Books From Bob’s Library is a semi-regular series in which freethought book collector and National Secular Society historian Bob Forder delves into his extensive collection and shares stories and photos with readers of the Freethinker. You can find Bob’s introduction to and first instalment in the series here and other instalments here.

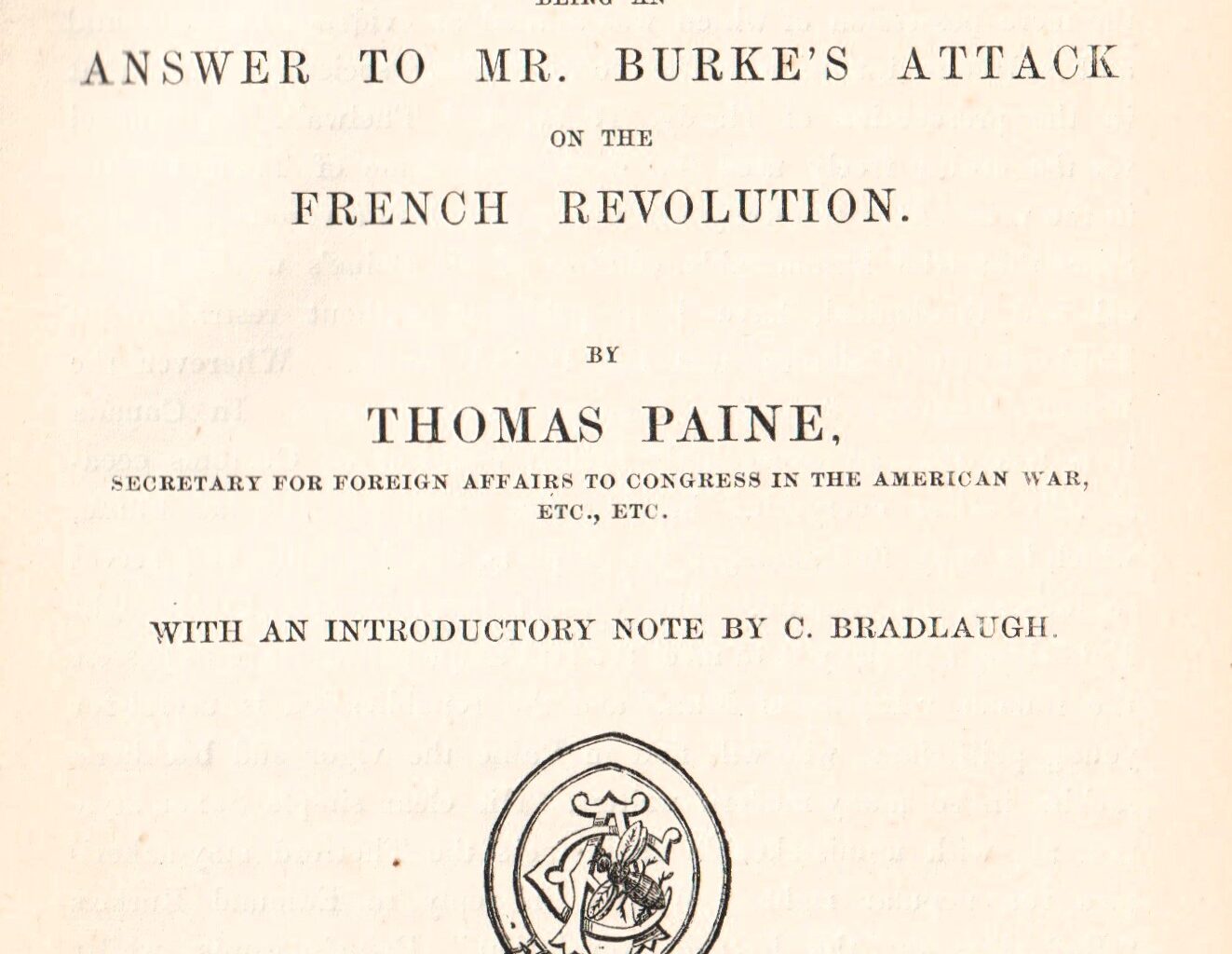

The first article in this series focused on Thomas Paine’s The Age of Reason (three parts, 1794, 1795, and 1807), the last of what Eoin Carter in this magazine recently called Paine’s three ‘era-defining texts’. But I don’t think I should leave Paine without acknowledging the huge significance of his Rights of Man (two parts, 1791-2) to freethinkers—and, in fact, to anybody on what might be loosely described as the progressive side of politics.

In Rights of Man, Paine makes the case that individuals have rights intrinsic to their humanity, independent of the whims or ambitions of political leaders. Individuals are citizens, not subjects, and citizens exercise rights independently of the supposedly God-given authority of aristocrats and monarchs. Here is the case for human rights as a secularist issue (and the reason that this writer regards republicanism and secularism as closely intertwined). For Paine, government must surely be based on the consent of the governed.

Rights of Man was a direct response to Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), an attack on the French Revolution and the British radicals who admired it, and who in some cases regarded it as a blueprint for Britain. The tract tore into monarchy, traditional social institutions, and the hereditary principle in favour of a thorough-going liberal democracy.

Part 1 was originally to be published by Joseph Johnson, but Johnson withdrew from the project following several visits from government agents, correctly sensing that the book would attract bitter controversy. Paine reacted quickly and transferred the work to J.S. Jordan, who was made of sterner stuff, and the book appeared on 16 March 1791. It became an instant bestseller, with around 50,000 copies in circulation by May, albeit at the relatively high price of three shillings. Numerous editions followed and cheaper ones boosted the book’s circulation, leading Paine to boast that it had outsold anything published in recent years, if not ever.

Jordan published Part 2 the following February with a circulation exceeding even that of Part 1. Close to a million and a half copies were sold in Britain during Paine’s lifetime. By now the furore Paine had provoked was reaching fever pitch, with the flames further fanned by a vicious campaign of slander headed by the Prime Minister, William Pitt. While the consequences for Paine were unpleasant, it seems that the attention Pitt and others drew to Paine’s work only boosted sales. In fear for his life, Paine fled the country in 1792 and headed to France, where he received a hero’s welcome. Back in England, his effigies burned brightly and he was convicted, in absentia, of seditious libel against the Crown.

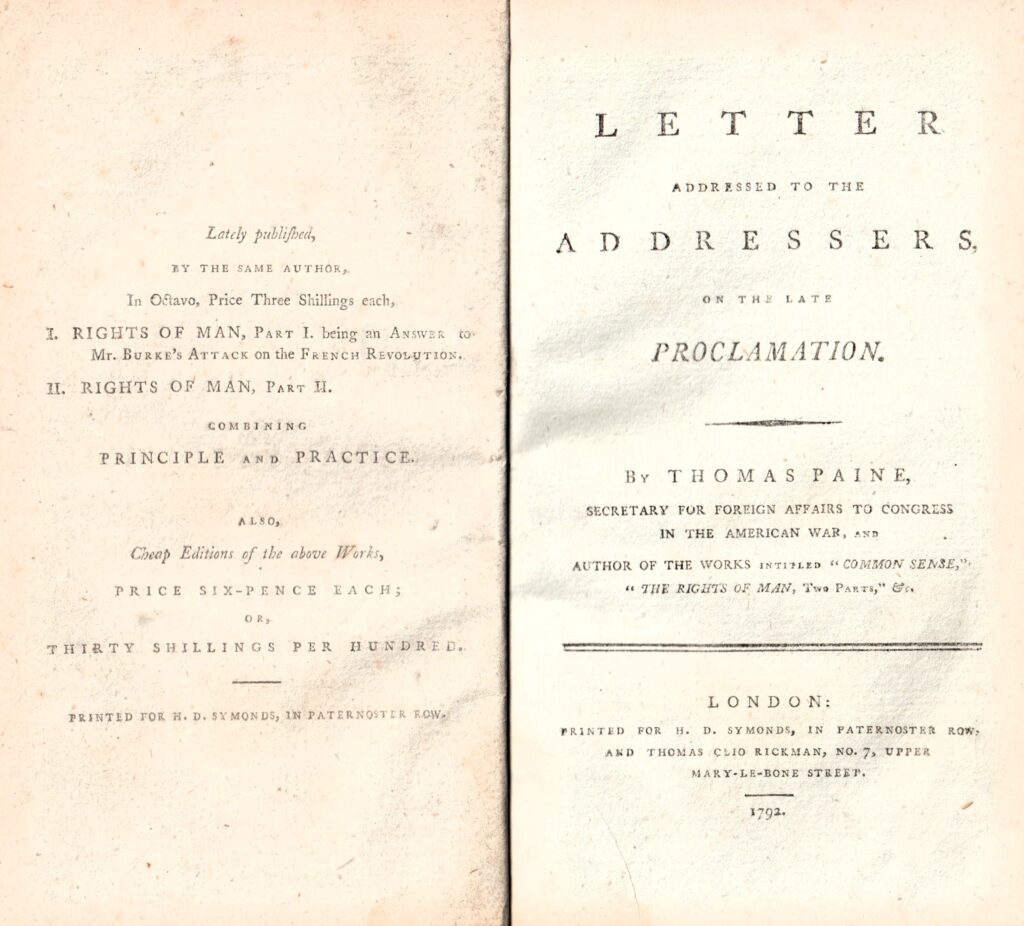

Shortly before leaving, Paine had penned the obscurely titled Letter Addressed to the Addressers on the Late Proclamation, which has been described as ‘practically a third part of Rights of Man’. This brief tract dealt with the issue of how the principles of Rights of Man could be implemented. Paine argued for the establishment of a national convention since a corrupt House of Commons and a hereditary House of Lords and monarchy could hardly be trusted to reform themselves. In some ways, this tract was the most inflammatory and radical of all.

Unfortunately, Jordan’s courage was exhausted and he withdrew from publishing Paine’s works following threats of a sedition charge. At first, Paine took over publication himself under the imprint ‘the printers and booksellers of London’, but when he fled England, he placed it in the hands of H.D. Symonds, who not only published the two parts of Rights of Man but did so in cheap editions at sixpence each. Symonds, in concert with Thomas Clio Rickman, then went on to publish the Letter at the low price of fourpence. Both Symonds and Rickman were persecuted for their trouble, with Rickman following Paine by fleeing to France and Symonds being gaoled for two years.

Paine’s work circulated in huge numbers among the population despite the government’s best efforts to suppress it and it remains in print to this day. I have heard it said that Paine is largely forgotten, and it is certainly true that many, particularly the very religious, would prefer that this were the case. But even if the man is forgotten, his ideas live on and still influence the character of political discourse. It is extraordinary how salient Paine remains. Over more than two centuries, different individuals have alighted on different aspects of Paine’s work which support their own opinions and/or campaigns. Over the years, Paine’s work has been published in various editions by various people. I have several of these in my collection, and their preliminary remarks demonstrate the many uses to which Paine’s work has been put over the years.

Richard Carlile wrote a preface to his 1820 edition of Paine’s Political and Miscellaneous Works from Dorchester Gaol, where he was serving a sentence for blasphemy and seditious libel. He alights on Paine’s ‘[exploding of] the idea of hereditary right in priests, nobles, and princes, and hereditary wrong in the people.’ To Carlile goes a large share of the credit for keeping Paine’s writings alive during the first thirty years of the nineteenth century—a period of severe government repression in the wake of the French Revolution and the fear that the radical contagion could spread across the Channel.

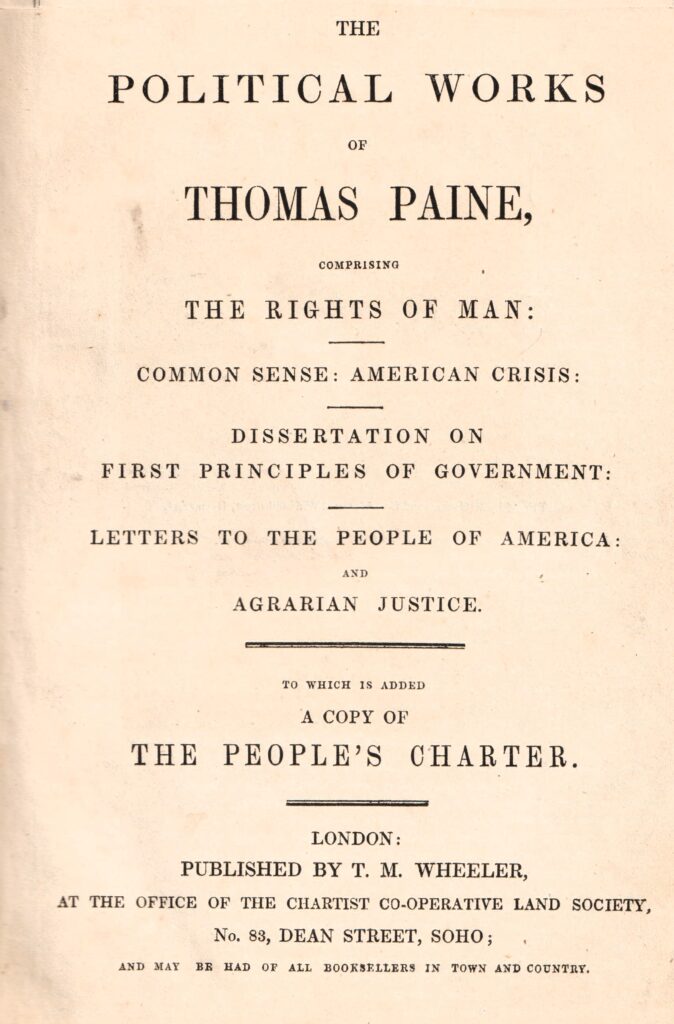

I also have an edition of The Political Works of Thomas Paine ‘published by T.M. Wheeler, at the Office of the Chartist Co-operative Land Society’ (c. 1843), in which a copy of the People’s Charter of 1838 is also bound. The preface presents Paine as an antidote to ignorance which, according to the author, holds millions in subservience and poverty. Paine inspired the Chartists in their struggle for constitutional reform.

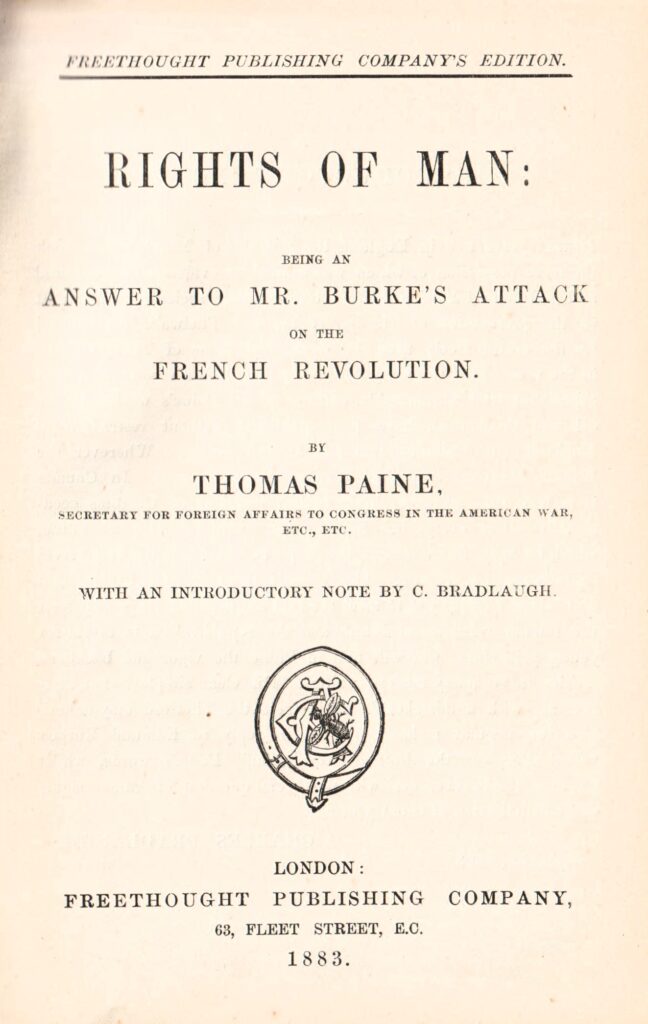

In my collection, there is also an 1883 Freethought Publishing Company edition of Paine’s work with an introductory note by Charles Bradlaugh, the leading secularist, republican, and freethinker of his age, and the founder of the National Secular Society (NSS). He suggests that this edition would be useful for young politicians, who would find Paine’s ‘simple Saxon style’ containing ‘vigour and backbone’ worth imitating. (How very Bradlaugh those words are!) For many years the NSS celebrated Paine’s birthday on 29 January—a sort of freethinkers’ Christmas. (For more on the Freethought Publishing Company and its premises at 28 Stonecutter Street, London, see my previous article on the subject.)

In 1891, the Freethinker founder G.W. Foote’s Progressive Publishing Company published a centenary edition of Rights of Man. This edition contained an introduction by J.M. Wheeler, a close friend of Foote’s, sub-editor of the Freethinker, and a keen student of freethought, whose illness and early death cut short his ambition of writing a history of the subject. Wheeler characterises Paine as ‘the plague of princes’ and describes him as the ‘best-abused man of a century ago’. He gives him credit for his influence on ‘the popular mind’ and for expressing the widespread desire for freedom of thought and expression.

Watts and Co. republished Rights of Man in a Thinker’s Library edition in 1937 for the Rationalist Press Association. In his introduction, the socialist G.D.H. Cole latched upon Paine as a champion of the poor and approved of his belief ‘in using the State as a practical instrument for the promotion of the welfare of its citizens’, dependent on ‘complete democratic equality’ and ‘democratic representation’.

Various shades of radicals, liberals, reformers, and democratic socialists have alighted on rather different aspects of Rights of Man—and Paine’s work more generally—over the years, but it seems to me that for those who strive for a better, more democratic, and fairer world, this old but strangely current book remains a touchstone, whether the man who wrote it is recognised or not. As G.W. Foote often remarked, it is ideas that change the world rather than votes.

Further reading

Image of the week: ‘The world is my country, to do good my religion!’ by Bob Forder

Introducing ‘Paine: A Fantastical Visual Biography’, by Polyp, by Paul Fitzgerald

Christopher Hitchens and the long afterlife of Thomas Paine, by Daniel James Sharp

‘There is nothing easy or empty about humanity and reason’: in memoriam Jim Herrick (1944–2023), by Bob Forder

From the archive: ‘A House Divided’, by Nigel Sinnott

Image of the week: ‘Wha wants me’, a caricature of Thomas Paine by Isaac Cruikshank (1792), by Daniel James Sharp

From the archive: imprisoned for blasphemy, by Emma Park

Charles Bradlaugh and George Jacob Holyoake: their contrasting reputations as Secularists and Radicals, by Edward Royle

Is all publicity good publicity? How the first editor of the Freethinker attracted the public’s attention, by Clare Stainthorp

On trial for blasphemy: the Freethinker’s first editor and offensive cartoons, by Bob Forder

Secularism and the struggle for free speech, by Stephen Evans

Review of ‘A Dirty, Filthy Book’ by Michael Meyer, by Bob Forder

Britain’s blasphemy heritage, by David Nash

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate