Christopher Hitchens died at an inauspicious time. He was just shy of the full effects of the Arab Spring, the election of Donald Trump, and Britain’s exit from the European Union. Just a few years after that, and you can add the COVID pandemic, the Taliban (re)takeover of Afghanistan, and Israel’s destruction of Gaza. For a man with his breadth of knowledge and historical acuity, he would have produced copious amounts of copy on these events, not to mention hours of speeches and talks.

Fourteen years to the day after his death, determining what he might have thought is necessarily speculative. However, by assessing his written and spoken material, educated guesses can be made as to what his views might have been on certain topics. The question is, in what ways would he have maintained his views, and where might he have been forced to alter them in light of new developments?

As Hitchens himself once said when discussing what George Orwell might have thought about events which took place after his death, ‘with knowledge of his writing one can push it to a certain point’. For instance, Orwell died long before the advent of CCTV and mass digital surveillance, yet it is quite easy to predict that he would have had an instinctive aversion to such authoritarian technologies, seeing in them the Big Brother state, as well as an acquiescent and apathetic population.

The main thing of interest, and the focus of this article, is what Hitchens would have made of America today. In the last two decades of his life, Hitchens came to believe in America as an ‘empire of liberty’, a revolutionary force with the potential to spread democracy across the Earth. Would this view have held up for him?

***

The first area worth exploring is what Hitchens would have made of Donald Trump. Asked once by Brian Lamb on C-SPAN what he thought of Trump, Hitchens joked, ‘Oh please… Well, he’s managed to cover 90% of his head with 30% of his hair… I’m sorry to see he’s lost the Slovenian supermodel, though’. In other words, he considered Trump a buffoon not to be taken seriously. And when speaking of Ross Perot, then running for the presidency in 1992, Hitchens declaimed:

It always makes me suspicious when you have these apolitical businessmen saying, ‘Oh, I just want to put the country back on its feet and restore incentives’. There’s something, frankly, I think, sinister about it, unless the guy’s prepared to say a great deal more about what his political opinions are. For example, has he ever voted before and for whom… [because] it’s much too easy to say, ‘If the country can be run like USA Inc with a real can-do guy…’, there’s a whiff of fascism to that I think.

This short judgment on Perot could easily be applied to Trump, and no doubt it would have been Hitchens’ verdict on him. In fact, it is perhaps the most incisive rejection of Trump’s ‘Make America Great Again’ slogan, despite being made decades before Trump’s first run for the presidency. Hitchens would likely have seen the MAGA slogan as a cheap phrase intended to manipulate Americans into reclaiming what had been lost—or alleged to have been lost. Given his aversion to the reactionary, the slogan would not have impressed him at all. Combine this with Trump’s blatant mendacity, crassness, and illiberal tendencies, and it is easy to see why Hitchens would have rejected the man wholesale.

Further evidence of this is supplied by Trump’s own actions and policies. In August 2025, Trump signed an executive order outlawing the burning of the American flag. Although the Supreme Court ruled in Texas v Johnson (1989) that flag burning was within the ambit of the First Amendment, Trump’s order contravened this in a show of petty authoritarianism. In addition, the arrests of Mahmoud Khalil and Turkish PhD student Rümeysa Öztürk for criticism of Israel show a pattern of behaviour from the Trump administration that seeks to repress free expression. That Öztürk was taken off the street by masked ICE agents—by men who refused to identify themselves or give grounds for her arrest—simply for writing an article shows the level of thuggishness that agents of the state are willing to display now that they are empowered by an administration like Trump’s.

When considering ICE, and the police in general, one must observe closely who they target. In the summer of 2025, there were anti-ICE protests in Los Angeles. An Australian journalist was reporting on the ground when she was deliberately targeted by police officers, who are observed on camera shooting her in the leg with a rubber bullet. Meanwhile, in September, an American journalist was thrown to the ground by ICE agents at a New York City immigration court, while another was grabbed and forced off a lift for no apparent reason. These acts happened against the backdrop of countless others in which people have been taken off the streets, imprisoned, and otherwise assaulted by government agents acting with impunity.

These attacks on the vulnerable and the attempts to intimidate journalists work hand in hand. What’s anecdotally interesting is that the online responses from Trump supporters are jubilant. One of the most common phrases you hear or read is, ‘This is what I voted for’. The violence and nastiness do not deter such people; this is exactly what they want. The cruelty is the point. Perhaps the single best exemplar of this new and open sadism is Stephen Miller, Trump’s White House Deputy Chief of Staff. During the protests in Los Angeles, he told Fox News that ICE would seek to arrest a minimum of 3,000 allegedly illegal immigrants per day. This desire for a minimum number of arrests and the seeming indifference to the risk of wrongful arrests show the Trump administration in its true light. Figures such as Miller do not exist as anomalies in this government but as perfect exemplars of it. It is animated by what can only be described as a Stalinist instinct.

A man like Hitchens, who was instinctively opposed to such naked thuggery and who, perhaps more than anything else, believed in freedom of expression, would not have countenanced any of this.

***

The Democratic and Republican parties are bipartisan when it comes to support for the American empire. The 800 US military bases around the world, the near $1 trillion military budget, and strategic alliances with dictatorships around the world are the proofs of this empire’s existence. Hitchens, in a 1996 C-SPAN appearance, rightly observed:

The American press so often writes about the international arms bazaar as if the United States wasn’t its chief armourer and chief patron and chief manufacturer, as if in fact the United States economy wasn’t in many ways a war economy. A fact that’s so big that it never gets mentioned.

As noted above, Hitchens radically changed his views on America’s role in the world post 9-11, seeing the US as an empire for liberty and an empire of liberty. However, Trump, as a phenomenon, would have challenged his post-9/11 conception of the United States, because Trump so openly strips the idealism away and revels in the nastiness of the American empire. More than any other president in recent US history, he has spoken openly and explicitly about ‘taking out’, eliminating, and killing those who do not comply with US foreign policy. Gone are the days when pretences were given about democracy and freedom.

American foreign policy in Western Asia, for instance, with its sponsorship of Israel’s genocide (under both Biden and Trump) and its illegal bombing of Iran, would have demonstrated to a thoughtful writer such as Hitchens that his view of the US as a revolutionary and positive force was unfounded. Moreover, with his history of solidarity with the Palestinians and his condemnation of Zionism as a ‘stupid’ and ‘messianic’ idea (neither of which changed much even after his post-9/11 turn), it is unlikely that Hitchens would not once again have sided with the victims and opposed Israel’s genocide in Gaza. That this genocide would not have been possible without the support of the United States is a fact so large he could hardly have ignored it.

In 2010, Hitchens wrote that ‘[t]he righteous will evidently never tire of the pelting and taunting of Tony Blair’ and argued that the overthrow of Charles Taylor, Saddam Hussein, and Slobodan Milosevic would one day count amongst the Labour Party’s (and by extension Tony Blair’s) honours. Likewise, in his arguments on the Iraq War, Hitchens often referenced Blair’s 1999 Chicago speech in which the latter outlined his belief in the doctrine of humanitarian intervention. Fast forward a quarter of a century, and we find the Tony Blair Institute working with the Boston Consulting Group and Israeli businessmen on the Trump plan for Gaza’s reconstitution after the end of Israel’s assault.

This proposed restructuring and annexation of Gazan territory for the benefit of the US and Israel is an absurd (and obvious) imperial pretension. From a former PM to the current one, we find Britain, directed by Keir Starmer, participating in Gaza’s destruction, as documented best by the journalist Peter Oborne. Given Hitchens’ positive view of British 21st-century interventionism in the Middle East, this likewise would represent a direct challenge to his worldview. How would Britain’s allegedly noble fight square with its participation in genocide?

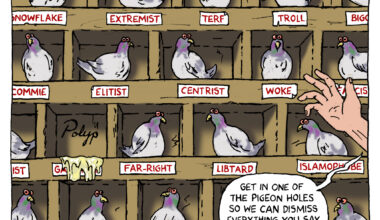

Staying in the Middle East, the most recent development of consequence is the normalisation of Ahmed Al-Sharaa, formerly known as Abu Muhammed Al-Jolani. The entire West has embraced him as the new President of Syria and wiped clean his terrorist slate. This has taken place at around the same time that the majority of the US media and political class has become apoplectic about the election of Zohran Mamdani as Mayor of New York. Mamdani has been smeared as a ‘jihadist’, ‘commie’, and ‘Islamist’, as well as many other insults, simply because of his belief in moderate social democracy. This double standard is not an accident. Al-Sharaa is the new and compliant ally of the West who will not (and perhaps cannot) oppose Israel militarily nor trouble Western interests. The infinitely more reasonable and decent Mamdani, however, threatens the domestic Overton Window on matters of affordability and economic inequality, and therefore he must be caricatured as an existential threat.

In his debate with Michael Parenti on the Iraq War, Hitchens predicted that after the overthrow of Saddam Hussein and the Taliban regime, ‘we will not ever again be finding that we are stuck with a Taliban or Ba’ath-type regime’. The rise of Islamic State from 2014 onwards (as it captured large swathes of Syria and Iraq) and the Taliban’s recapture of Afghanistan in 2021 soundly refutes this prediction. Yet, as noted, the US and Western normalisation with Syria shows that anti-jihadism wasn’t even the point to begin with.

Finally, switching to South America, another example of the United States’ aggressive foreign policy is evident with Venezuela. Republican senator Lindsay Graham has spoken openly of ‘expand[ing] military operations potentially from the sea to the land’, a euphemism for an invasion of the country. This would be an expansion of the current terror attacks being carried out by the US on boats in the Caribbean alleged to be carrying drugs. Lindsay went on to say it was ‘time for Maduro to go’, citing the Monroe Doctrine, the US’s explicitly imperial policy of policing the Western Hemisphere. Trump, meanwhile, believes that Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro’s ‘days are numbered’. Despite all this, Trump has declared himself the ‘peace’ president, a true testament to Orwellian doublespeak, and one which has been taken up by his fanbase. Such reversions to naked imperialism would hardly have struck Hitchens as further adventures in democracy and freedom.

***

The developments of the early 21st century have completely destroyed Hitchens’ conception of the US as an ‘empire for liberty’. An honest examination of the facts, were he still alive, would have likely forced him to the conclusion that he had led himself astray about the nature of the US. Hitchens’ shift from socialism to liberal interventionism partly explains this change. He came to see the US as the world’s centre of revolutionary potential, having lost any hope or belief in the revolutions of the 20th century. However, this view of the US as the positive and revolutionary force in the world has proved illusory and, instead, the country has conformed more conventionally to the great power politics that all empires are subject to. Hitchens, under the weight of the facts at hand, would likely have capitulated to this reality.

Where would he have gone from there? One brief, intriguing thought: would he, returning to his earlier socialism, have been a fan of Zohran Mamdani?

Interesting questions indeed, perhaps for another day.

Related reading

Christopher Hitchens’s Theory of Historical Progress: A Cruel Moral Calculus, by Zwan Mahmod

Christopher Hitchens and the value of heterodoxy, by Matt Johnson

Christopher Hitchens and the long afterlife of Thomas Paine, by Daniel James Sharp

The end of American idealism, by Matt Johnson

1 comment

Bring back Christopher Hitchens!

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate