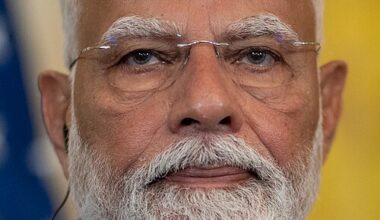

As readers of the Freethinker are likely aware, MP Tahir Ali recently advocated in Parliament for legislation prohibiting ‘the desecration of religious texts and the prophets of the Abrahamic religions.’ Although his call was made during Islamophobia Awareness Month and in a context of higher rates of anti-Muslim hate than at any other point in recent history, the MP for Birmingham Hall Green and Moseley’s call for legal protection of specifically religious symbols and values has resulted in concerns about potential implications for free speech and the proper role of the state in regulating expressions of religious dissent and religious dissidence. Though Humanists UK has attained assurances from the government that there are no plans to reintroduce blasphemy laws or restrict free expression around religion, this episode—not to mention the current Prime Minister’s characteristically lacklustre response to Ali in Parliament—raises a question: how are we to combat the aggressive rise of anti-Muslim hate, egregious examples of which were abundantly displayed during this August’s riots, without compromising upon secularist commitments to the defence of freedom of conscience and expression?

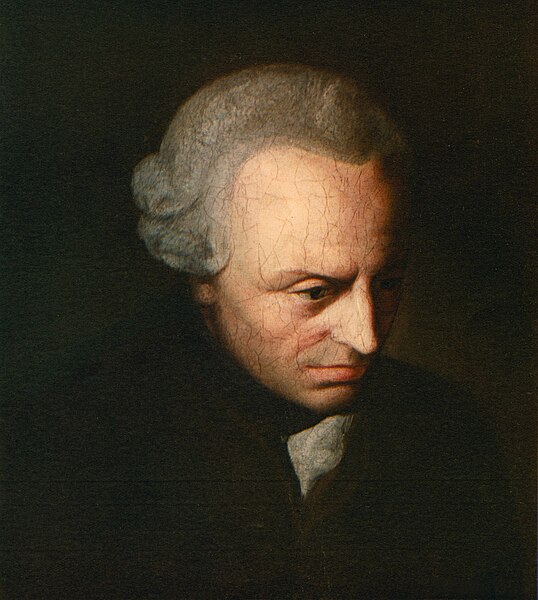

Many among this publication’s readership may also be aware that this year marked 300 years since the birth in Königsberg (now Kaliningrad) of Immanuel Kant—one of the greatest and most influential philosophers in history. Anniversaries such as these are apt to prompt reflection upon the legacy of a pioneering thinker and comparisons between their times and our own. They invite us to ask whether we still have anything to learn from so historically distant a figure as Kant. A leading champion of the Aufklärung—Germany’s contribution to the Age of Enlightenment—Kant took pride in the spirit of free inquiry which he saw as the defining trait of his historical period, arguing for academic freedom and against censorship of the press.

‘Ours is the age of criticism, to which everything must submit’, he wrote in The Critique of Pure Reason, meaning by ‘criticism’ not the vitriolic name-calling and unsubstantiated accusations characteristic of certain billionaire-owned social media platforms and associated political opportunists, but the patient and disciplined process of understanding through rational scrutiny. From this sustained project of questioning, challenging, and evaluating, Kant maintains, nothing is exempt—not even the doctrines of a religion or the legislation of a state.

To return to certain legislative proposals recently mooted in Parliament, and although etymology is an unsure guide to the current meaning or use of a word, it is perhaps worthy of note that the origins of the term ‘desecration’ lie with the act of divesting something of an allegedly sacred status, and hence of removing that thing from an elevated position which commands respect or even reverence. With this in mind, accusations of desecration are premised upon the assumption that whatever is alleged to have been ‘desecrated’ is unlike ordinary things—which is to say that it is in a class apart, meriting special treatment and attitudes of veneration. If that is the case, however, then refusal to consent to the allegedly privileged status of that thing, and to regulate one’s actions, attitudes, and expressions accordingly, is to be as guilty of desecration as if one scuffed a Quran.

As such, legislation against desecration may be expected to raise concerns amongst those of us who believe that it is for the individual conscience to decide what should be valued in this privileged manner, rather than for the state and its legislative and juridical representatives, or, indeed, the followers and advocates of one or another set of religious doctrines, values, and practices. For the state to enforce respect for the purportedly ‘sacred’ status of certain symbols and institutions, religious or otherwise—although the harsh policing of republican protests at last year’s coronation suggests that caution is advised in offering the monarchy as an example here—seems, at the very least, to mark a worrying departure from the ideal of open-minded critical inquiry in which Kant invites us to participate.

Though justly confident of having secured his place in philosophical history, Kant lived in a manner which gave evidently little consideration to his later biographers—of whom there have been understandably few given his life of near tragi-comic uneventfulness. Never in his life did he set foot more than 30 miles from his hometown, and it is said that fellow Königsbergers would set their clocks by the regularity of his walks—a daily occurrence from which only news of the outbreak of the French Revolution ever once led him to depart.

During a life otherwise exasperatingly unmarked by dramatic incident, however, one episode merits attention. In October 1794, Kant received a royal correspondence from the state censor expressing extreme displeasure at certain writings in which he was alleged to have ‘misused’ his philosophy ‘to distort and negatively evaluate many of the cardinal and basic teachings of the Holy Scripture and of Christianity’. In order to avoid His Majesty’s ‘highest disfavour’, Kant had to ‘give at once a most conscientious account’ of himself. Failure to mend his ways, he was told, must be expected to result in ‘unpleasant measures’ for his ‘continued obstinacy.’

The prompt for this act of state intervention was the recent publication of Kant’s Religion within the Boundaries of Mere Reason, an effort to assess which kinds of religious doctrine and organization might meet with our unprejudiced rational approval. Kant had already experienced obstacles from the state censor in publishing parts of this work and told friends that he expected it to result in the loss of his position at the University of Königsberg. Whatever today’s audiences might make of his attempts to give a secular interpretation and defence of such dogmas as original sin and divine grace, and whatever Kant’s true views about the validity of religion and the existence of God, many of Kant’s contemporaries (the King of Prussia included) were struck by the temerity of his refusal to excuse received scriptural wisdom or ecclesiastical authority from the same critical standards he had employed elsewhere in his studies.

Especially concerning for Kant’s more orthodox religious critics was his insistence that the doctrines and practices of any religion should answer to a secular morality of human dignity and freedom which affords no role to divine commandments. So uncompromising was Kant, in fact, in his suspicions of familiar arguments for divinely sanctioned ethics (and, indeed, for the very existence of God) that he earned the enviable title of der Allzermalmende (the All-Destroyer). Contemporary freethinkers and darkwave musicians will undoubtedly be disappointed to learn that this title is already taken.

Kant must have given either a persuasive or a carefully worded account of himself (or both) in his reply to His Majesty’s demand. While he had prepared himself for immediate dismissal, Kant ultimately kept his position—whereas Wöllner, the author of the royal correspondence in question, came satisfyingly close to losing his own. The apparent audacity of Kant’s dealings with state and religious establishments might also remind us that he coined for his age of criticism and enlightenment the motto Sapere aude (dare to know). Enlightenment, Kant tells us, is the liberation of humankind from its ‘self-imposed immaturity.’ The German term Unmündigkeit, which standardly gets translated here as ‘immaturity’, can also mean ‘tutelage’ or ‘minority’ and implies a sheepish deference to authority. Since Mund means ‘mouth’, one who is unmündig is somehow presumed unqualified to speak on their own behalf. According to Kant, however, it is precisely in our capacity to reach our own conclusions and come to a free and rational decision about which values to uphold and how to direct our lives that our dignity as human beings consists.

Between the alleged dignity of a religious text or symbol, then, and that of the human conscience, there is simply no contest according to Kant. To demand respect for the former is thereby to deny it to the latter. At the same time, however, it is an impermissible affront to the dignity of a person to target them and deny their humanity simply for exercising their inalienable right to decide upon their religious values or rejection thereof.

Opponents of recent proposals for anti-desecration legislation may therefore find an ally in Kant. Prejudice against religious minorities should be addressed not by insulating texts and symbols from criticism but by championing the humanity and dignity of every citizen, irrespective of their religious affiliation or lack thereof. Respect for our common humanity entails, however, that it is left to each of us to decide what, if anything, we are to treat as sacred, without the threat of reprisal either from the state or from misinformation-fuelled stooges of one or another reactionary and dehumanising agenda.

The featured image for this article (at the top) is a photo of Salwan Momika burning a Quran in 2023. Photo credit: Frankie Fouganthin. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Related reading

The power of outrage, by Tehreem Azeem

The Satanic Verses; free speech in the Freethinker, by Emma Park

Secularism and the struggle for free speech, by Stephen Evans

Free speech in Britain: a losing battle? by Porcus Sapiens

‘F*** it, think freely!’ Interview with Brian Cox, by Daniel James Sharp

On trial for blasphemy: the Freethinker’s first editor and offensive cartoons, by Bob Forder

Is all publicity good publicity? How the first editor of the Freethinker attracted the public’s attention, by Clare Stainthorp

‘The best way to combat bad speech is with good speech’ – interview with Maryam Namazie, by Emma Park

Image of the week: first edition of ‘The Satanic Verses’, by Daniel James Sharp

Blasphemy and violence: review of ‘Demystifying the Sacred’, by Adam Wakeling

Three years on, the lessons of Batley are yet to be learned, by Jack Rivington

The Enlightenment and the making of modernity, by Piers Benn

Cancel culture and religious intolerance: ‘Falsely Accused of Islamophobia’, by Steven Greer, by Daniel James Sharp

Blasphemy and bishops: how secularists are navigating the culture wars, by Emma Park

Britain’s blasphemy heritage, by David Nash

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate