Trains of (Free)Thought is a four-part series of reflections prompted by the author’s travels through France, Italy, Switzerland, and Germany between 26 August and 23 September 2025. Other instalments in the series can be read here. All images are the author’s unless otherwise stated.

A statue of Thomas the Apostle, located deep in the subterranean museum of the Duomo di Milano, catches my eye. It calls to mind perhaps the most acute case of religious doubt recorded in the Bible, which is also one of the most corporeal and sensory moments in sacred history: Having admitted that he does not believe the Resurrection has occurred, Thomas asks to see and touch the bodily wounds of the risen Christ (John 20:24-29).

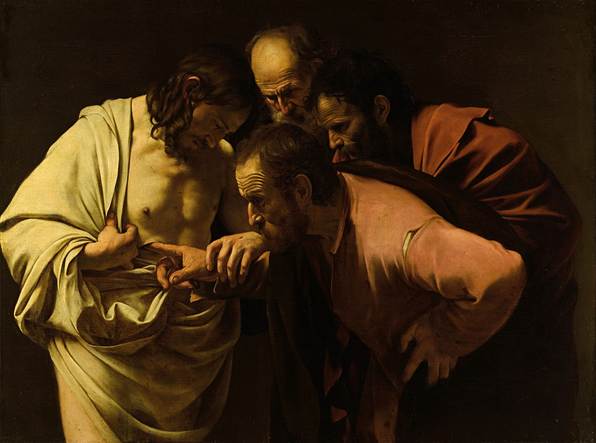

One of the most effective artistic works to portray the ensuing contact and the resulting renewal of the disciple’s faith is Caravaggio’s The Incredulity of Saint Thomas (c. 1601-1602), held in Sanssouci, Potsdam. The oil painting combines dark drama and remarkable simplicity to convey the profound spiritual meaning embedded within an intense moment of materiality. It is one of many efforts to capture the tangible yet ambiguous role of the body and the senses in a scriptural story that has preoccupied successive generations of believers.

While he invited Thomas to touch his wounded body, Christ also offered a reminder to his followers about the primacy of faith: ‘Thomas, because thou hast seen me, thou hast believed: blessed are they that have not seen, and yet have believed.’ Nonetheless, the episode is particularly intriguing for historians of atheism because it suggests that elements of uncertainty, doubt, and incredulity, along with a plethora of related words for the absence, incompleteness, or interruption of belief, are palpably present within religious traditions, not merely as instructive parables, but as formative components of theology and practice that invite people to confront the tension between the world around them and the world beyond. The religious reckoning with non-belief is as old as spirituality itself. Crucially, it is not only embedded within prescriptive doctrinal texts and the cautionary pronouncements of preachers. It is a struggle that preoccupies the laity as well.

Next year will mark the fiftieth anniversary of the original Italian publication of Carlo Ginzburg’s seminal monograph The Cheese and the Worms (1976). The book is partly a response to the work of the French historian Lucien Febvre, who had argued in a seminal case study of Rabelais entitled The Problem of Unbelief (originally published in 1942 and translated into English in 1982), that the pre-modern mind was incapable of intellectually sophisticated unbelief before the Enlightenment. Developing the idea that the oppressive confines of medieval religiosity had ultimately prevented Rabelais from adopting atheism, Febvre suggested that this situation was emblematic of sixteenth-century culture more generally.

Yet, as Ginzburg argues, ‘the argument becomes unacceptable when Febvre turns to “collective mentality (or psychology)” and to the insistence that religion exercised an influence on “sixteenth-century men” that was both restrictive and oppressive and also inescapable, as it was for Rabelais’. In contrast, Ginzburg’s book excavates the intellectual and socio-economic stratification of pre-modern ‘popular culture’, emphasising the irrepressible dimensions of heterodoxy that could shape the lives of ordinary people.

Developing these ideas, Ginzburg investigated the case of a sixteenth-century Italian miller and former town mayor named Menocchio, whose stubborn and vociferous dissent in matters of theology and religious politics drew the ire of the Inquisition.

It is a recurring irony of history that those who try to curtail or eradicate dissent so often turn out to be the most meticulous in preserving evidence of it for posterity. The Inquisitorial record of Menocchio’s interrogation, along with witness statements that several of his neighbours and friends provided, suggests that he had garnered quite the reputation, not only for holding heterodox beliefs, but also for putting them into practice and sharing them publicly. He conjured up his own theory of creation, which revolved around an elaborate yet quotidian analogy according to which angelic beings emerged from earthly matter as worms emerge from cheese.

In place of confessional orthodoxy, he envisaged an egalitarian framework of religious truth based on the notion that God engaged with everyone regardless of religious identity: During his trial, he claimed that ‘the majesty of God has given the Holy Spirit to all, to Christians, to heretics, to Turks, and to Jews; and he considers them all dear, and they are all saved in the same manner’. He also possessed prohibited books, including a vernacular Bible (the contents of which he routinely critiqued), and uttered blasphemy against the saints. Perhaps most dangerous of all, he criticised the hegemony of the priests and suggested that the hierarchical structures of the Catholic Church oppressed the poor.

Like so many other heretics, Menocchio was eventually executed for his recalcitrance. As an historical parable about the consequences of rebellious idiosyncrasy, his life reminds us that believers themselves have been among those to pay the ultimate price for resisting religious authority and thinking independently.

What insights might freethinkers, secularists, humanists, and atheists take away from this episode? There are two major aspects: how we think about believers and how we think about non-believers. Firstly, though it should go without saying, religion does not inherently prevent ordinary people from thinking for themselves. Far from mere conduits for the unfiltered dissemination of doctrinal orthodoxy, believers can and will voice their own opinions on matters of politics, culture, and society, as well as religion itself. Consequently, even the most ardently secular non-believers might stand to benefit from taking religious ideas and arguments more seriously in debates about the direction of our collective civic and moral life.

If freethinkers are to live up to the name, they must surely seek out views that challenge their assumptions and disturb the consensus they have created for themselves. Indeed, is it not an unwritten credo of freethought that contrary opinions are all the more worth preserving and protecting? At the very least, non-believers should refrain from dismissing the perspectives of religious people purely on the basis that they are religious. This tends towards the very dogmatism that freethinkers claim to reject. For their own benefit as much as anyone else’s, freethinkers should make more room for the possibility that religious people have minds of their own.

Then there is the second element: the question not of what non-believers think of religion, but of how we think about ourselves. We might benefit from considering more closely the notion that there is a religious impulse to question, doubt, and create meaning, and that this is different to the corresponding secular impulse. And freethinkers might benefit from learning how this works and how to harness it. In other words, where are our Doubting Thomases? Where are our Menocchios?

This is not to advocate for a sceptical rejection of bodily science or the advent of new secular creation myths, but rather to invite broader questions: what are non-believers getting wrong? Is our moral, cultural and political infrastructure sound? Do we all think too much alike? Are we meaningfully relating to each other, to our bodies, to our sense of existence? What can we offer beyond the realm of theological, philosophical, and scientific debate? How do our ideas impinge upon ordinary lives?

A recent political development in the UK offers a case study in the difficulties we face in order to properly answer these questions. For the record, I have argued elsewhere that there is no compelling reason why so-called ‘assisted dying’, or any other practice that enables the state-sponsored killing of vulnerable people, should have become a natural cause of humanism or secularism, or freethought, or atheism for that matter. The aim here is not to relitigate the debate itself. It is rather to highlight a flaw in the way non-believers are arguing to begin with. Reading the recent statements of Humanists UK and the National Secular Society on the matter, it seems many non-believers are trying to create a new moral and political consensus, complete with policy documents and talking points, that extend far beyond the remit of our shared philosophical position, which is merely that we absent ourselves from religion.

Collectively, these prescriptive tendencies, which have emerged in parallel with the burgeoning of the non-believing constituency over the last few decades, run the risk of replicating the very hierarchies, dogmas, and inquisitions against which previous generations of dissenters and independent thinkers rebelled. Of course, many of these rebels were themselves religious, and they had something important to say. They still do.

Just as believers can benefit from secular wisdom, so too should non-believers engage with the insights, wonders, and mysteries that religion has to offer. The statue in the vaulted museum of the Duomo di Milano provides another example of the age-old effort to render the sacred history of spiritual doubt in material and corporeal terms: it depicts the figure of St Thomas, one hand outstretched, and the other brandishing a Bible.

The policies of the cathedral prohibit unauthorised republication of photographs taken in the museum, and so I cannot share with readers any visual or physical evidence for this monument. You’ll have to take my word for it. After all, ‘blessed are they that have not seen, and yet have believed’.

Related reading

The Right to Die: The Freethinker and the Assisted Dying Debate Over the Years, by Daniel James Sharp

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate