The Freethinker’s themes of ‘history’ and ‘civil liberties’ this September and October provide an opportunity to reflect upon the crime which has regularly tripped up atheists, agnostics, freethinkers and secularists – blasphemy.

It is relatively easy to trace the development of this offence in the nations of the UK and in Ireland. Although both Scotland and Ireland diverged from the experience of England, in later years the founding principle of the law in each of these countries was the same. Statutes were passed in England and Scotland, the latter witnessing the only execution specifically for blasphemy in mainland Britain in 1697. The statute law in England was barely used, and the principle of blasphemy prosecution was kept alive far longer than it might have otherwise been by the use of the English common law offence of blasphemous libel. When invoked in court, this was a law developed by judges, who had to interpret the content of blasphemy cases in their contemporary context, and to consider what level of religious debate and criticism appeared to be permissible within society at any given moment. Thus definitions altered and the law was made acceptable to each generation, sometimes even drawing praise from civil servants and others who saw it as an organic, evolving solution in a country that was slowly but surely becoming more progressive.

The history of these laws, or what Hypatia Bradlaugh-Bonner, daughter of Charles Bradlaugh, called ‘penalties upon opinion’, can be researched and followed through previous scholarship. But what needs recapturing and retelling to a wider audience is the cultural history of many of these episodes. Their interest extends well beyond the place which they occupy in the pantheon of principled stands against visible religious repression.

In the aftermath of the Napoleonic war, the ideas of Thomas Paine, and the Jacobin-inspired ideology that resulted from them, appeared to be a serious threat to an establishment which viewed Christianity as its vital foundation. Thomas Paine’s ideological heirs slashed away at this cosy conservative view which they believed had impoverished and misled the nation.

The campaigning of Richard Carlile, Mary-Ann Carlile, Jane Carlile and Susannah Wright in the 1820s aimed to educate their readership as much about the fundamental principles of the Enlightenment as they did about opposition to the power of religion. All of them were defendants in blasphemy prosecutions who had campaigned against the restriction of knowledge, and, using their own prosecutions as evidence, castigated those who were convinced that awareness of new ideas would damage society. Such ideas ranged from the possibility of a society without a monarch to the importance of the unfettered right to publish literature even on controversial topics such as birth control. These were all ideas that would empower their predominantly working-class audience. The defences of Wright and the Carliles invoked the argument that access to knowledge was freedom in its purest form. They defiantly argued that if their work to promote such knowledge could be proven to be harmful, they would immediately desist from it. This displayed a touching innocence and trust in the power of knowledge itself, in particular that of science (broadly defined). These were sentiments that inspired the struggle of Wright and the Carliles against irrationality, making sworn enemies of those who would censor knowledge, or confine it to a narrow circle, at the expense of society’s wider collective benefit. Wright and the Carliles also proved that it might be possible, at least in theory, to win arguments in court; indeed, they almost transformed the courtroom into a highly visible stage for advanced ideas. Though defeated, their defence also highlighted the way in which the prosecution’s arguments against them relied on outrage, fear and a compulsion to repress. Such emotions and reactions would not be acceptable to the audiences of succeeding generations.

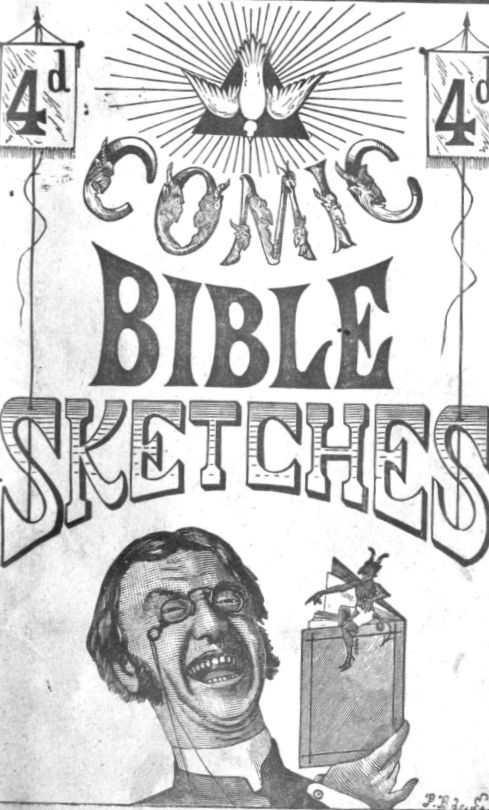

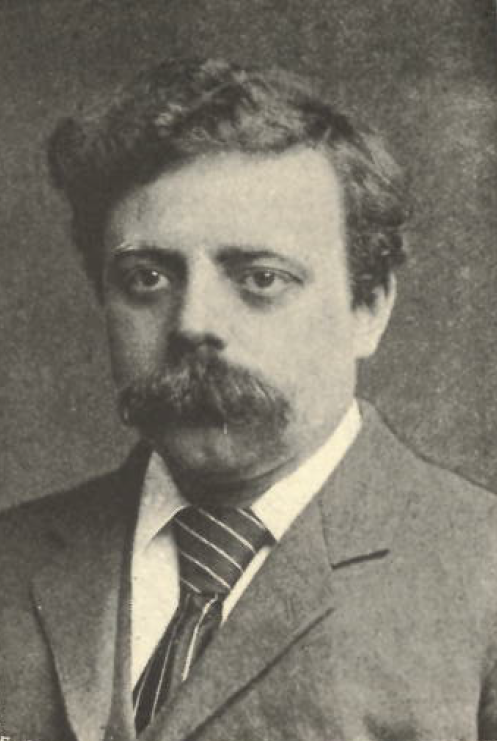

The cases against the Freethinker itself during the early 1880s, and against its editor, George William Foote, and his colleagues, contributed much to the cultural history of freethought that needs remembering. This series of cases spread ripples far and wide. The Freethinker’s assaults on the Bible and Christian doctrine relied on ridicule. Its contributors tried to highlight both the primitive anachronism of the Bible in an age of steam trains and telegraphy, and, simultaneously, the absurdity of some of its stories, which claimed to be the truth underpinning Christianity. The establishment’s version of Christianity and the Home Office prosecutions of Foote and the Freethinker were readily, and easily, painted as contrary to the ‘spirit of the age’, adrift from Victorian modernity.

The Freethinker itself was, moreover, part of a vibrant and widely read mass media, whose content ranged from its own sometimes waspish and scurrilous content, right through to the thoughts of respected literary figures in loftier publications. But even respected literary figures flocked to accuse the authorities of high-handedness; the Freethinker litigation was proof, if it were needed, that the government could no longer speak for, let alone control, public opinion at large. Invoking the idea of the ‘spirit of the age’ had let the discursive genie out of the bottle. The single largest lesson the authorities drew from the case was that interference with published religious opinions, however unpopular or disliked, was likely to be an act of supreme folly. Evidence from the Home Office papers suggests that civil servants, in the years after Foote’s prosecutions, regularly prevented politicians from taking action against content they found offensive.

The Edwardian era saw prosecutions for blasphemy against John William Gott, Thomas William Stewart and Ernest Pack, all members of the Freethought Socialist League in Bradford. Like Foote, these men wrapped their anti-Christian message up in the popular culture of the time, using cartoons, motifs and ideas from popular novels and the music hall. They might well have been left alone at other times, except that their speeches from platforms around the Midlands and the north of England began to attract the attention of local chief constables. The constables became concerned about the circulation of birth control literature at the socialists’ outdoor meetings, as well as about the dangers to public order that might ensue if opponents confronted the inflammatory message of the speakers. Gott, Stewart and Pack also had connections with anarchists, who had become the great bogeymen of the Edwardian era by threatening to bring covert terrorist activity against authority and governmental figures in England as they had overseas. In this tense atmosphere, all three of them were convicted of blasphemy and given gaol sentences. Their agitation and irreverence drifted into the post-World War I years; Gott became the last individual imprisoned for blasphemous libel in 1922. His imprisonment became a particularly unpleasant symbol of repression: during this period, his wife died, and he himself died shortly after leaving prison. Gott’s death seemed to be the final blasphemy prosecution deriving from the Victorian era, and to draw the curtain down upon a century of freethinkers rattling the gates of religious liberty. Public attention for the next fifty years would focus upon the desirability of repealing the blasphemy law and how to do it.

As I have suggested, contemporary cultural trends can spawn blasphemy cases, or create vital contexts that see such cases actively promoted and pursued. This tendency perhaps reached its zenith in the sudden rediscovery of the crime of blasphemous libel in the late 1970s, when the editor of Gay News, Denis Lemon, was privately prosecuted for publishing James Kirkup’s poem, The Love that Dares to Speak its Name, alongside an illustration of Christ with obvious genitalia. The poem also depicted Christ as an active homosexual who had indulged in sexual relations with many characters from the Gospel story. The impetus behind the court case of Whitehouse v Lemon was one notable part of the campaign by Mary Whitehouse, a Christian conservative activist, against the widening and seemingly unstoppable tide of permissiveness which seemed to her to be overrunning the country. Arguably, she lighted upon blasphemy because she had been triumphant in preventing the Danish film maker Jens Jurgen Thorsen from entering the country to make his film The Sex Life of Jesus. But there may also have been a deeper reason: that she, alongside others, felt her religion had been betrayed from within. Every piece of legislation that permitted homosexuality or easier abortion seemingly owed its passage to fearful bishops and accommodating clergy who were falling over themselves to ‘modernise’ after the apparent reverses of new liberal theology. Many Christians, like Whitehouse, felt this had been spearheaded and set running by interventions such as John Robinson’s Honest to God published in the previous decade. Thus blasphemy was invoked by a Christian laity as a way of voicing its concerns that its own hierarchy would sell out its followers to accommodate an unworthy secular world.

The mid-1990s saw Nigel Wingrove’s film Visions of Ecstasy becoming the subject of similar controversy. This film was a dreamlike recreation of religious and sexual ecstasy, as portrayed in the visions of St Theresa of Avila. Wingrove was dumbfounded when the British Board of Film Classification refused it a certificate on the grounds that it ‘might be blasphemous’. He took his case to the European Court of Human Rights, where he initially won, but was subsequently outflanked and defeated by the British government’s invocation of the ‘margin of appreciation’. This provision allowed individual EU nations to retain laws that were essential for the preservation of national culture. Seeing blasphemy laws through this prism suggested they were important to British identity and were a bulwark against some of the worst excesses to which membership of the EU might expose the country. The cultural watchwords of isolation, exceptionalism and perhaps even superiority hung over this result, alongside the chance to view at least nominal Christianity with some sustained and rejuvenated affection.

The abolition of the common law blasphemy offences in England and Wales in 2008, and of similar offences in Scotland in 2021, ended their official history in most of the UK. Abolition of Northern Ireland’s blasphemy laws is under consideration. In the Republic of Ireland, in contrast, new blasphemy provisions criminalising the ‘publication or utterance of blasphemous matter’ were introduced via the Defamation Act 2009. The aim was make the offence apply to all religions, as was perceived to be required by the 37th Amendment to its Constitution. However, these were repealed in 2019, following the results of a 2018 referendum in which over 64 per cent of the electorate voted to repeal the Amendment.

In 2022, then, blasphemy is officially no longer a crime in most of the UK, or in Ireland. Yet in the UK, some critics, including the National Secular Society, and to an extent Humanists UK, have argued that incidents such as the Batley Grammar case, or the cancelling of films and books deemed ‘offensive’ by certain religious groups, risk reintroducing a de facto blasphemy law by the back door. As pointed out by both the NSS and HUK, similar concerns arise with the definition of ‘Islamophobia’ that has been adopted by Labour, which has a tortuous ‘Islamophobia policy’, as well as by the Liberal Democrats and some local authorities.

The sort of pressure exerted by religious groups in Britain today, and their rhetoric of offensiveness, take us back to the world of the eighteenth century, where vested interests could use a blasphemy accusation to prevent material being seen or read. The chilling effect which blasphemy laws had upon public expression prior to the twentieth century seems to be returning by other means in the twenty-first.

David Nash’s latest book, co-edited with Eveline G. Bouwers, is Demystifying the Sacred: Blasphemy and Violence from the French Revolution to Today (De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2022, open access).

Enjoy this article? Subscribe to our free fortnightly newsletter for the latest updates on freethought.

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate