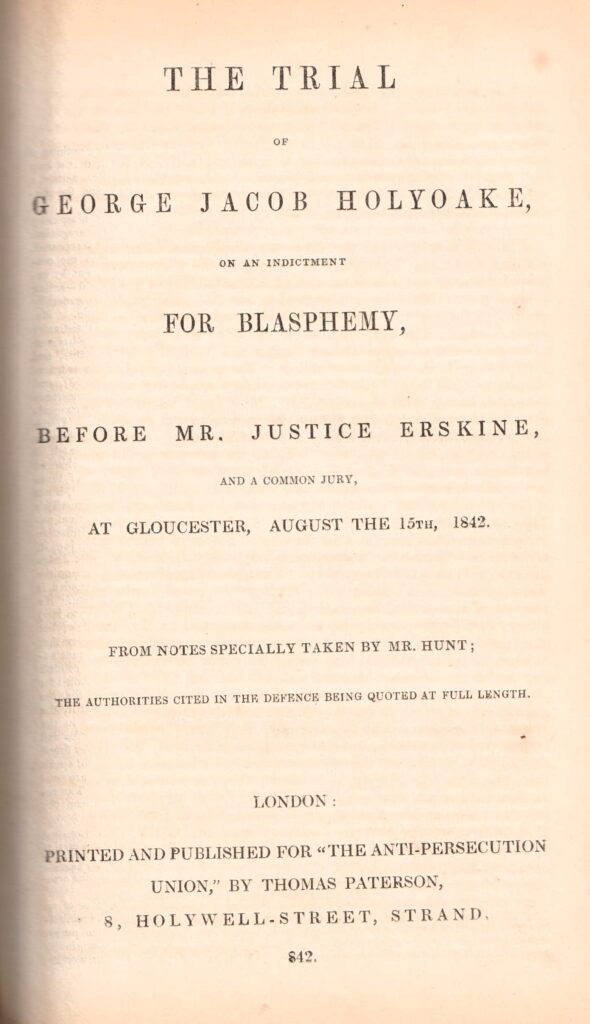

In 1842, the editorship passed to George Jacob Holyoake, who was to remain an important figure in the freethought movement into the next century. His approach was more moderate, but he in turn soon fell foul of the authorities when, after a lecture he had given in Cheltenham, he answered a question by expressing his disbelief in God and declaring, ‘If I could have my way I would place the Deity on half-pay’; meaning that in view of the economic distress suffered by many, he would reduce the sums devoted to religion.

Holyoake was arrested for blasphemy, tried on 15 August 1842, and sentenced to six months’ imprisonment in Gloucester Gaol. As Royle points out in Victorian Infidels, Holyoake’s arrest and trial were amongst the greatest events of his life. His martyrdom confirmed him as the undisputed leader of radical freethought, a position he was to retain until the emergence of Charles Bradlaugh. He was to outlive the nineteenth century and became central to a wide variety of progressive campaigns including cooperation and the demand for an extension of the franchise as well as freethought and secularism. His writings for a variety of journals, some of which he edited, provide an invaluable record of the period’s radical movements.

Thomas Paterson, who J.M. Wheeler described as a ‘man of coarser stamp’2, took over the editorship from 3 September 1842. Paterson shared the fate of his predecessors, being tried for blasphemy for exhibiting profane placards. Like Holyoake, he was not prosecuted for the content of the Oracle but rather for other activities (although these activities grew out of their editorships, which had promoted them both as dangerous dissidents). Paterson’s defence was never likely to elicit a jury’s sympathy; rather than trying to demonstrate the charges were false, he endeavoured to show that the Bible and Christianity deserved to be brought into contempt and reviled. As such he was virtually admitting his guilt, although his actions were designed to draw attention to his cause, something that was recognised by the judge, who impounded his Bible to prevent his reading texts ‘damaging to religion.’

Paterson was sentenced to three months’ hard labour in Tothill Fields, Middlesex. His defiance undimmed, he travelled to Edinburgh following his release to support two freethinkers who had been arrested for selling blasphemous works and began selling such works himself. He found himself in custody again and was sentenced to 15 months’ imprisonment. Soon after his release this time, he travelled to America, where he disappeared from the record. William Chilton became the fourth and final editor of the Oracle, but was more cautious than his predecessors, escaping prosecution.

Southwell was released from prison in February 1843 but refused to resume the editorship of the Oracle. According to Royle, this was

partly because he did not want to be made responsible for the debt it had accumulated under the management of Paterson, but mainly because he had changed his mind about the value of the tone which he had originally given to the paper and which Paterson had maintained.

By now the journal was in decline. Sales were insufficient to cover costs, and the second volume was only made possible by a donation of £40 from a relatively wealthy middle-class supporter, W.J. Birch. Circulation was hampered because unstamped papers could not be sent through the post free of charge and respectable local sellers and agents would not handle the Oracle. The final edition appeared in November 1843.

Both Southwell and Holyoake went their own, more moderate ways. Holyoake founded his own journal, The Movement, to which Chilton contributed and which survived until 1845, to be succeeded by The Reasoner. For his part, Southwell founded the short-lived Investigator before emigrating to Australia and then New Zealand. He died in 1860 and is buried in Auckland.

The Oracle and its founder, Charles Southwell, deserve their place of honour in freethought history. They, along with others, helped demonstrate the contradictions between science and Christianity and, however briefly, became the focal point around which a movement and philosophy began to crystallise and develop, a movement for which some remarkably courageous individuals were to sacrifice their liberty. When I hold my bound volume of the Oracle, I know I have in my hands something much more than just a bundle of paper.

- For freethinkers’ reactions to Southwell’s words, see Adrian Desmond’s recent book Reign of the Beast, which was, incidentally, recently reviewed by Michael Laccohee Bush in these pages. ↩︎

- This verdict was rendered in the first instalment of Wheeler’s ‘Sixty Years of Freethought’ series in the Freethinker, which was published throughout June and July 1897. ↩︎

Related reading

Charles Bradlaugh and George Jacob Holyoake: their contrasting reputations as Secularists and Radicals, by Edward Royle

Secularism and the limits of progress? By Nathan Alexander

Freethought and secularism, by Bob Forder

Morality without religion: the story of humanism, by Madeleine Goodall

How three media revolutions transformed the history of atheism, by Nathan Alexander

Freethought and birth control: the untold story of a Victorian book depot, by Bob Froder

Britain’s blasphemy heritage, by David Nash

From the archive: ‘A House Divided’, by Nigel Sinnott

The rhythm of Tom Paine’s bones, by Eoin Carter

The Freethinker Christmas Specials (Or, Happy Solstice!), by Bob Forder

From the archive: imprisoned for blasphemy, by Emma Park

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate