Astrophysicist Lawrence M. Krauss has been one of the staunchest defenders of science this century. Now, he has rallied powerful friends and allies to address the great academic challenge of our time: the incursion of anti-science, anti-truth ideology into academia and even the sciences themselves.

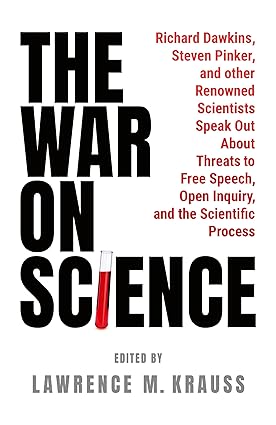

If you were seeking out expert opinion from those in the know about this very real problem, then the recent essay collection edited by Krauss, The War On Science, is the book for you. It delivers the views of well-known academics like the biologists Richard Dawkins and Jerry Coyne and the mathematician and physicist Alan Sokal, and it also contains contributions from people whose names you may not recognise, but who are leaders in their field from prominent institutions with first-hand experience of what is happening to science in the halls of academia. This book is an outstanding contribution to the question of what is going on, and I heartily recommend it.

As a scientist and academic myself, I have experienced my fair share of these issues. I have sat through lectures to hundreds of students where academics have boldly preached that science is a Western fiction rooted in imperialism and is no more valid than any other ‘way of knowing’. I have been to education conferences where rallying cries to political activism, rather than ideas about education, have been delivered. I have been at institutions where students have held rallies saying that if only Israel did not exist, climate change would not be a problem (seriously). It is easy to think these issues are exaggerated, but they are very real indeed.

One of the book’s epigraphs comes from former Harvard president Lawrence Summers: ‘Universities need to abandon the concept that they have a central role in Moral Education.’ Unfortunately, I have heard university administrators state that the primary purpose of the university is not education at all, but to shape the future of the world through activism. This is a peculiarly Marxist idea of the purpose of education and is the exact opposite of what education should be. This brand of philosophical thinking is particularly dangerous when it comes to the STEM subjects.

The book is broken down into five sections. The first deals with free speech issues, the second with ideological corruption in academia, the third addresses the impact of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) policies, the fourth is a brief detour into the gender ideology controversy, and the final section asks what can be done to remedy these issues.

Krauss sets the tone with a blistering opening in the form of a lucid and detailed introduction to the book. It is one of the best chapters in the collection and worth the price alone, especially for anyone in doubt about the reality of the madness which has captured our institutions. ‘It is vitally important, for the progress of scholarship and the scientific health of the nation and the world, for these trends to be opposed’, he argues. Krauss is an evangelist for merit, and you can sense the heartbreak in his words at the fierce opposition to merit in the academy in favour of Critical Social Justice (‘wokeism’) and DEI. Krauss states correctly that there is absolutely no evidence that our scientific institutions are inherently racist at their core and need to be deconstructed. He is aghast at the incredible amount of grant money that is earmarked for research being spent instead on DEI, antiracist training, and bogus, woke scholarship instead of on medicine, science, and technology.

Richard Dawkins then takes up the baton with some of his finest writing in years. His chapter, ‘Scientific Truth Stands Above Human Feelings and Politics’, is an outstanding call to reason, and he has receipts to back up every one of his hammer blows. Possible retorts that his pride in science strays into arrogance are refuted by his description of the humility at the heart of the scientific endeavour. One need only contrast this with the humanities and, in particular, the Critical Social Justice movement to see who is truly arrogant: ‘The human conceit here is the idea that personal feelings can change reality.’

Dawkins is one of several contributors who reference Soviet-era Lysenkoism as a model for the kind of failure we have seen before and now see rearing its ugly head once again. He walks us through the chilling story of the ideologically polluted ‘science’ that killed more people than either of the World Wars through its replacement of ‘bourgeois’, ‘capitalist’ biology with ‘communist agriculture’. For those who are unfamiliar with the Lysenko affair, Dawkins provides a brilliant introduction to this horrific warning tale.

Dawkins is also at his humorous best despite the heavy subject matter. When dealing with gender ideology, for example, he quips that, ‘If I ever encounter a doctor who gives me a full medical examination and then asks me what sex I am, I’d be inclined to ask for a more thorough examination, if not another doctor.’

Alan Sokal was one of the earliest academics to publicly identify the rot in some parts of the humanities (see his 1997 book, co-authored with Jean Bricmont, Fashionable Nonsense), so I am delighted that he has contributed a chapter. His voice is one that needs to be heard on this issue. Likewise, the marketing professor and champion of evolutionary psychology Gad Saad is another lucid writer who has much experience with the ideological corruption of the present era. The historian Niall Ferguson provides a wealth of historical context that serves as a forewarning for those in doubt about the nature and scale of the problem today.

Throughout each section and in each essay, there is no shortage of proof offered. The contributors rely not on hearsay or anecdote, but on published material and robust evidence. Sadly, many of the contributors have themselves fallen victim to Critical Social Justice-inspired cancel culture.

The section on the DEI issue was quite alarming to read. I really don’t think the general public has any idea of how huge this problem is, and the overwhelming majority would certainly not tolerate the concomitant undermining of science and medicine if they did. The brief section on gender ideology is very well written and a fine contribution to the discussion.

I was pleased that the final section did a good job of providing some reason for optimism, rather than leaving us alone in our gloom. This is not a doomsday book announcing the apocalypse, but rather a stern warning with hope for the future, as the tide may finally be beginning to turn. The election of Donald Trump last year brought a swift flurry of executive orders to address some immediate concerns in US institutions, and public opinion has turned against the ideological erosion of academia.

(Trump’s own attacks on universities deserve a book of their own, and it would be unfair to criticise The War on Science for not dealing with this problem, given the timing of publication. No doubt most of the contributors are as opposed to right-wing corruption of the academy as they are to woke subversion of it. Indeed, Krauss has written elsewhere and at length about ‘Trump’s war on science’.)

Yet one laments the loss of two academic generations to the madness and the fact that the institutions are still deeply entrenched with ideologues.

It is little surprise that Krauss and Dawkins no longer debate priests, bishops, and other religious apologists as much as they did in their New Atheist days. They have both made remarks to the effect that there are now different, perhaps even bigger, fish to fry. What has not changed is that they are still dealing with religious extremists, but arguably ones with far more power and far more hatred of science than anyone they dealt with twenty years ago. I am sure that each of them would pray, perhaps literally, for the days when they debated apologists and creationists rather than tangling with the newer and much more insidious beast that currently occupies them. In any event, The War on Science deserves its place alongside their and the other authors’ previous contributions advocating for science and reason against ideological madness, and I can only repeat my wholehearted recommendation of it.

Related reading

The future of biology, science vs. religion, and ‘ideological pollution’ in science: Interview with Jerry Coyne, by Samuel McKee

Rescuing our future scientists and engineers from quitting before they start, by Samuel McKee

80 years on from Schrödinger’s ‘What Is Life?’, philosophy of biology needs rescuing from radicals, by Samuel McKee

‘We are at a threshold right now’: Lawrence Krauss on science, atheism, religion, and the crisis of ‘wokeism’ in science, by Daniel James Sharp

British Islam and the crisis of ‘wokeism’ in universities: interview with Steven Greer, by Emma Park

My “lived experience” with the cult of “Social Justice”, by Rio Veradonir

My punk rock cancellation, by Gerfried Ambrosch

Defending liberalism: interview with Helen Pluckrose, by Daniel James Sharp

‘F*** it, think freely!’ Interview with Brian Cox, by Daniel James Sharp

On sex, gender and their consequences: interview with Louise Antony, by Emma Park

Can there be peace in the culture wars? Interview with A.C. Grayling, by Daniel James Sharp

‘A godless neo-religion’ – interview with Helen Joyce on the trans debate, by Emma Park

The falsehood at the heart of the trans movement, by Eliza Mondegreen

‘An animal is a description of ancient worlds’: interview with Richard Dawkins, by Emma Park

‘When the chips are down, the philosophers turn out to have been bluffing’, interview with Alex Byrne by Emma Park

1 comment

Excellent, I and my husband were there for this book launch, its was brilliant and I enjoyed reading the book with their voices in my head. Great review.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate