In 2020, Nigerian ex-Muslim and humanist Mubarak Bala was arrested and imprisoned for blasphemy. Thanks to the work of Humanists International (HI) and its partners, Bala’s 24-year sentence was significantly reduced, and he was released on 19 August 2024, having served his sentence—news which has only recently become public.

Former Freethinker editor Emma Park wrote two articles about Bala’s case in 2022, which can be read here and here. These pieces were based on publicly available court documentation and interviews with the head of Bala’s legal team, James Ibor, Bala’s fellow humanist Leo Igwe, and Bala’s wife, Amina Ahmed. They also contained comments from HI President Andrew Copson and HI’s Humanists At Risk Coordinator Emma Wadsworth-Jones.

In August 2023, Bala wrote the following account for the Freethinker. It could not be published then due to safety and legal concerns and so it appears now for the first time. Apart from some very minor edits, it is unchanged. The necessary background to this account can be found in the links given above.

I asked Bala for an update on his situation in January 2025, which I have appended below.

In his 2023 account, he wrote ‘I feel that I may never make it out of jail alive’. Thankfully, he did. On behalf of the Freethinker, I congratulate Bala on his release and applaud his fearlessness. Mubarak, your voice can finally be heard.

August 2023 account

I am now in Abuja Prison after my transfer out of Kano State. I am no longer in a Sharia territory and am largely out of danger, save that individual inmates could take the law into their own hands due to my stance. Abuja is still in northern Nigeria, and the kind of people living in the hinterland—Muslims who appear normal but turn into fanatics the moment a blasphemer or apostate is caught—can still be found here.

Over a year ago, the jail here was broken into, and inmates escaped. ISIS broke it open to free their commanders; I would be in greater danger if they were still here. But the jail seems safe and stable for now.

My forced detention was carried out by the police in Kaduna state, 300 kilometres away from Kano. They then smuggled me into Kano to make it appear that I was arrested there so that the Kano court could have jurisdiction over me. At first, the idea was that I would be persuaded to convert back to Islam. The police began to proselytise me the day after they arrested me. They carried on doing so for three months, using many tactics, including threats of violence—telling me that my location was known by the townspeople—and starvation during the day (it was Ramadan, so I was expected to fast).

I was mostly ill in Kano. I was perfectly healthy when taken in 2020, but my health deteriorated over the 30 months and more before and after the trial. I developed heart and breathing problems and suffered from stress, trauma, sleepless nights, palpitations, fever, diarrhoea, lice bites, heart and kidney pain, skin infections—sometimes on the genitals—typhoid, and much more. My brain tried hard to shut down entirely and block the memory of what was happening. I was living like a robot, trying to pull through in despair.

In Abuja, I was at last able to see medical professionals and receive medical supplies for my ailments. Right now, I am stable. Friends support me with their counsel and funds to secure toiletries and medicine, as well as a better diet that suits my now strict health regimen.

If any Muslims react violently to my words, that is their responsibility, not mine. I have the right to criticise the religion that says that apostates must die. It has killed and still kills.

I wrote a letter to the President of Nigeria, who releases people on amnesty from time to time, even rapists, kidnappers, gun sellers, and murderers. However, this channel was not successful, and I have also been unable to secure release on bail or parole. My appeal in the Federal Court of Appeal is the biggest hope I have now.

It has now been a year and a half since I filed my appeal, and the appeal court has not sat for any of the proceedings. The lawyers say it could be the end of the year before I get a first sitting. The case will take three sessions before judgement can be given. This means that the appeal court may not reach its final decision on my application for bail and challenge to jurisdiction (on the grounds that I was not in Kano state when I published the ‘blasphemous’ Facebook posts and so did not fall under the Kano court’s jurisdiction) until 2024 or 2025.

My strongest argument is that my words are not a crime, and that I am countering Islamism and terrorism. If any Muslims react violently to my words, that is their responsibility, not mine. I have the right to criticise the religion that says that apostates must die. It has killed and still kills.

At the same time, my family is doing great. Here in Abuja they have access to me at weekends. I am able to see my son growing up!

I drafted a few books while I was in prison in Kano, on topics including my life and incarceration, a perspective on northern Nigeria and the country’s place in Africa, global terrorism, humanism, and Islam. I am in the process of refining and reorganising the drafts so they can be published, to serve the purposes of humanism and freedom. My opponents’ goal in incarcerating me was to put me out of circulation. If my words can be published outside, then they will survive and reach others, even if I do not make it out of prison alive.

Why did I plead guilty in my trial before the Kano court in 2022?

In my trial before the Kano court in 2022, I pled guilty to the charges of blasphemy against me, even though I did not think I had done anything wrong. Here are my reasons for doing so:

- I feared that, in the process of the trial, I might say things that would inflame the situation, and they might punish me with psychiatric treatment. Since this would have been a court order no one would have stopped it: I would have been treated as I was in 2014, when my father took me to a doctor because I told him that I no longer believed in Islam. I was never epileptic nor mad but was forcibly drugged, detained in a psychiatric ward, and compelled to fast and pray.

- I was concerned about my safety, both at court and in prison, after the media made my location public. I was also worried about a possible mob in the prison of 2,000 Muslims. From outside the prison, the fence could be scaled easily.

- My mum, siblings, family, and home would not have been safe if I had blasphemed in court—and the readings and proceedings would also have been blasphemous.

- The prison guards would have harmed me back in jail or allowed me to be harmed—they had done so several times already. For instance, they denied me medication for weeks and threatened me if I ate or drank water publicly during Ramadan. There were other, more serious matters that I cannot discuss at the moment.

- My calculations were that it would make the judge more likely to be lenient if I saved them time and resources by pleading guilty.

- My most important goal was to reach the safe custody of a prison in Abuja, which, as the nation’s capital, is a neutral, federal territory.

- I thought I would stand a better chance at challenging the court’s jurisdiction and of obtaining bail at the federal level, on appeal, or in the Supreme Court.

- I thought that if I did not plead guilty, there was a risk that my trial could be repeatedly adjourned as a result of tactical absences by the prosecution. Each adjournment could have been for two months. The prosecution could have done this for ten years if they had wished.

- The barrister who filed a petition against me, S.S. Umar—as shown in the BBC documentary about my case, The Cost of Being an Atheist—clearly wanted to ride on my case to popularity or celebrity, so I cut him off by pleading guilty.

- My health conditions were deteriorating: I needed medical treatment for heart and kidney problems, as well as a toothache.

- I believed that I would eventually get convicted no matter what, whatever semantic games my lawyers could play, however long it took—and the prosecution intended to stretch it out as long as they could.

- In Kano, I had virtually no access to legal and family visits for 24 months.

- In an environment where the judge was not neutral and society was hostile to me, I was sure that the prosecution were desperate. I do not believe they were supposed to take me and detain me without tangible access to lawyers and my family for two years.

- I was forced back into Islam and I hated being in a religion that I had chosen to consciously leave. I hated being forced to practise the compulsory yoga of daily prayers and the starvation called Ramadan.

- I had to protect humanists in Kano and northern Nigeria: the trial was tending towards exposing them and threatening their delicate safety, which I have worked so hard to protect all these years. Two humanists had already died since my arrest in 2020. From stories I was hearing in 2022, many more were in mortal danger and trapped—some with their jobs, others in the matrimonial marriage market, involving a bride price and dowry. In northern Nigeria, simply leaving Islam means you are likely to be killed, you do not need to blaspheme or insult any prophet. The exit or apostasy is enough of an excuse in itself.

The night before my trial, I wrote down my reasons for my intended guilty plea and handed them over to my lawyers and local and international humanist groups on the morning of the trial. My decision was rational and not merely a result of duress and confusion under the pressures of the trial.

How do I feel about my imprisonment?

I am resigned to my fate. I have seen that whenever the Nigerian government wants to punish people for just being themselves, or to actually create conditions that will mean that they end up dead, no one can do anything about it. I cannot fight the government and have no way of securing a fair hearing.

The situation has reached a point where I feel that I may never make it out of jail alive. But at least I have tried, I have spoken, I stood out, stood by my conscience and made a stand—not just for myself, but for people like me, here in Nigeria and all around the world, those who have died, those who are still with their kidnappers, and those whose governments are killing them for their beliefs.

If and when I am released from prison, my goals are to:

- Reorganise the dispersed and demoralised humanist community in Nigeria and to rejuvenate them in our collective quest for freedom of conscience and freedom of expression.

- Seek a proper medical checkup for myself.

- Get another job, or attend school, with whoever is willing to have me.

- Publish my books, when they are fine-tuned.

- Set up many other humanist sanctuaries in other states.

- Be with my family and watch them as they grow. I would take full responsibility for their well-being as well as their safety.

In due course, I aim to join the political arena. This is the only place I believe I can bring about tangible change and make a meaningful contribution to society and to building the nation. We humanists have been on the sidelines: this is why we suffer and have no protection. Who knows whether, in the coming decade, Nigeria may not have as its youngest president someone who is truly secular, ensuring freedom and safety for all Nigerians, irrespective of their tribe, religion, regional advantage, or perceived prestige.

I also intend to lobby the government to recognise humanists as fully participating members of society and citizens. We should not have to live in fear just because our former families and community have ostracised us, thereby impoverishing us economically and socially as well as mentally. Even if we do not receive this recognition from Nigeria, we would greatly benefit from foreign support from individuals, organisations, and governments. All we want, like anyone else, is to live decent, moral, and dignified lives—only without gods or dogma.

Update, January 2025

I had a pronouncement of freedom on 13 May 2024, and I got actual freedom on 19 August 2024. I have used the time to recuperate, visit family, and plan for the future.

I have now focused on my health and my family and I am working on my new reality, starting over at 40, anew, from zero—or, actually, in debt, and with some health challenges accrued over the years. But I shall prevail, I will recover, I won’t give up. It may not be smooth, but I’m determined to succeed in life, against all odds.

I am also looking for partners to publish what I have developed over the years—books, essays, documentaries. This may take a few years to achieve, as will setting up a new media house, with partners providing funding, which I will develop into a global mouthpiece for secularism, especially focusing on sub-Saharan Africa—most importantly, Nigeria, so that I may help change the trajectory of the country, moving it away from the precipice above the abyss of religious fanaticism and turning it into a truly secular state, safe for all.

Finally, in a decade or half a decade, I plan to enter the fray politically, so I can bring about the change I have always dreamed of and probably save my people and country from the abyss I see them falling into, apparently in a trance or sleepwalking—that is, taken over by a mind virus that eats away people’s consciences and destroys nations.

My conviction is also heading to the Supreme Court so that I can claim justice and make sure, once and for all, that no one can be harassed or murdered for leaving a religion or face persecution or violence after accusations of insult or blasphemy. Things shall be set straight.

Related reading

Secularism in Nigeria: can it succeed? By Leo Igwe

Protecting atheists in Nigeria: the role of ‘safe houses’, by Hank Pellissier

A new pact for atheism in the 21st century, by Leo Igwe

Silencing the voice of God: the journey of an evangelical apostate, by Cassandra Brandt

Why I am no longer a Hindu, by Amrita Ghosh

Traditional religion in Zimbabwe: was God a Christian import? By Tauya Chinama

Humanism in Zimbabwe, by Tauya Chinama

The resurgence of enlightenment in southern India: interview with Bhavan Rajagopalan, by Emma Park

Secularism and the struggle for free speech, by Stephen Evans

The need to rekindle irreverence for Islam in Muslim thought, by Kunwar Khuldune Shahid

The Galileo of Pakistan? Interview with Professor Sher Ali, by Ehtesham Hassan

10 years since the Charlie Hebdo attack: a message from the Freethinker, by Daniel James Sharp

Charlie Hebdo: An open letter to the free world from a freethinker, by Khadija Khan

Cancel culture and religious intolerance: ‘Falsely Accused of Islamophobia’, by Steven Greer, by Daniel James Sharp

Surviving Ramadan: An ex-Muslim’s journey in Pakistan’s religious landscape, by Azad

The plight of ex-Muslims in Britain today, by Benjamin Jones

Blasphemy and violence: review of ‘Demystifying the Sacred’, by Adam Wakeling

Britain’s blasphemy heritage, by David Nash

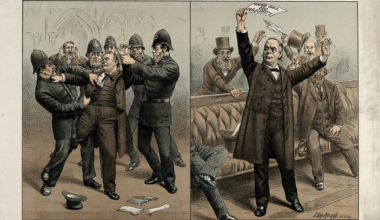

On trial for blasphemy: the Freethinker’s first editor and offensive cartoons, by Bob Forder

The problem with ‘Islamophobia’, by Mark Lilly

Kant vs Tahir Ali: why desecration should not be outlawed, by Daniel Herbert

Three years on, the lessons of Batley are yet to be learned, by Jack Rivington

Is all publicity good publicity? How the first editor of the Freethinker attracted the public’s attention, by Clare Stainthorp

Silence of the teachers, by Nath Jnan

Image of the week: Jesus and Mo on clerical fascism, by Mohammed Jones

Image of the week: Jesus and Mo on identity, by Mohammed Jones

Image of the week: ‘Moses Getting a Back View’ (1882), by Daniel James Sharp

How I lost my religious belief: A personal story from Nigeria, by Suyum Audu

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate