Although increasing knowledge over the last few centuries would appear to have disproved the claims of all religions beyond any reasonable doubt, changes in levels of public belief have been slow to catch up. Can an overview of the past give us any guide to a probable future and what we might do to help?

Until around 1500, Christianity, in Europe, held a powerful grip on people’s minds and any dissent was harshly suppressed. Large numbers had been executed by being burnt to death. But in the 1600s science began, in a very small way, to challenge religion. The story of Galileo’s difficulties in putting forward the evidence that the Earth orbits the Sun is well known.

By 1800 in Britain, however, the absolute truth of Christianity remained universally believed. Scientists, many of whom were ordained clergymen, were at pains to show that their researches did not threaten religious belief. God was said to have written two books, the Book of Scripture and the Book of Nature. It was confidently assumed that one could only confirm the other. This was believed despite the fact that a spherical, rather than flat, earth and heliocentrism, both contradicting the Bible, were by then fully accepted.

Further stresses began to arise when, in 1811, bones of an ichthyosaur emerged from the eroding cliffs at Lyme Regis in England. How could God’s creation become extinct? It was blasphemous yet undeniable. Genesis tells us that the land was created before the animals. So how did the ichthyosaur come to be 100 feet below the surface? Geologists found further ‘antediluvian monsters’ over the next few years. In the 1830s, in his Principles of Geology, Charles Lyell showed evidence that geological change had taken many millions of years. This contradicted the accepted date of creation of 23 October 4004 BC which had been calculated from scripture by Archbishop Ussher.

Some refused to accept the new evidence, but many were satisfied by the idea of ‘interpretation’ of scripture. For example, if we can say that some of the days in the creation story were millions of years long, then Genesis might still be true. Most people in the population were either unaware of these problems or were uninterested in them. On Sundays, they put on their best, went to church, and listened respectfully to the sermon—which would not, of course, contain any controversial ideas.

It was becoming harder to be sure that Christianity was right and that [other religions] were the superstitions of misguided savages.

As the nineteenth century went on, evidence mounted. Darwin hesitated for decades before publishing his ideas about evolution. He had good reason to do so. In the early part of the century, people had been jailed for publishing evidence against religion. By mid-century, this was less common, but blasphemy was still regarded with horror and could be fatal to anyone’s reputation.

Darwin’s Origin of Species was published in 1859 and was followed in 1871 by The Descent of Man. These blew a huge hole in religious claims, denying the divine creation of humanity. ‘Interpretation’ became a lot more difficult. Man being created by God in one day is difficult to reconcile with man being evolved from earlier animals by a process of natural selection over billions of years.

Around the same time, various German scholars had pioneered the ‘higher criticism’ of scripture, looking carefully at early documents in Hebrew and Greek. They showed that the Bible was full of contradictions, copying errors, forgeries, and stories that could be proved false by other known historical truths. These ideas began to penetrate the English-speaking world.

Meanwhile, the British Empire continued to expand and, in general, there was more travel—and thus more contact with other religions. It was becoming harder to be sure that Christianity was right and that the others were the superstitions of misguided savages.

One might have thought that, after all this, people would have just given religion up. There was now overwhelming evidence of its falsity. But nothing of the kind happened. The clergy carried on plying their trade, and other than a minority of individuals, people paid no attention to the new evidence, or, when they heard about it, they just lived with the unresolved contradiction.

For example, Jessica’s First Prayer was published in book form in 1867 and sold at least one and a half million copies by the end of the century; far more than any other book of the time (and certainly far more than the Origin). It was a sickly story about an orphan finding a good life by discovering Jesus. But its enthusiastic reception tells us how little the new discoveries penetrated the popular view about the ancient certainties of religion.

In 1883, G.W. Foote, founder of the Freethinker, was jailed for blasphemy. But by the turn of the century, it was easier to publish atheist material without being prosecuted. In May 1899 the Rationalist Press Association (RPA) was formed and produced atheist literature. They managed to sell books, but it was a niche activity. Most bookshops declined to sell them and some agreed, but only on an ‘under the counter’ basis. The RPA, together with various ‘ethical societies’, were forerunners of (or kindred with) today’s Humanists UK and the National Secular Society.

From 1900 onward the history is much more difficult to understand. Until perhaps 1950 there was little change. Atheists faced little persecution, although blasphemy remained a crime. But the influence of activists was minuscule. To promote atheism was something like promoting pornography; if not actually illegal, it was regarded as scandalous by the majority. The churches had no need to fear advocates of atheism; they were truly an inconsequentially tiny minority.

Religion tends to thrive in times of stress as people clutch at supernatural straws.

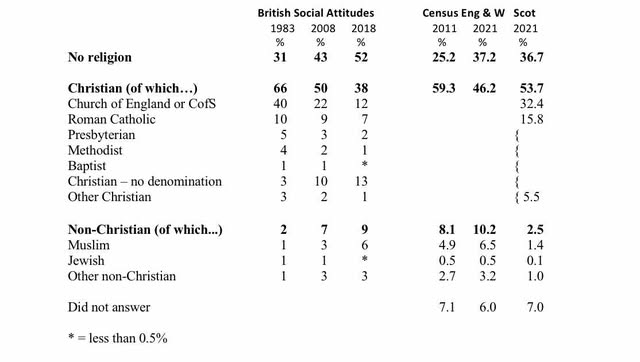

But in recent years in Britain, the influence of religion has, over a few decades, receded dramatically. In censuses and surveys, the number of people stating that they have no religion has grown and the proportion describing themselves as Christian has declined. Christianity is now followed by less than 50% of the population. (See Appendix.) Richard Dawkins’s The God Delusion (2006) has sold over three million copies worldwide. On the other hand, there has been a growth in minority religions due to immigration.

In general discourse, religion has disappeared from our vocabulary. Anyone in Britain who raises the subject of religion outside an occasion convened for that purpose is thought a bit of a crank. The saying of grace at formal dinners has mostly disappeared. References to scripture in scientific papers, common in the nineteenth century, have long since vanished. Humanist funerals are common. We often hear people saying, ‘I am not religious’, still wary of using the term ‘atheist’.

The question must be, why has this happened? It is surprising that it has not yet been carefully investigated. Although it is welcomed by non-religious organisations (e.g. Humanists UK, the National Secular Society, and Atheism UK) it is almost certainly not due to their activism, or not much of it is. Many of these organisations have stepped back from explicitly promoting atheism, which had really got nowhere, and have emphasised equal treatment for the religious and non-religious—a much easier place to find general agreement.

It is difficult to be certain why religion has declined, but easy to make untested hypotheses. Religion tends to thrive in times of stress as people clutch at supernatural straws. This might explain its survival in the war-torn first half of the twentieth century and its decline during the succeeding period of increasing prosperity and peace. Perhaps this prosperity has offered competing ways of spending one’s time; the garden centre is more interesting than church on a Sunday morning. Some have lost faith because of the sexual misdemeanours of priests, although that is not a logical reason to think religion false.

In an ideal world, children would be invited to think critically about the many facts which demonstrate the falsity of religion. Sadly, a lot of religious indoctrination remains, but children have begun to be taught about the different religions of the world. This has been done not to promote atheism but to encourage understanding between different groups. Nonetheless, children are likely more aware these days that they could not all be true.

And lastly, there is the least likely hypothesis of all. Perhaps a large number of people have begun to look at the discoveries of science and scholarship that have proven religion false.

So, in rough terms, we have seen a century of atheist activism from minority organisations, which was almost totally ineffective. This has been followed by almost a century without promotion of atheism during which religion seems to have withered of its own accord. Membership of freethinking organisations remains tiny despite the large segment of the population who identify as having ‘no religion’.

The situation in Britain is similar to that in many Western democracies. Even the United States, although trailing behind, has been moving in the same direction with the growth of the ‘nones’. But in some parts of the world, and even in the West, Islam and Hinduism are becoming more assertive. In Russia, the state promotion of atheism has been completely reversed.

So where should non-religious organisations in the UK go from here? If we are happy to see the decline of religion, one might suppose that it would be good to play a part in helping that along. But, without a clear understanding of what is going on, it is difficult to know how. Still, perhaps some attempts should be made, monitoring results to get an idea of what works best.

Here are some suggestions:

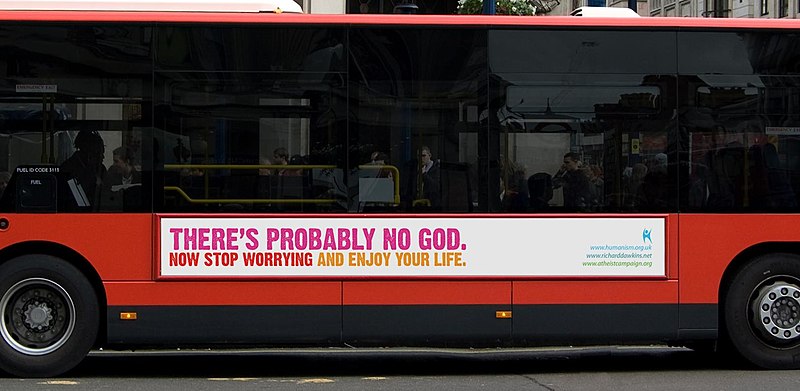

1) It is the right policy to avoid open confrontation. Apart from unpleasantness, it would also be unproductive and might threaten the equality claims vis-à-vis religious privilege that have been successful. But there may be room for occasional exceptions. Condemnation from, as it were, the pulpit can be a great source of publicity and recruitment. The atheist bus campaign of 2008-2009 was successful, but such things must be used sparingly.

2) A full understanding of the evidence and arguments for and against atheism is a big and interesting subject. Most people who leave religion do not have a deep understanding of it. It would be useful to offer instruction, but only to those who are self-selected. This would build a more solid base without confrontation.

3) The big problem is the indoctrination of schoolchildren, which continues without much change. It is difficult to see how this can be opposed without confrontation. Perhaps it is best to stress equality and balance, which certainly are not taught today. To have a good religious education, even believers should be aware of the questions that have arisen because of science and scriptural scholarship. These should not be brushed under the carpet as they are now.

Appendix: UK Statistics

In the UK, surveys have shown a steady decline in religious belief and observance. Here are some results for the levels of religious identity from 1983 to 2021. There has been a recurring difference between the British Social Attitudes Survey (BSAS) and the Census results. This could be due to the form of the questions or the circumstances in which they are answered. In addition, there may be a risk of answers being determined by a sense of community rather than actual belief, and there has also been a reluctance of non-believers to declare their opinion (but this has decreased over recent decades). Such effects make the results imprecise but there are clear trends.

Note: The Census question is ‘What is your religion?’ whereas the BSAS question is in two steps. First, ‘Do you consider yourself as belonging to a particular religion?’, and then, ‘If “yes”, which one?’ This may explain the difference in results. The Census may cause some people to put down a religion which is only nominal, whereas the BSAS may pull some who are non-denominational believers into the ‘no religion’ category. But the trend is notably the same in both.

Similar figures are found throughout most of the democratic Western nations. Even the United States, which had seemed an outlier, is showing a decline in religious observance. Sadly, in some other parts of the world, there have been signs of increasing religiosity accompanied by aggressive enforcement.

Related reading

Book’s From Bob’s Library series, by Bob Forder

Charles Bradlaugh and George Jacob Holyoake: their contrasting reputations as Secularists and Radicals, by Edward Royle

Secularism and the limits of progress? By Nathan Alexander

Freethought and secularism, by Bob Forder

Morality without religion: the story of humanism, by Madeleine Goodall

How three media revolutions transformed the history of atheism, by Nathan Alexander

Freethought and birth control: the untold story of a Victorian book depot, by Bob Froder

Britain’s blasphemy heritage, by David Nash

From the archive: ‘A House Divided’, by Nigel Sinnott

The Freethinker Christmas Specials (Or, Happy Solstice!), by Bob Forder

From the archive: imprisoned for blasphemy, by Emma Park

‘Enthralling and useful’: Adrian Desmond’s ‘Reign of the Beast’, reviewed, by Michael Laccohee Bush

What I believe: Interview with Andrew Copson, by Emma Park

Bringing back the dialectic: interview with Stephen ‘Rationality Rules’ Woodford, by Samuel McKee

The new faces of unbelief for Generation Z: the rise of the British social media atheists, by Samuel McKee

‘Religion is a killer now’: interview with Professor Peter Atkins, by Samuel McKee

Storm over a tea-cup? The ‘Mug-Gate’ teacher speaks out, by Matt Lovell

There is such a thing as society: faith schools and the vacuum left by the state, by James Bloodworth

The case for secularism (or, the church’s new clothes), by Neil Barber

Three years on, the lessons of Batley are yet to be learned, by Jack Rivington

Faith schools: where do the political parties stand? By Stephen Evans

Religion and belief in schools: lessons to be learnt, by Russell Sandberg

Atheism, secularism, humanism, by A.C. Grayling

A reading list against the ‘New Theism’ (and an offer to debate), by Daniel James Sharp

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate