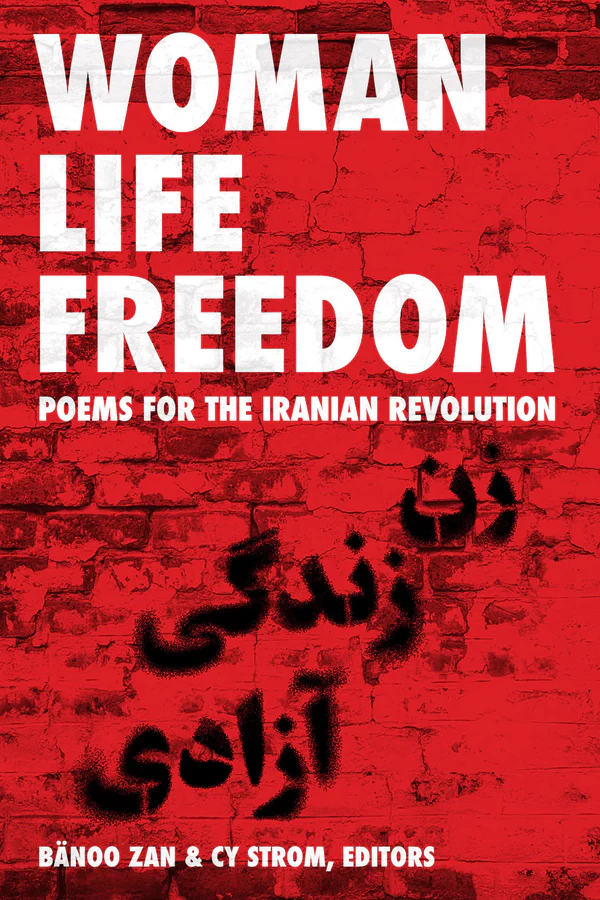

Are poets really ‘the unacknowledged legislators of the world’, as Percy Bysshe Shelley put it in 1821? This is a question on which the jury has been deliberating since long before there were any such things as modern juries. And this is the question explicitly posed in a new collection of poems edited by Iranian-born Canadian poet Bänoo Zan and freelance editor Cy Strom, Woman Life Freedom: Poems for the Iranian Revolution.

This collection gathers a range of poets—Iranians and non-Iranians, exiles and emigrants, the certain and the uncertain—who share a single purpose: to declare and embody solidarity with the people, especially the women, of Iran, whose decades-long struggle against theocracy was revivified and intensified by the murder of Mahsa Jina Amini in 2022 for wearing ‘improper’ hijab. Even if these poets are not on the ground in Iran, ‘doing the necessary work’ in Strom’s introductory words, they can bear witness. The struggle is a universal and human one, in other words: ‘No one population or culture is the only victim of the oppressor, the only body engaged in the struggle.’ The revolutionary ferment which followed Amini’s death was nigh-unprecedented in Iran, or indeed in any other country, though one might stop short of declaring it, as Strom does, ‘the first ever feminist revolution’.

(For one thing, as Maryam Namazie has written, the famous ‘Woman Life Freedom’ slogan was ‘first raised in Rojava in Syrian Kurdistan, a centre of secularism in the middle of a war zone.’ In fairness, and as Namazie also notes, it was the ongoing Iranian struggle which globalised this slogan. As an aside, Mahsa Jina Amini was a Kurd, and the Kurdish people, Kurdish women in particular, have long been one of the world’s most progressive, revolutionary forces, standing up to fascism and imperialism for many a long year. One need not deny the imperfections of and blemishes upon the Kurdish struggle to recognise this fact. Nobody is entirely consistent, but the Kurds have come closer than most. And who could fail to stir at the sight of Kurdish women fighting on the frontlines against the theocratic, fascist scum of Islamic State and the like? They carry on the noblest of traditions. How appropriate, then, that the secular, democratic, feminist revolution in Iran has its origins in Kurdish resistance. And it is almost too perfect that Amini’s Kurdish name, Jina, means ‘life’; in the original Kurdish, ‘Woman Life Freedom’ is Jin Jian Azadi.)

Perhaps only the Taliban regime of Afghanistan is more anti-life than the mullahs of Tehran. Just think of it: an ordering of society so disgusted by music, booze, homosexuality, free thought, and—not to mention—strands of female hair that it has to beat and rape and murder those who dare to challenge it by tolerating, or even embracing, such things. As Afsar Marefat puts it in one of this book’s poems, ‘Even the pavement weeps’ (translated by Ari Honarvar):

The old demons

have declared war on beauty and joy

They’re bloodthirsty for jasmine and rose buds

Their enemy: love, music, and laughter.

The Islamic Republic has been around for a long time, but its brittleness is shown in the fact that free-flowing hair terrifies it into acts of such brutal repression as we have witnessed for the past two and a half years or so. Some lines from several of the poems in Woman Life Freedom make the point better than I ever could:

music enslaved by councils of codgers engraving edicts on female flesh

~ Giovanna Riccio, ‘You Know Me’

The kings create fabrications, they weave society as a scarf that strangles its princess.

But. She plucks, plucks, plucks away with every breath of her being.

…

One word, and one strand at a time. A girl in pigtails uttered words that shredded the hair from the kings.

And the world heard the echoes of “Woman, Life, Freedom”.

~ Rasha Barrage, ‘She reads a fairy tale’

Speak it boldly, let it resound

with such force that the stagnant

air is stirred, compelling veils to fall away,

and women’s locks to cascade freely,

draping over their shoulders as they unite

in town squares, dancing around

bonfires, igniting the flames of liberty

by burning their hijabs.

~ Nilofar Shidmehr, ‘Say Her Name: Mahsa Jina Amini’

Unveil your rage, my

sister, unveil the night.

Let the old cloaked men

who declare heaven is

beneath your feet, while they

put you in a dark well, see

your might.

Unveil your rage, my

sister, unveil the night.

Set this forsaken land

alight, with a bonfire of veils

from the Caspian to the

Gulf.

Blaze away this blight.

~ Ala Khaki, ‘Veil Not’

This collection inhabits and champions the great and ancient culture of Iranian—or should that be Persian?—poetry. It also avowedly invokes, as well as evokes, the tradition of revolutionary song-making—and in the internationalist style at that. As Strom notes in his introduction, Italian and Chilean radical music was adapted by the protestors in the wake of Amini’s murder (the Second World War Italian anti-fascist song ‘Bella Ciao’ was particularly popular). Here, I can’t help but mention that all this put me in mind of the revolutionary poetry of Pablo Neruda1 and the beautiful scene from the Star Wars series Andor in which the galaxy’s oppressed rise up against the Empire after making music and being inspired by a dead woman’s call to rebellion. (Internationalism is what multiculturalism should always have been, and truly is.)

Strom notes the influence of the early twentieth-century revolutionary Iranian poet Aref Qazvini, but I like to think that the real ancestor of today’s singing revolutionaries is Omar Khayyam, who, around a thousand years ago, lyricised the joys of wine and sex against the Islamic authorities in his own day, or what he called ‘The wintry soul that hates to hear a song,/The close-shut fist, the mean and measuring eye,/And all the little poisoned ways of wrong.’ (Richard Le Gallienne translation.) Echoed, perhaps, by Mahdi Ganjavi in ‘For the sake of “for” itself’:

For state-sanctioned conflicts in the name of love,

For your authority in defining the limits of the body,

For our vulnerable, homeless, and manipulated dignity,

For attempting to forget the relentless barrage of nonsense,

For the ideological webs spun around every fragment of poetry,

To safeguard Rumi, Hafez and Sa’di from coercion’s grasp,

For incessantly breathing in religious smog…

(Alas, that Khayyam is omitted in the penultimate line here.)

Now that I have started making these connections, indulge me a little longer. In her afterword to Woman Life Freedom, Bänoo Zan argues that ‘The job of a writer is to critique traditions, institutions, cultures, religions, customs, or nations. Epic and panegyric are passé. Our job is to write exposés.’2 Perhaps this is the only way in which writers can be legislators, acknowledged or not. Now, compare Baal the poet, a character who falls afoul of the prophet Mahound in Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses (1988): ‘A poet’s work is to name the unnameable, to point at frauds, to take sides, start arguments, shape the world and stop it from going to sleep.’

Rushdie, of course, is another of the Islamic Republic’s many victims. Literature, clearly, is the enemy of theocracy. But he, too, has triumphed, surviving exiles and assassination attempts to continue producing beautiful and humane works of fiction and non-fiction. ‘Words are the only victors’, as he has written in his feminist, secularist, humanist novel Victory City (2023). (Would it be too much to make a connection between Rushdie’s loss of an eye to a fanatic in 2022 and a poem by Donna Langevin in this collection about women blinded by the Iranian regime who ‘wept tears of blood’?) Ovid outlives the empire that banished him, and Federico García Lorca outlives the Spanish fascists who murdered him. Poetry, in both the narrow and broad senses, lives on. More, it shines on. So it has been with Khayyam and Qazvini, and so it will be with the poets whose lines are printed in Woman Life Freedom, the most recent addition to the great canon of the Iranian literature of resistance.

‘[We] shall build a new citadel’, as Ala Khaki writes. The future of Iran is somehow both uncertain and assured. Uncertain because there will be repressions and reversals, and change might take a long time and come in an unwelcome form. Assured because the regime cannot indefinitely survive this new, most broad and intense and radical awakening of Iran’s women and men and youth to its tyranny. A misogynistic theocracy (though perhaps that is a tautology) cannot long rule such an intelligent and feminist and irreligious population as that of Iran. A feminist revolution? Yes. But more importantly, a deeply human one.

‘I am a woman. What words are they afraid of? My hair is an adverb of kindness. Bring me a light breeze and feet that walk freely. Freedom. A poem knows how to plant it like a seedling. Make it a verse of life.’ (Mansour Noorbakhsh, ‘Make It a Rhyme’.) Satanic verses, verses of life, verses that might just topple one of the world’s oldest and vilest theocracies.

Even amid the self-immolation of the world’s oldest and largest secular democracies (the United States of America and India, respectively), the people of Iran might just be ushering in a new one—and perhaps in doing so they will remind those in the so-called free world who are tired, lazy, and disaffected of the true meaning and value of liberty.

In short: Woman Life Freedom is an astonishing, riveting, galling, inspiring, infuriating, sickening, saddening, beautiful collection of poetry. For me, anyway, it is a testament of life against one of its great enemies: religion. I have only been able to quote a few of its poems in this review; it contains many more, a diversity of forms and registers and perspectives well worth paying attention to if you care even a little about what is happening in Iran—and the world.

- Alas, I have to ignore here the controversy surrounding Neruda’s confession of raping a woman in 1929. But, as Isabel Allende has argued, ‘Like many young feminists in Chile I am disgusted by some aspects of Neruda’s life and personality. However, we cannot dismiss his writing. Very few people – especially powerful or influential men – behave admirably. Unfortunately, Neruda was a flawed person, as we all are in one way or another, and Canto General is still a masterpiece.’ Demythologising great men (and women) need not mean denying their stature or influence, nor need it mean that we are now unable to take inspiration from them.

↩︎ - This afterword, entitled ‘Against the Tyranny of Home: A Call for (Self-)Critique’, is also a powerful rebuttal of relativism and parochialism:

It is easy to rant against outsiders, to blame them for our misery, to absolve ourselves of any responsibility.

It is easy to forget that the hell we escaped from was a hell, and that was why we left it behind. It is easy to forget that our own people were responsible for making our homeland so uninhabitable we had to leave.

…

In short, it is easy to write nostalgically about the idyllic fictional homelands. It is easy to self-stereotype, self-Orientalize, self-Occidentalize, self-pity.

…

As an immigrant, I am fed up with expectations that want me to be an apologist or propagandist for my religion, culture, or country.

This is echoed in the book’s method of selecting poems—via a blind submission process. As mentioned above, the poets are diverse in origin and perspective. And, in a blast for universalism, Zan goes on to say: ‘Reader: Whoever you are and wherever you come from, the enemy is your enemy—and the home is your home. Because all people are your own people.’

↩︎

Related reading

The ‘Women’s Revolution’: from two activists in Iran, by Rastine Mortad and Sadaf Sepiddasht

The Silent Revolution Against Religious Oppression in Iran, by Siavash Shahabi

The Racism of Anti-Racists: Bourdieu, Said, and Inverted Orientalism, by Siavash Shahabi

No Hijab Day, 1 February: Confronting Misogyny, by Maryam Namazie

‘Words are the only victors’ – Salman Rushdie’s ‘Victory City’, reviewed, by Daniel James Sharp

Rushdie’s victory, by Daniel James Sharp

Image of the week: celebrating the death of Ebrahim Raisi, the Butcher of Tehran, by Daniel James Sharp

The hijab is the wrong symbol to represent women, by Khadija Khan

Iran and the UN’s betrayal of human rights, by Khadija Khan

Rap versus theocracy: Toomaj Salehi and the fight for a free Iran, by Noel Yaxley

Afghan Tourism or Taliban Whitewashing? by Zara Kay

A Small Light: Acts of Resistance in Afghanistan, by Zwan Mahmod

Feminism and religion are incompatible, by Maryam Namazie

The Taliban’s unceasing war on Afghan women, by Khadija Khan

Secularism is a feminist issue, by Megan Manson

Faith Watch, March 2024, by Daniel James Sharp

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate