Editor’s Introduction

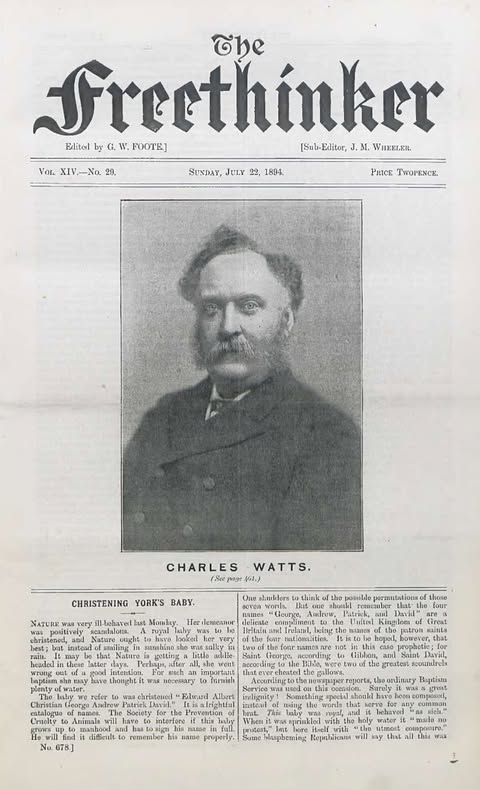

On 10 February 2025, I spoke to the Dundee Humanist Group about some of the history and themes of the Freethinker. Especially for the event, I looked through our historical archive for Dundee-related material, and I found some interesting things. Thus the talk included a ‘Dundonian Addendum’. (That archive dive also inspired a piece on Charles Watts, which includes a reprint of an 1894 article by Watts: ‘From the archive: ‘Secularism contains the real elements of a progressive civilisation’, by Charles Watts‘.)

It was my first time in Dundee and, though I didn’t get to see much of it, I hope to return one day. The Dundee Humanists were a lovely and engaged bunch. On my way to the venue for the talk, I managed to slip in some mud in the middle of the road, so I was a bit dirty and dishevelled when I arrived. Just my luck! But an ill omen it was not; everything went swimmingly after that.

Below is an edited version of my talk, Dundonian Addendum and all, which I have taken the liberty of sprucing up. I have also added a little to it. The footnotes are extraneous to the talk as intended to be given. Thanks again to the Dundee Humanists for having me.

The Freethinker: Some History and Themes (With a Dundonian Addendum)

Thanks very much for having me here tonight to talk about the Freethinker magazine. It’s my first time in Dundee, as it happens. I confess that for years now, the first thing that has come to mind when I think of Dundee is jute. But I delved into the Freethinker archives especially for this occasion, hoping that there would be some interesting Dundee material in there. And indeed there was—worry not, there is a Dundonian Addendum to come.

First though, the Freethinker. What follows relies heavily on various articles on our current website and in our archive and (especially) Jim Herrick’s 1982 centenary history of the magazine, Vision and Realism: A Hundred Years of The Freethinker. [These sources are listed near the bottom of the page.]1

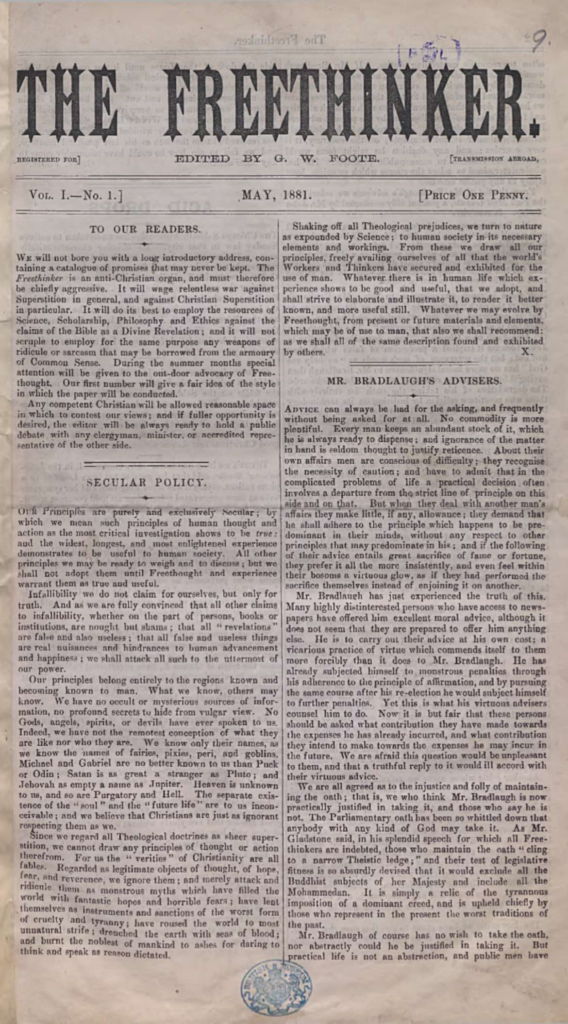

The first page of the first issue of the Freethinker, published 1 May 1881, contained this militant and stirring call to arms from George William Foote, founder of the journal:

We will not bore you with a long introductory address, containing a catalogue of promises that may never be kept. The Freethinker is an anti-Christian organ, and must therefore be chiefly aggressive. It will wage relentless war against Superstition in general, and against Christian Superstition in particular. It will do its best to employ the resources of Science, Scholarship, Philosophy and Ethics against the claims of the Bible as a Divine Revelation; and it will not scruple to employ for the same purpose any weapons of ridicule or sarcasm that may be borrowed from the armoury of Common Sense. …

Any competent Christian will be allowed reasonable space in which to contest our views; and if fuller opportunity is desired, the editor will be always ready to hold a public debate with any clergyman, minister, or accredited representative of the other side.

This opening shot is of interest for several reasons. Its focus on ‘aggressive… relentless war’ is redolent of a longstanding tension in freethought/secularist/humanist circles: to what extent should we be destructive rather than constructive? Is it enough merely to tear down religion? Humanists, in particular, and especially these days, tend to think in a more constructive mode, perhaps, but the question of how to balance the positive and the negative remains, and has been discussed in the Freethinker itself many a time over the years.

Indeed, somewhat belying the militancy of his 1881 salvo, Foote wrote in 1882:

Christians are perpetually crying that we destroy and never build up. Nothing could be more false for all negation has a positive side, and we cannot deny error without affirming truth. But even if it were true, it would not lessen the value of our work. You must clear the ground before you can build, and plough before you can sow. Splendour gives no strength to an edifice whose foundations are treacherous, nor can a harvest be reaped from fields unprepared for the seeds.

He finished off with an even more positive flourish:

The only noble things in this world are great hearts and great brains. There is no virtue in a starveling piety which turns all beauty into ugliness and shrivels up every natural affection. Let the heart beat high with courage and enterprise, and throb with warm passion. Let the brain be an active engine of thought, imagination and will. The gospel of sorrow has had its day: the time has come for the gospel of gladness. Let us live out our lives to the full, radiating joy on all in our circle, and diffusing happiness through the grander circle of humanity, until at last we retire from the banquet of life, as others have done before us, and sink in eternal repose.

So, from early on, the Freethinker was devoted to ruthlessly combating religion, especially Christianity, as well as ‘diffusing happiness through the grander circle of humanity’—a phrase that I think any humanist would be glad to adopt as a motto. This dual mission was nicely evoked by Jim Herrick in 1982: ‘The vision and realism of the twofold secularist programme—countering religion and constructing reform—are as relevant as ever for the next 100 years of the Freethinker.’ This ‘twofold programme’ still, to an extent, describes the Freethinker’s purpose today.

The opening statement is also interesting because it signifies an evolution in Foote’s own thinking. Born in 1850, Foote was a lover of literature and a giant in the freethought world for nearly 50 years, writing, speaking, and editing from the late 1860s until his death in 1915. He was an admirer of Charles Bradlaugh, founder of the National Secular Society (NSS), which he joined, but he came to find Bradlaugh too authoritarian as a leader and too militant in his attacks on religion. In 1876, Foote was expelled from the NSS for his criticisms of Bradlaugh and became involved with a short-lived NSS rival, the British Secular Union.

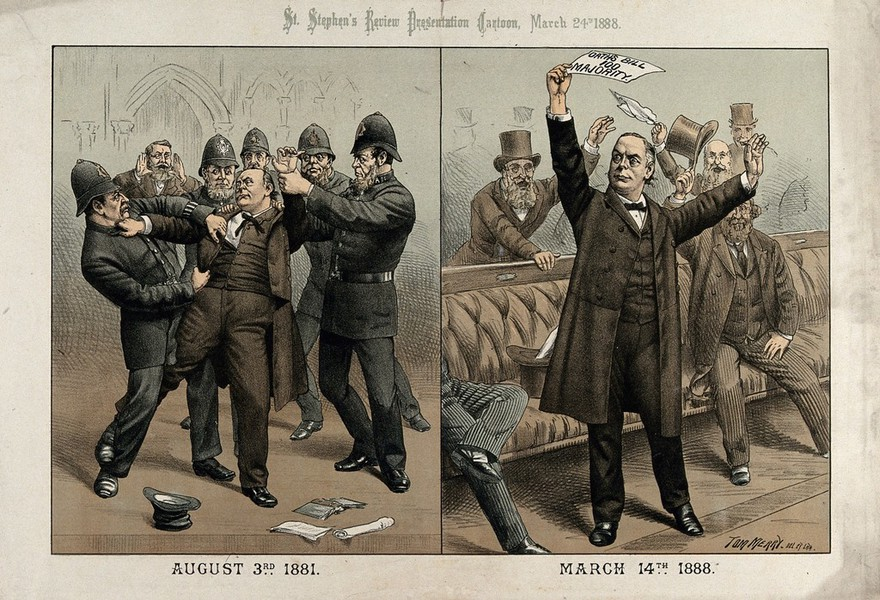

So how did this moderate freethinker end up founding a journal dedicated to waging ‘relentless war’ on Christianity? The answer is simple: he saw, and was disgusted by, the persecution meted out to Bradlaugh by the British state. The full story of Bradlaugh’s troubles with the British Parliament would take us too far afield, but the essence is this: he was prevented several times from taking the seat he had been elected to on account of his outspoken atheism. In 1880, he was even arrested and imprisoned overnight in Big Ben’s Clock Tower for refusing to withdraw from Parliament (he was, incidentally, the last MP to whom this was done—though who knows what the future holds?).

Bradlaugh would eventually take his seat in 1886 after years of campaigning which ruined his health and led to his early death in 1891. His struggles made an indelible mark on Foote, however, and the two men were reconciled. Foote rejoined the NSS and would succeed Bradlaugh as NSS President in 1890, thus inaugurating a long period during which the Freethinker was almost the official mouthpiece of the NSS, though they remained, and remain, separate and independent entities.

Foote was radicalised by the persecution of Bradlaugh, and that is why he founded the Freethinker as a militantly anti-religious publication. The early Freethinker contained scathing, and sometimes repetitive, attacks on Christianity and the Bible. Herrick is perhaps slightly unfair to say that ‘The impudence and sense of excitement at castigating and tearing apart the Holy Writ are no longer easy to appreciate’, but he is right to note that ‘the [Bible] smashing must have been part of the excitement for the first two decades of the Freethinker’s history.’

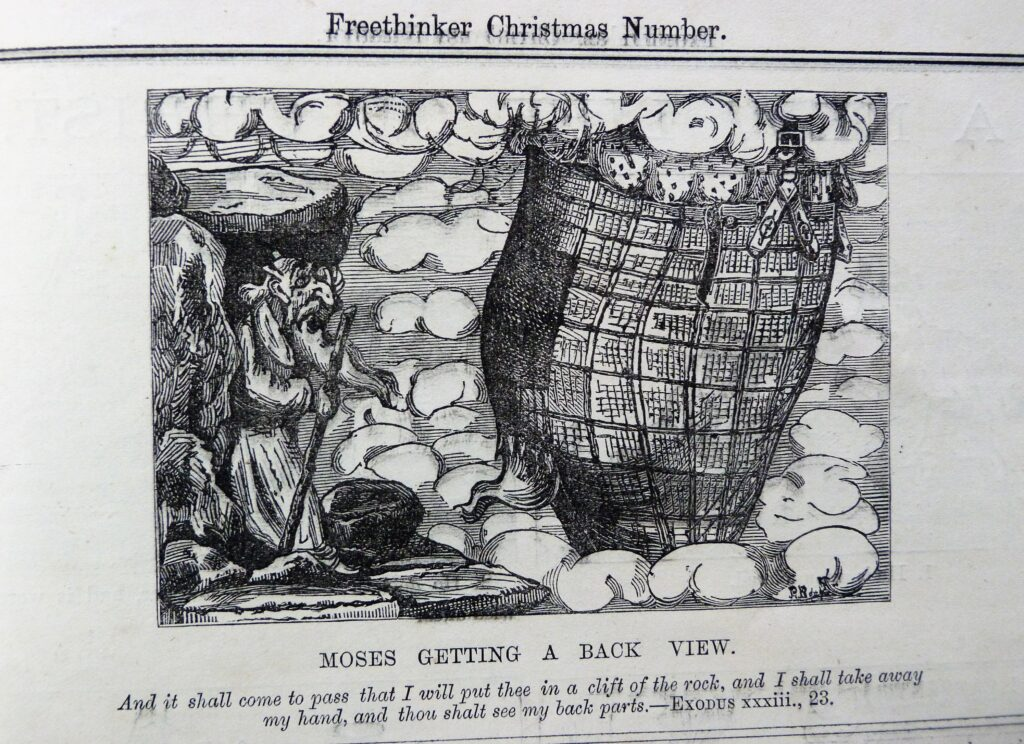

Remember: this was a time when attacking Christianity could come with terrible consequences, as Foote himself discovered when he was imprisoned in 1883 for blasphemy alongside W.J. Ramsey and E.W. Whittle, the Freethinker’s manager and printer, respectively. The Freethinker’s offence was to have published blasphemous cartoons in its Christmas 1882 special issue, including ‘Moses Getting a Back View’, which riffed on the text from Exodus: ‘And it shall come to pass that I will put thee in a clift of the rock, and I shall take away my hand, and thou shalt see my back parts.’ The title of the cartoon is self-explanatory. It might not sound too shocking or subversive now, but it was enough to land Foote in prison for a year, and, as the recent tenth anniversary of the Charlie Hebdo attacks reminded us, the faithful are nothing if not sensitive to the point of slaughter. Words and cartoons, then as now, are a risky business.

The judge at the blasphemy trial was a Catholic bigot named Lord Justice North, and he had it out for the defendants from the start. Foote provided his own defence, speaking for hours at a time in defence of free speech. His last words to the jury included the following:

[A]llow us to go away from here free men, and so make it impossible that there ever should again be a prosecution for blasphemy; and have your names inscribed in history as the last jury that decided for ever that great and grand principle of liberty which is broader than all the skies; which is a principle so high that no temple could be lofty enough for its worship, so broad that the earth could not afford a foundation for it, which is as wide and high as the heavens,—that grand principle which should rule over all—the principle of the equal right and liberty of every man.

This lofty rhetoric failed to save Foote and his colleagues from a guilty verdict, and off to prison they went—but not before Foote got the last word. Upon North’s pronouncement of the defendants’ sentences, Foote retorted: ‘My Lord, I thank you, it is worthy of your creed.’2

Foote was treated quite poorly in prison. Initially, he was given only the Bible to read (this prompted the defiant reflection from Foote that ‘Searching the Scriptures was the best cure for believing in the Scriptures’) and was held in solitary confinement for 23 hours of the day. After a few months, he was given more privileges and was even allowed to write letters to the Freethinker for publication (the magazine was being run in his absence by Edward Aveling). From one such letter:

What plagues me most is a miserable lassitude proceeding from the enforced disuse of my faculties. No writing articles here, no public speaking, (in fact I scarcely utter twelve words a day), no delight of battle; nothing but a lifeless monotony, in which the hours crawl by like an endless funeral procession. Yet my brain is still as vital as ever, for it swarms with ideas, and my heart is stout.3

Campaigns which included support from the likes of T.H. Huxley, Leslie Stephen, and Herbert Spencer for the remission of Foote’s sentence were unsuccessful, and it was not until 25 February 1884 that Foote was released. His last prison letter, from December 1883, shows his undaunted spirit:

We are engaged in a war in which there can be no treaty or truce. Our policy is clear. De l’audace; et encore de l’audace, et toujours de l’audace… [‘Boldness, and again boldness, and always boldness’, from the French revolutionary George Jacques Danton.]

Upon regaining his freedom (he was greeted upon his release by a crowd of 3,000 according to Aveling), Foote went straight back to work at the Freethinker, his militancy undiluted. He published a cheeky open letter to Lord Justice North, explaining that he would continue on his infidel path:

Such is my obstinacy! Such is my appreciation of the Gospel of Holloway Gaol! I can only throw myself on your indulgence, and hope you will not relax your noble efforts to convert infidels to the true faith. And in order that you may not lose any opportunity of exercising your generous qualities, I leave this number of the Freethinker at your house with my card.

I don’t know how, or if, North reacted to this, but one wonders whether he stopped to peruse the pages of the number or just consigned it to the fire.

In any case, the Freethinker survived, and it continued to attack Christianity, promote science and philosophy, address major issues of the day from its ‘radical secularist outlook’ (Herrick’s words), and champion progressive social reforms such as secular education, republicanism, and women’s rights while opposing war and imperialism. (Many of these early subjects have remained a constant, particularly education and republicanism. In fact, a 1982 letter in the Freethinker led to the birth of Republic, the UK’s foremost anti-monarchy group.4) It also kept up its commitment to free speech, criticising censorship and blasphemy laws and coming to the defence of those who fell afoul of them. From early on, the Freethinker was an internationalist publication. In particular, it was concerned with India, celebrating freethought advances there from as early as June 1881. This interest in India has remained pretty consistent through to the present; see, for example, our 2022 interview with the Indian secularist filmmaker Bhavan Rajagopalan.

(Bradlaugh, incidentally, was known in Parliament as the ‘Member for India’ due to his staunch support of India’s interests, and Bradlaugh Hall, which still exists, was erected in what is now Pakistan in memory of the great secularist in the years after his death.)

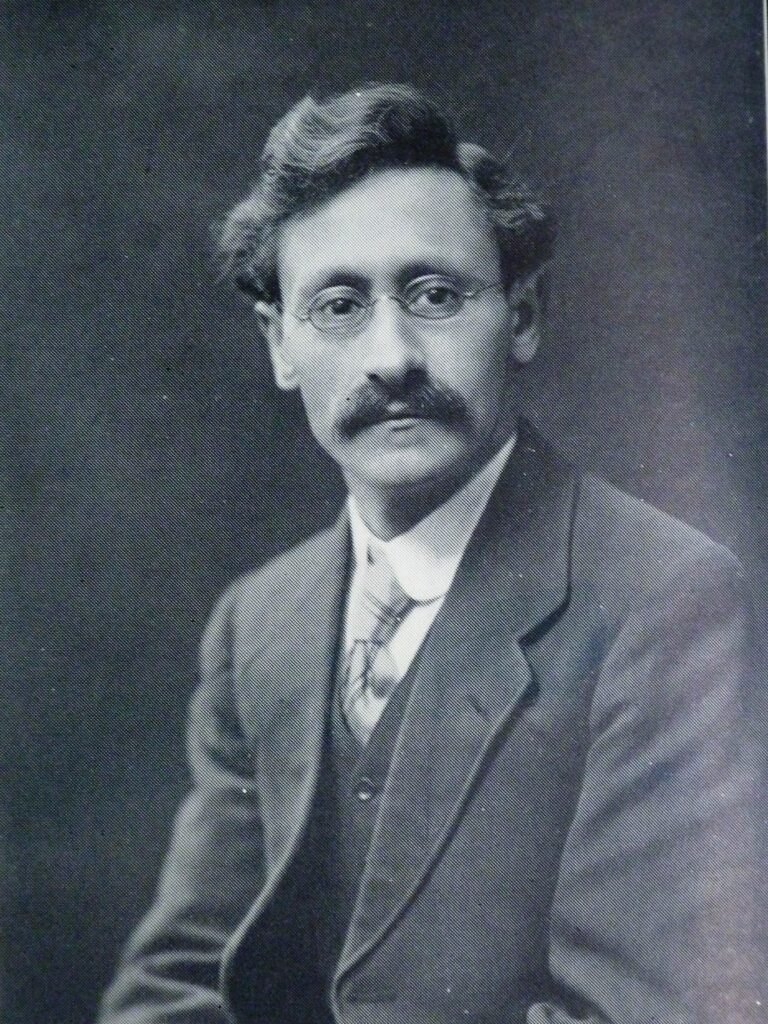

One of the exceptional things about the Freethinker during its first 70 years was the longevity of its editors. Foote edited the publication until his death in 1915. Then his sub-editor Chapman Cohen, who had been contributing to the magazine since 1897, took over, remaining in the role until 1951, just a few years before his death in 1954. Since then, editorial reigns have been much shorter. For its first 70 years, the Freethinker had two editors; over the next 74 years, taking us up to the present, it has had around 20. Only two of those editors have come even remotely close to the reigns of Foote and Cohen: William McIlroy (1981-1992) and Barry Duke (1998-2022). Barbara Wootton, in her foreword to Herrick’s history, probably explained this high turnover best as ‘largely owing to the difficulties of a paper which emphatically requires full-time service for a modest remuneration.’

Cohen was more philosophically inclined than Foote and preferred to take a more detached, anthropological perspective on religion, but he was no less committed to the secularist cause. Attesting to the close relationship between the Freethinker and the NSS, Cohen also succeeded Foote as President of the latter, a role he held until 1949. The link between the Freethinker and the NSS was probably at its strongest in the Foote and Cohen years, though some future editors also served as NSS Presidents and the two have retained close ties to the present day, though now we are more distinct than we have ever been. This, I think, is to the good: the Freethinker should have friends but, in Herrick’s words, it should always ‘[retain] a sturdy independence and right to ignore any party line.’

During the First World War, the Freethinker did not take a dogmatically pacifist stance, but it condemned jingoism, anti-German xenophobia, and censorship in the name of wartime safety and stood up for the rights of nonbelievers in the military. A letter to the Freethinker from Bertrand Russell in 1916 criticised the way conscientious objection was handled by the state: it seemed that only the religious, Russell complained, were allowed to appeal to their consciences when it came to deciding whether or not to take part in the fighting. Despite difficulties caused by paper shortages, the Freethinker was determined to survive the war, and it did. Per Herrick: ‘Determination to “keep the flag flying” [see below for the source of this quote] in opposition to censorship and to sustain a voice of reason at a time of war, when many journals vanished, upheld the Freethinker during the war years.’

The Freethinker had to contend with attempted government interference and pressure to conform to a certain line on the war. As Cohen recalled in 1931:

Just at the beginning of 1916 I received a visit from two men who professed to be Freethinkers and business men in the City. I did not know them, nor could I find out, from their conversation, any Freethinker who did. But they professed a great interest in the paper, and thought that the time had arrived when it might be turned into a company, and they were willing to purchase. I listened to what they had to say, and was doubtful whether I had to compliment them upon their business philanthropy or sympathise with their financial folly. I found afterwards that one at least of the two was a government agent. He came into notice through inciting a Derbyshire school teacher to concoct a fantastic plan to poison Lloyd George, and then acted as an informer.

Herrick takes up the tale:

[Cohen] received a suggestion that he submit [certain] paragraphs for censorship. “I replied curtly that there never had been a censor in the Freethinker office, and so far as I was concerned I had no intention of setting one up.” On another occasion when two men in military uniform requested to see the Freethinker’s subscribers list, Cohen refused and when he was asked if he took any care to see that the paper did not get into enemy hands retorted “Not the slightest.” “I said if the Emperor of Germany sent along twopence half-penny for the Freethinker, it would be posted to the address given.”

Magnificent.

Cohen refused to bow to those who wished to see the Freethinker champion war, making clear that the magazine took no line on the war and was concerned only with ‘[keeping] men’s heads level, and [seeing] that feelings of common decency and justice were not completely forgotten.’ He continued:

Moreover, Freethinker readers had not been accustomed to finding in the paper only that with which they were in agreement. The Freethinker might die, but if it died it would go down with its flag flying, true to both its name and its policy.

Hear, hear! It is pleasing to see my own editorial philosophy so forcefully put by the great Chapman Cohen. His defence of free speech even in wartime could also hardly be bettered. From Herrick again:

Cohen disapproved of any suppression of public debate: “… is it a good thing that political and social disputes should cease and the community satisfy itself with the uniform monotony of a hive of bees?” (25 October, 1914.) When clerics reported a reduction in internal strife as a benefit of the war, Cohen wrote: “Party politics and social conflicts and feminist agitation were at least disputes about the better ordering of social life. It is along that road—the path of discussion, agitation, and experiment—that progress lies.” (2 January, 1916.)

When one reads this sort of thing, it is difficult not to punch the air and yell, ‘Yes, exactly!’ Up with argument and strife and agitation and down with conformity and silence and censorship, self-imposed or otherwise.

One of Foote’s great triumphs came just months before his death in October 1915. He had created Secular Society Ltd (SSL) (confusing, I know—nothing to do with the NSS) in 1898 to evade the legal difficulties brought about by a law which allowed for bequests to organisations which pursued illegal aims, like blasphemy, to be voided. In 1915, and again in the House of Lords in 1917, the legality of SSL and therefore a bequest to it which had been challenged were upheld, thus putting SSL and the Freethinker on much stabler foundations. (G.W. Foote & Co Ltd, which publishes the Freethinker, was created in 1916 in memory of Foote, and in 1951, SSL acquired it. I myself am still not entirely sure how all this legal stuff works, but apparently it does.)

In the interwar years, the Freethinker carried on, criticising the rise in spiritualism (Arthur Conan Doyle was the target of one such critique, and he penned an angry response to the Freethinker in 1920) and keeping an eye on the rise of fascism and the looming threat of renewed war. In 1936, Cohen responded to an accusation of anti-fascist bias thus:

A correspondent charges us with being “heavily biased against Fascism”. Of course we have a “bias” against Fascism, as we have a bias for or against many other things… A Fascist who is forbidden to listen to the other side, and where Fascism is in power, is punished if he does, strikes us as the last word in human degradation. And we continue to be “heavily biased” against such a system – if “system” is not too dignified a name for it.

I don’t think I need to comment on the relevance of these words today…

During the Second World War, Cohen was pleased that Hitler was finally being challenged, but he was no jingoist, and he criticised Allied propaganda and the British record on imperialism while restating some of the arguments and themes to be found in the Freethinker during the First World War: the rights of nonbelievers in the armed forces and the necessity for utmost free speech even in wartime, for example.

On 10 May 1941, the Freethinker offices, along with the NSS ones, were destroyed by German bombs. The Freethinker was prepared, however, and an emergency issue, which had been kept back for just such an event, was published on 18 May. Cohen, now in his seventies, lamented the loss of paper, stock, and rare books and pamphlets, and admitted that he had sometimes hoped to retire and watch proudly from a distance the continuing successes of the Freethinker and the secularist movement. But he was determined to keep buggering on, as Winston Churchill (who was not, admittedly, very well-liked by the Freethinker) might have put it. On 25 May, Cohen wrote:

And now. Well I have, in a way, to begin all over again. To build almost from the ground upward. But German bombs can no more crush Freethought than British tyranny was able to crush or silence that band of heroic men and women who did so much to build up a heritage and to establish a tradition.

The Freethinker goes on and with it the advanced movement.

I shall now, conscious of time, zoom forward quite a bit. Jim Herrick’s overview must stand in for much of the Freethinker’s post-war history (and, though they were written 40-odd years ago, they could well describe the Freethinker up until the present):

The last quarter of the Freethinker’s history has witnessed considerable changes in format, content and editorship. There are continuous themes such as the remaining power of the churches, a desire for social change, and a moral concern and distaste for all forms of cant. New issues and emphases emerge as the Freethinker responds to the ‘‘new theology”, the growth of cults and superstition, comparative religion, and the challenge of emotional, anti-intellectual, anti-science currents. A less stable editorship and problems of inflation led to many more changes in style and layout than in the previous seventy-five years.

The Freethinker continued much as it always had, championing progressive reforms and internationalism—condemning apartheid in South Africa, arguing for abortion reform, and lamenting the rise of the Islamic Republic of Iran (‘In the fullness of time the realisation must come that a modern people cannot run their affairs on the basis of a medieval penal code or a seventh-century “revelation”’, as one writer put it in 19795)—but before turning to more recent history, I want to look at a couple more examples of prescience and relevance from the twentieth-century Freethinker. In 1960, in response to proposals to outlaw the expression of racism, David Tribe wrote:

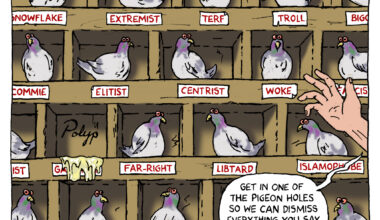

The proposed measure will surely be condemned by liberal opinion as treating Fascism with Fascism. We do not believe that ideas, however foolish or dangerous, can be disposed of by driving them underground. Rather should they be dragged out into the open to be scorched by the pure light of reason. Religious and race dogmatists have a case to put. It is, in our opinion, a false one, indeed a revolting one. But we shall certainly be creating a very dangerous precedent if we deny them the right to put it.

Later in the decade, the Freethinker published an article supportive of Enoch Powell, which caused an uproar among readers. Naturally, and in the spirit of debate and exchange that the Freethinker has always shown, a counter-argument was published (recall Foote’s statement from the first issue about giving space to those who disagreed; this is a tradition that the Freethinker has lived by, even publishing arguments from clergyman—but always with the proviso that a response can be expected, even encouraged). This riposte argued that ‘To allow the racialist a platform is to make him respectable…’ I bring these examples up because of how relevant they are today. Should we allow platforms to the despicable? Is that to sanitise them? Or is it necessary to expose them and uphold the principle of free speech? I am with David Tribe on this, but I find it interesting that these arguments are not really new.6

Now we must really zoom forward. The latest, and perhaps the most radical, change in the Freethinker’s format and publication came in 2014, under Barry Duke’s tenure, when the journal went online only, which it remains to this day. I’m a little sad about this; I’m old-fashioned in preferring physical media. But such are the realities of publishing in journalism today, especially for small independent magazines.

Dr Emma Park took over as editor in 2022, relaunching and revamping the website in its current form, and I took over from her last April after serving as her assistant for a few months. I haven’t made any radical changes; I think Emma brilliantly revived the journal and I simply want to keep up her good work. There have been, as is always the case with these things, some changes in emphasis, however. Emma was deeply interested in, for example, the vexed issue of sex and gender, and commissioned quite a few articles and interviews on it (this was far from her only interest, of course). For Emma as for me, ‘freethought’ is a living tradition, not just a historical phenomenon, and one with a broad remit, beyond just challenging religion, at that.

Having said that, I have perhaps been a bit old-fashioned in that I have returned to a slightly heavier focus on religion, especially Christianity, in the form of the so-called ‘New Theism’, i.e. the resurgence of a politicised Christianity, whose main claim is that religion, Christianity in particular, regardless of whether or not it is true, is the essential ingredient of ‘Western civilisation’ and necessary for its survival. Tom Holland, Jordan Peterson, and Ayaan Hirsi Ali are some of the bigger names associated with this phenomenon. I have commissioned articles and interviews and written at length myself on the New Theism, which I think is only growing in importance and will need to be combatted for some time to come.

For various reasons, but perhaps most pressingly because of Putin’s Orthodox holy war on Ukraine and the theocratic Christianity that is now overtaking America, I think we need to return to that ‘relentless war’ on Christianity. Christianity is still one of the greatest forces of disorder and evil in the world today. Contra the New Theists, I would contend that the defanging of Christianity was one of the great triumphs of ‘Western civilisation’, and that freethinking ideals going back to ancient India and Greece and early modern Europe and beyond are both universal and our only real hope of progress. As I have already quoted Jim Herrick saying in 1982: ‘New issues and emphases emerge as the Freethinker responds to the ‘‘new theology”, the growth of cults and superstition, comparative religion, and the challenge of emotional, anti-intellectual, anti-science currents.’ New theology, New Theism, the recurrent cycles of the religion vs non-religion argument, concerns with Christian/secularist decline/revival… Plus ça change.

In other ways, too, I have sought to keep up some old Freethinker traditions. I have provided space for disagreements to be hashed out (for example, on assisted dying), published a multitude of diametrically opposed perspectives (for example, on the conflict in Israel), and kept Foote’s original offer of debate alive.7

One departure from the past has been an increased willingness to engage directly in political issues. While Foote sought to keep the Freethinker non-political (at least in theory), I have no compunction about publishing, say, a piece trashing Liz Truss. But I think this is simply to widen our range while keeping true to the original ideal of free inquiry and free exchange. And that, I think, is the point: each editor does things in his or her own way, but the caustic, fearless spirit of Foote continues to animate our pages. Emma’s chosen motto, which I have retained, puts it well: ‘Culturally liberal, politically unaligned.’8

Another departure from the earliest days is our attitude to sexuality. Whereas Foote was, like many freethinkers at the time, rather prudish and concerned to show that nonbelievers were not beastly deviants, over time the Freethinker became more open-minded and direct about matters sexual—to the point now where I can publish an article by Peter Tatchell containing the words ‘rimming and bondage’. I haven’t confirmed my hypothesis by searching the archives, but I suspect that article was the first time those words have been used (in a sexual context) in our history (and I suppose this is the second time). Perhaps that says something about me…

We also, of course, continue to be staunch champions of free speech. Indeed, there is an integral link between free thought and free speech, which was well put by Michael Foot in 1981 at the centenary celebration of the Leicester Secular Society’s Secular Hall:

The driving force to save mankind must come from the freethinking tradition, from a tradition that preached internationalism at a time of nationalism. The next century of freethought must be the greatest of all, for the determination to speak freely alone can save us.

For me at least, this commitment to free thought and free speech is one of the two most important and enduring themes in the Freethinker’s history. The other is internationalism, from the early interest in Indian freethought to Emma’s interview of a Ukrainian citizen of Kyiv near the beginning of the war in 2022 and my publication of an exclusive account by Mubarak Bala about his imprisonment for blasphemy in Nigeria.9 For a small, independent journal, the Freethinker has real range, geographically as well as content-wise. And though today we can’t keep up the same quantity of articles as in previous years, I think we make up for it with the quality, depth, and interest of what we publish. We do provide a unique perspective on the world, and we cover stories and arguments that few others bother to.

Despite many changes in format and publication, the Freethinker has endured—surviving the impositions of government agents, pressures to conform to popular lines, world wars, Nazi bombs, financial precariousness, and the transition to the digital age—to become one of the world’s oldest surviving freethought magazines. Not bad going, and one wonders what Foote would make of it all.

With that brief survey of the Freethinker over with, and as promised, on to my Dundonian Addendum. I hope this little jaunt through the archives will be of interest.

A Dundonian Addendum

One of the earliest references to Dundee I could find was in the 22 May 1892 issue, when Foote made fun of the Rev. John McNeill, a popular travelling preacher who had recently been in the city: ‘The Rev. John McNeill has been doing a little of his well-paid free-and-easy business at Dundee. In one of his addresses, John compared himself with his Savior, who went about sometimes in an ill-smelling fishing boat, while John rides first-class.’

There was much more in this scathing vein about McNeill’s lavish proselytization tour (his luxury was provided for by an annual £1,200 grant funded by a chemical works owner). There soon follows a couple of accounts detailing a talk given by Foote in Dundee entitled ‘Why I am an Atheist’ which, we are told, inspired some in the audience to go about setting up a Dundee branch of the NSS: ‘There are a great many Freethinkers in the third city of Scotland, who won’t be converted by John McNeill’s preaching. We have good hopes of the new Dundee branch.’

These hopes were soon fulfilled, it seems: in March 1894, the Freethinker reported that ‘Mr. Foote’s lectures at Dundee have brought the Branch several new members.’ More details were given in the same issue:

The Dundee Branch is in a flourishing and progressive condition, largely owing to the zeal of the secretary, Mr. Gloak. Mr. Foote’s two meetings in the city were appreciative and enthusiastic. On the first evening there was a little discussion, on the second evening none, although a Unitarian minister (the Rev. Mr. Williamson) was present. Invitations, with tickets, had been sent out to thirteen clericals, but only one came, and he belonged to a heterodox denomination. There was a good sale of literature, and the lectures should promote the circulation of the Freethinker. The Dundee friends are full of the approaching debate between Mr. [Charles] Watts and the Rev. David Macrae. It is expected to take place in May, and is sure to stimulate the cause of Freethought.

An April 1894 issue notes that ‘The Dundee Branch continues to make progress’ and informs readers that Watts will be lecturing in Dundee on the 29th of that month and that his debate with the heterodox cleric Macrae will take place on 17 and 18 May.

The 20 May 1894 issue tells us that Watts represented the Dundee Branch at the NSS’s national conference, held on 13 May, and enthuses that

The Dundee Branch has made surprising progress in a short space of time, and is looking forward with great expectations to the public debate which is to take place shortly between Mr. Charles Watts and the Rev. David Macrae, who is one of the most eloquent, popular, and influential ministers in that city.

In the same issue, an interesting piece of correspondence is described:

J.C. McCORQUODALE, 14 New Inn Entry, Dundee, will be pleased to hear from young Freethinkers who will discuss Freethought subjects by correspondence. He proposes that each shall choose a subject, write upon it, and send it round to the rest for their opinions; and thinks the scheme would develop the talents of young members.—“The Gaberlunzie Man” will appear.

‘Gaberlunzie’ is an old Scots word for a licenced beggar which has appeared in various works of literature, e.g. in Walter Scott. In the sixteenth century, James V apparently disguised himself as one and went around singing ballads for room and board. ‘The Gaberlunzieman’ is also another name for the traditional Scottish folk ballad ‘The Jolly Beggar’, which is sometimes said to be about James V’s adventures in beggary. So does McCorquodale mean to say that the song will be sung at some meeting of the correspondents, or is there another meaning I have missed?

On 27 May 1894, the following report of the Watts-Macrae debate is given:

Mr. Watts’s debate at Dundee last week with the Rev. David Macrae was most successful. The rev. gentleman, in his manner of conducting a controversy, was a pleasing contrast to many Christian would-be debaters. The local press gave brief reports, and stated, we see, that the building was “packed to the door” by an “interested and intelligent audience.” We shall publish shortly, in these columns, an account of the debate.

…

The Rev. David Macrae does not appear to have been satisfied with the debate. On the following Sunday evening he referred to it at length in a sermon on “Secularism.” While admitting that Mr. Watts’s speeches were “eloquent and clever,” he said that they were “more conspicuous for their extraordinary and almost ludicrous travesty of the Bible and the teaching of Christ than for a presentation of the true principles of Secularism.” Such a statement does the speaker no credit. It is very bad form for one disputant to give his opinion of the other. The public should be left to decide the matter, as it will in any case.

On 10 June 1894, our old friend McCorquodale gave a long and detailed account of the debate, which opened with an entirely coincidental echo of my own opening tonight:

The land of the Forbes Mackenzie Act [I.e. Scottish Conservative and temperance reformer William Forbes Mackenzie’s Licencing (Scotland) 1853 Act, which, among other things, forced pubs to close on Sundays and at 10 pm the rest of the week] and the kail pot has wakened up of late, especially that part of it familiarly known as Jutedom or Marmalade Town, but geographically designated Dundee. The sons and daughters of that city who attended the Watts-Macrae debate in the City Assembly Rooms on Thursday and Friday, May 17 and 18, showed that they, at least, had got one eye opened, and some of them had both eyelids up.

McCorquodale’s account was fairly even-handed, concluding that ‘The general feeling among all alike was that the Secular arguments were decidedly the stronger, and some disappointment was expressed that the champion of Christianity had offered so palpably weak a case.’ A postscript to this little tale: the Freethinker of 23 December 1894 reported that ‘The Glasgow U.P. [United Presbyterian] Presbytery has prohibited all ministers of its body from inviting the Rev. David Macrae, of Dundee, to their pulpits. Mr. Macrae’s offence is his failure to believe that God will fry his children for ever in hell fire.’

That same issue, incidentally, also contains a response by Charles Watts to a Dundee lecture by the Rev. Alfred Gardner decrying secularism. Taking on Gardner’s charge that secularists are as they are due to ignorance of Christianity, Watts invites the good reverend to ‘put it to the test by examining, say, twelve members of the Dundee Branch of the National Secular Society as to their acquaintance with the teachings of Christianity. Should he do this, we venture to affirm that he will discover that their ignorance upon the subject will be an unknown quantity.’

In October 1896, the Freethinker informs us of the latest on Watts, who, after so much time spent in the archives in his company, is starting to feel like an old friend of mine:

On Wednesday and Thursday, September 30 and October 1, Mr. Watts lectured in Dundee. He had a very hearty reception, and the audiences were the largest he has had there for some time. A good audience mustered the first evening, and on the second the large Victoria Hall was filled. Previous to the second lecture Mr. Watts publicly named Agnes Brown Bricknall, a sweetly pretty baby, three weeks old. Such a ceremony was quite a novelty in Dundee, and all present were much interested in the proceeding. The Dundee Advertiser, in giving a report of the lecture, said: “The proceedings were inaugurated by an incident of a kind which is said never to have occurred in Dundee before. This was the public naming of a child according to the ceremony of the Secular Society, to the Dundee Branch of which the parents of the child belong.”

This tells us something about the shifting meanings of humanism and secularism over the years. Secularism used to denote a broader, non-religious philosophical life stance. Can you imagine the NSS conducting such ceremonies now? No, that sort of thing is really a humanist monopoly these days. In a 1970 Freethinker article about the divisions, distinctions, disagreements, and occasional discord between several national freethinking organisations, former editor Nigel Sinnott noted that ‘under the influence of Annie Besant in the 1870s the NSS held similar “naming ceremonies” until Bradlaugh put a stop to them.’ Given that the Dundee ceremony was conducted in 1896, it would seem that such ceremonies continued for a time, at least at the local level.

(Incidentally, the conflict between the Freethinker and the British Humanist Association (BHA), now Humanists UK, is something I haven’t gone into here, but it is an interesting part of the history of these movements and the tensions within and between them, tensions which were often class-based. In 1967, the Freethinker criticised the BHA as being full of ‘well-educated middle-class people… [and] narcissistically Intellectual Humanists [who] are disinclined to fraternise with working-class people’.10 The Freethinker’s shifting alignments are attested to by the variety of taglines it has featured over the years: ‘Secular Humanist Monthly’, ‘The Voice of Atheism’, and, currently, as I have mentioned and indicating its broader remit today, ‘Culturally liberal, politically unaligned’. Some of these tensions were discussed by Emma Park in her 2022 interview with Andrew Copson, the current Chief Executive of Humanists UK.)

Indeed, Watts in the aforementioned 1894 article made an interesting distinction:

It is here evident that the rev. gentleman was confounding Secularism as a philosophy with mere Freethought. He ought to have known that there is a marked distinction between the two; for, while the latter represents merely a mental condition, the former contains an ethical system with specified rules for the purpose of regulating human conduct in daily life.

Is Watts’s ‘Secularism’ what we now mean by (organised) humanism? (Or should that be ‘Humanism’?) Is secularism now ‘mere Secularism’? (Or should that be ‘mere secularism’?) If so, what of freethought? (Or should that be ‘Freethought’?) I’ll leave that discussion for another time.

Before taking leave of Watts’s article, I was taken by the relevance of its penultimate paragraph to the New Theism debate and the familiarity of the religion vs. non-religion arguments contained therein (e.g. Watts notes that nonbelievers are generally more knowledgeable about the Bible than Christians themselves). The god/religion argument has been going on for millennia now, and it evolves, but it seems that some themes recur again and again. Maybe this is a cyclical phenomenon: secularists might win for a while, but they have to return to the field whenever religion obnoxiously, and perhaps inevitably, reasserts itself. The New Atheist moment of the 2000s seemed to fade away, but now, with the New Theism, the argument must be taken up once more. This is a forever war—and I confess that I don’t mind it at all.11

Zooming forward in time, there is an intriguing article from November 1960 by one E.G. Macfarlane advocating the Dundee Humanist Group’s plans to found a ‘Humanist Day-School’. What, if anything, came of this proposal, I don’t know. Perhaps someone here does. Macfarlane does note that the Dundee Group’s advert in the local press for a public meeting on the subject ‘only appeared once and it attracted only 40 out of about 200,000 probable readers—which isn’t perhaps very good going.’ Er, no. Such public indifference is perhaps painfully familiar to some of us here. A reflection of Chapman Cohen’s from 1925 comes to mind: ‘Indifference is one of the most deadly enemies the reformer has to fight, and it is one of the best friends to all forms of obscurantism.’

Alas, that slightly dispiriting article was the last substantive piece of Dundoniana (‘Dundeeniana’ just doesn’t sound right) I could find in our pages. There are listings for the Dundee Humanist Group in the back pages of several issues in the early 2010s. Given that my search through the archives was somewhat cursory, and given the limitations of our search tools, I’ve no doubt there is more. You can have a look yourself and see if you can find any intriguing connections.

There is one other thing, though. Last year, I interviewed one of Dundee’s most famous sons, the actor Brian Cox. He gave me some good copy, copy which encourages reflection on a perennial question:

What is the notion of a freethinker? It means a person who thinks freely, without any trammelling of any kind. Their thinking is of a sense of liberation, the liberation of the human spirit (their actions might be a different matter, of course). I’m not a classified ‘freethinker’, but that’s what I would have thought a freethinker is. I rather admire and respect that.

I’ve been thinking about why I’m talking to a freethinking magazine. I think because there is a problem at the moment with the cancel culture that we live under. There’s not a lot of free thinking going around. … Cancel culture is offensive and damaging to the human spirit.

I believe in the human spirit. We don’t understand our own mystery. We try to codify it. ‘Say your prayers and it’ll all get better and then you’ll have something at the end of your life.’ But that’s a mystery, and nobody knows anything about that. All we know about is what we’ve got to deal with now, with our two legs, two arms, and two hands, and a head that can, perhaps, function. I feel quite passionate about that. We should give it the respect it deserves and not fall into these [external, dogmatic belief] systems.

Thus concludes my Dundonian Addendum, and nearly my talk.

***

Before I finish, I’ll just quickly say that you can find our historical archive, subscribe to our newsletter, and give us a donation via our website, freethinker.co.uk. Yes, we have endured, but we are still a small, independent magazine, and we rely on historic funds and the generosity of current readers to survive. If you think we offer something valuable in our—let’s be honest—rather rotten media landscape, please do consider donating. Put starkly, we don’t have very long left without such kindness. All donations and legacies will go to make sure that G.W. Foote & Co Ltd and the Freethinker can keep championing ‘the best of causes’ (as Foote’s friend, the writer George Meredith, once called freethought) long into the future.

Thank you very much for listening and I’m happy to take any questions or hear any comments.

Sources and further reading

Porcus Sapiens (I never got the chance to talk about our famous pig logo, brainchild of Emma Park, but if you’re interested…)

Freethinker Historical Archive

The Freethinker Christmas Specials (Or, Happy Solstice!), by Bob Forder

Is all publicity good publicity? How the first editor of the Freethinker attracted the public’s attention, by Clare Stainthorp

Image of the week: Charles Bradlaugh’s struggle and triumph, by Daniel James Sharp

The Freethinker and early republicanism: from the archive, by Emma Park

On trial for blasphemy: the Freethinker’s first editor and offensive cartoons, by Bob Forder

Image of the week: the first issue of the Freethinker—to mark the opening of our digital archive, by Daniel James Sharp

Books from Bob’s Library #4: The Freethinker—over a century of issues now available as a digital archive, by Bob Forder

Vision and Realism: A Hundred Years of The Freethinker, book by Jim Herrick (1982)

From the archive: ‘A House Divided’, by Nigel Sinnott

Saving Bradlaugh Hall, by Andrew Whitehead

- Jim Herrick was, among other things, editor of the Freethinker between 1977 and 1981. He died in 2023; Bob Forder’s obituary can be read here. ↩︎

- In the interest of saving space, this is a somewhat simplified account of Foote’s legal troubles. More details can be found in the sources listed above.

↩︎ - Note Foote’s reference to the ‘delight of battle’: a militant, through and through. Indeed, he had intentionally sought a confrontation with the law over blasphemy. In 1882 he wrote: ‘No prosecution yet! The Freethinker still goes on “blaspheming”, and nobody tries to put it down… Our souls are in arms and eager for the fray, but the enemy won’t come on.’ No doubt an interesting article could be written on the frequent use of martial language by Foote (and many other freethinkers past and present, myself included).

After writing the preceding paragraph, I came upon another example, this time from Chapman Cohen’s farewell address to the Freethinker in 1951: ‘…although I must now return my sword to its scabbard, I hold a rich store of happy memories in the grand fight with the army of human liberation against ignorance, superstition, and priestcraft.’

And it isn’t just male freethinkers who have employed this aggressive language. Although decrying wanton militancy and urging limited collaboration with the religious, Barbara Smoker, former NSS President, once compared the secularist vs. religious dispute to ‘nations engaged in a cold war’ (between which ‘Diplomatic dialogues are the normal procedure’) and argued that ‘genuine knowledge and understanding of the enemy are far more likely to win battles than is ignorance fed upon one’s own propaganda.’ Of course, and as many would attest, Smoker was a very…singular woman.

↩︎ - Somehow I forgot to mention the Freethinker‘s constant agitation for the disestablishment of the Church of England. This often went along with analysis of the decline in religious observance. In 1951, for example, in response to a report which found a steep decline in church attendance since 1901, the Freethinker wrote: ‘These figures, we submit, constitute an irresistible argument for the immediate Disestablishment and Disendowment of the Established Church, not only upon secularist but upon the most elementary democratic principles.’ This argument has long been a standby among secularists, and we are perhaps closer than ever to attaining its aim. Emma Park’s interview with Paul Scriven, who introduced a disestablishment bill in the House of Lords in 2023, might be of interest.

↩︎ - Are we now witnessing this realisation among the people of Iran? Or, rather, since Iranians have long hated their theocratic rulers and desired a secular democracy to replace them, its attempted realisation in the sense of ‘making it real’? The subject of Iran, and the resistance of Iranians to the Islamic regime, has been a frequent topic in our pages of late. See, for example, our insider account of the ‘Women’s Revolution’ by two Iranian activists, Sadaf Sepiddasht and Rastine Mortad, and Noel Yaxley’s report on the role of music in Iranian dissent.

↩︎ - The Freethinker continued to be a free speech champion, of course, particularly in opposing the blasphemy laws. In the 1970s, for example, it, alongside the NSS and other individuals and organisations, stood up to Mary Whitehouse’s private prosecution against Gay News for publishing a homoerotic poem about Jesus, which led to a suspended sentence and a £500 fine for the editor of that magazine (more information here and here). William McIlroy, on several occasions editor of the Freethinker and one of Gay News‘s staunchest defenders, was himself fined £50 for sending the poem through the post! Funnily, as Herrick reports, ‘A copy of the Freethinker from 1922 was handed to the appeal judges [in the case], because their own records of [a previous blasphemy case against J.W. Gott] were missing.’

↩︎ - Colin McCall, a Freethinker editor in the 1950s and 1960s, aimed ‘to keep the Freethinker independent and non-sectarian; to encourage—though not uncritically—all branches of the secular-humanist movement; to give expression to varied and opposing points of view when they seemed worth considering and were reasonably stated.’ This, particularly the last clause, is perfectly in line with my editorial stance. ↩︎

- However, we are not, and have neither intention nor desire to be, a journal concerned with the day-to-day to and fro of politics. (Even if we did want to take such a path, our less frequent publication of new articles would put us at a serious disadvantage, if not make it impossible. This simply means that we must pick and choose and see what falls into our laps when it comes to political comment. Hopefully, our choices are sage ones. At least they aren’t limited by the news cycle and might, therefore, offer more to posterity.) This much remains true, though I like the outlook of David Tribe (editor for seven months in 1966) that ‘most welcomed the inclusion of current political comment though they did not necessarily agree with particular comments.’ This brings to mind Herrick’s statement in Vision and Realism that ‘The Freethinker has always stood for the rational discussion of taboo subjects—knowing that its readers will expect to encounter articles with which they do not agree.’ (Herrick wrote this in reference to the ‘heated correspondence’ surrounding discussion of paedophilia in the 1960s.)

There is an interesting historical tension between freethought and socialism, incidentally: some see freethought as inherently individualistic and thus incompatible with socialism, and this tension was one of the reasons why Foote and Cohen preferred not to discuss politics in the Freethinker. Why alienate individualistic freethinkers with talk of socialism, or socialist freethinkers with anti-socialism?

Personally, I think the claim that freethought is too individualistic to be compatible with socialism is valid only when applied to certain forms of socialism, those which prevailed, say, in the mid-twentieth century when many Freethinker contributors were making such arguments. Oscar Wilde’s socialism, for example, was of an individualistic, pluralistic, and hedonistic kind: ‘Socialism would relieve us from that sordid necessity of living for others’, as he not-quite-paradoxically put it in The Soul of Man Under Socialism (1891). But that’s by the by.

(For anyone who is interested, pp. 30, 47, and 96-97 of Herrick’s Vision and Realism deal with the Freethinker’s—sometimes, sadly, ignorant, and not just for the time—views on Wilde’s life, art, and homosexuality.)

As it happens, Cohen’s successor as editor, F.A. Ridley (1951-1954), was a prominent socialist and Marxist as well as secularist, contributing frequently to the Socialist Leader. He was, in fact, excommunicated from Trotskyism by Trotsky himself. Too individualistic?

A funny and (still) true comment from the Freethinker at the time of the 1951 General Election, just for the sake of it: ‘A General Election has, as such, little to do with Free thought or, indeed, perhaps with thought of any kind.’

Finally, and also from 1951 (and echoing perennial and ongoing debates among secularists), one contributor lamented that secularist activism had become too narrowly focused on ‘anti-theological criticism’:

This is the more surprising in the mid-twentieth century when our enemies, the churches, are all working overtime as political “pressure groups”…

… The final goal of secular society can, however, only be realised by pursuing and enlarging the goal of democracy which implies that secularist politics consist in supporting everything which tends towards the ultimate goal of a secular society and in opposing everything which hinders its attainment, a conception of politics which, we repeat, will be found frequently to cut right across party alignments.

↩︎ - I feel a certain kindred with F.A. Ridley, third editor of the Freethinker (see footnote 8 above). Per Herrick: ‘Ridley brought to his Freethinker a belief that…freethought should not lose sight of its essentially radical tradition. He also brought a global perspective, writing about Islam, Eastern Europe and Africa.’ Ridley once wrote of ‘the reaction in Church and State’ as evinced in ‘the Islamic theocracy of Pakistan, in Calvinistic South Africa, in the newly-formed State of Israel…’ Today one might say the same and even use some of the same examples. Most troubling of all, perhaps, is the Christian nationalist triumph in America under Donald Trump.

↩︎ - Cohen was an early critic of the word ‘humanist’ as used in its current sense, criticising Julian Huxley for describing himself as a ‘scientific humanist’ in 1951, for example. Herrick notes that, towards the end of Cohen’s tenure as editor of the Freethinker (and President of the NSS), there was a shift towards social issues rather than the old theism-atheism debate:

Such social issues were to become an increasingly important aspect of secularism. At a time when anti-theological arguments meant little to a society whose knowledge of the Bible and Christian dogma was vanishing, and when failure to resolve an individualist or socialist position towards economics prevented a direct political involvement [see footnote 8 above], the National Secular Society and the Freethinker were seeking a new role. The word “Humanism” was gaining currency for a less bible-bashing, more ethically centred version of secularism.

Funnily enough, Cohen’s critique of the word ‘humanist’ included the argument that it was more of a historical term than anything else, echoing Andrew Copson’s statement in Emma Park’s 2022 interview of him that ‘”Freethought” feels to me a historically specific thing. I think of freethinking as being a nineteenth-century phenomenon – a very nineteenth-century word.’ Is that the turning of tables I sense? We in the nonbelieving camp are a fractious lot indeed, but that’s only to be expected, I suppose.

See also Herrick’s Vision and Realism, particularly pp. 120-121, for more analysis of the philosophical and organisational disputes between secularism and humanism. Though, as Herrick notes, emphasis on these divisions can be overdone.

↩︎ - Parts of the preceding few paragraphs are taken from my article on Watts (see introduction).

↩︎

Your email address will not be published. Comments are subject to our Community Guidelines. Required fields are marked *

Donate